As the spring climbing season gets under way, hundreds of mountaineers will be lining up on the slopes of some of the highest mountains in Nepal in the weeks ahead. Most will be treading a familiar path taken by many others before them. In focus will be the summits of peaks such as Annapurna I and Mt Everest, and the many laurels that come alongside getting there.

At around the same time, Anindya Mukherjee will be out and about in a faraway corner of Sikkim. Alongside a small team of trusted companions, he will be looking to explore the pristine Passanram valley, nestled between the peaks of Siniolchu and Simvu.

The Simvu twin peaks, as seen from the south Simvu glacier. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

The Simvu twin peaks, as seen from the south Simvu glacier. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

Few would have heard of this remote region. According to Mukherjee, the last time someone actually managed to get there was back in 1937 during an expedition led by the German mountaineer, Paul Bauer.

“It’s one of those fearsome gorges and until we hit the Passanram glacier, this is going to be a jungle expedition. We will be living in the wild, something that I really enjoy,” says Mukherjee, 51.

Modern-day explorer

The excitement is palpable in his voice, which has a lot to do with the uncertainty of charting a course that few have taken before him. There will be no communication with the outside world and no rescue on hand if things were to go wrong. And there’s no reward in store either, besides recognition from those who understand the true spirit of adventure.

In today’s times of instant gains and gratification, Mukherjee thrives on the delights of the unknown and the joy of discovery while navigating his own path. He belongs to the rare breed of modern-day explorers, whose sole motive, like his predecessors, is to fill out the blanks on the map and soak in the satisfaction of chasing an alluring quest.

View of the Rhamani glacier from Deotoli col, explored by Mukherjee's team in 2011. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

View of the Rhamani glacier from Deotoli col, explored by Mukherjee's team in 2011. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

This is the same hunger that drew explorers from around the world to the Himalayas over a hundred years ago. Over in India, the British even hired local men from the hills or “Pundits”, who would set off disguised as pilgrims on long foot journeys and return with observations that helped understand the lay of the land.

But even after years of exploration and the advent of technology, a few questions persist in these faraway regions. And it is these “problems” that folks like Mukherjee thrive on.

“The joy you experience when you are actually discovering something is unparalleled. The fact that you are adding some significant knowledge to this world of exploration, no matter how small, always adds value to what I do,” he says.

Early days

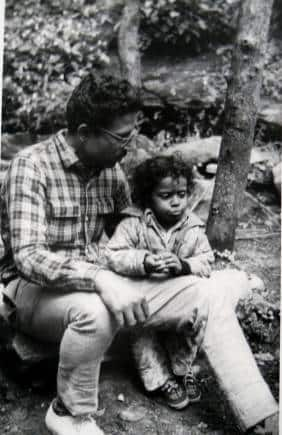

Mukherjee as a child with his uncle, Sujal Mukherjee. (Photo courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

Mukherjee as a child with his uncle, Sujal Mukherjee. (Photo courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

While growing up in Howrah, Mukherjee was smitten by the Himalayas during the annual family holidays. As early as two years, he was bundled off to Gaumukh and Gangotri, and though he doesn’t remember much from that trip, he recalls routinely visiting Sandakphu and going to rock climbing camps in Purulia district by the time he entered his teens.

He would spend hours holed up in the library, where his uncle, Sujal Mukherjee, a first-generation Bengali mountaineer, had stocked up inspirational accounts such as Frank Smythe’s Valley of Flowers (1938) and Thor Heyerdahl’s The Kon-Tiki Expedition (1948), besides the usual Jim Corbett sagas.

The exploits of these men fascinated him and toyed with his imagination. By the time he was in Class VI, he was revelling in his own adventures, whether it was stargazing and birdwatching, or camping and learning how to survive in the outdoors.

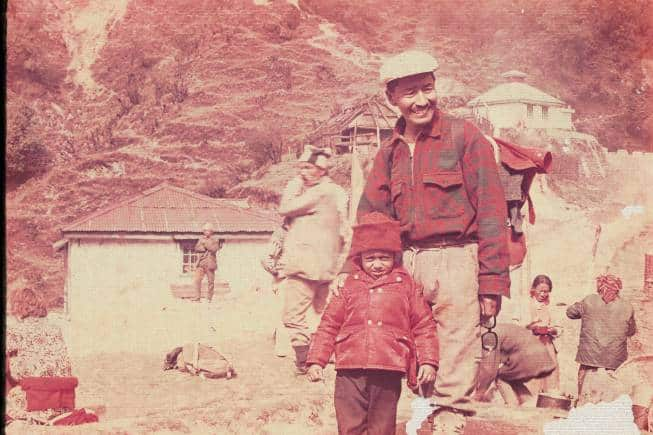

A young Mukherjee with Tenzing Norgay. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

A young Mukherjee with Tenzing Norgay. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

But on graduation, the travails of earning a livelihood sucked Mukherjee right in, and until 2001, he endured the insipid life of a medical representative. All that changed when on an idle weekend, he decided to visit Darjeeling. At the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, he realised the life he wanted to lead. After a quick conference with his father and wife, he decided to chase his calling.

“I often like to forget that chapter in my life because I regret losing so much precious time from my youth, just trying to make money. That just wasn’t me,” he says.

“The trip to Darjeeling made me realise that I wanted to be in the mountains. And the way to do that was to take up guiding assignments in the mountains,” he adds.

Into the unknown

Descending from Zemu Gap icefall. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

Descending from Zemu Gap icefall. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

Over the years, Mukherjee has led a number of commercial treks and climbs. But it was the world of exploration that caught his interest, setting off for uncharted territories to discover new routes or retrace the tracks of others like him in the past.

One of his earliest forays was to the Panpatia Col in the Garhwal Himalaya, which links the Kedarnath and Badrinath temples. Back in 1934, legendary British explorers, Eric Shipton and Bill Tilman, alongside three sherpas had struggled to find a way across and in their footsteps, Mukherjee too made three attempts before finally standing atop the col in 1999.

“Ours was a team of three rookies — a friend and I, alongside a shepherd, Sundar Singh, who today regularly guides on this route. I taught them to wear a crampon during that trek. In fact, I too learnt how to wear a crampon, just a month before setting out,” he says, laughing.

But he continued to build on these experiences and was soon tackling daunting challenges. In 2011, Mukherjee made the first documented ascent of the Zemu Gap from the south. And three years later, he was the first person to set foot on the south Simvu glacier in Sikkim after three previous trips to the area.

Base camp of Zemu Gap expedition, with Pandim North face in the background. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

Base camp of Zemu Gap expedition, with Pandim North face in the background. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

“A real Lost World kind of a thing and something that I really cherish,” he says.

One of the things he’s accepted while attempting these explorations is the high chances of failure. And the fact that suffering will be a part and parcel of the entire experience. He recalls running out of food on one expedition and living off the forest. And getting stranded during inclement weather on another, before beating a hasty retreat.

“You need a certain kind of dedication and passion to become an explorer. Most stick around on known paths because they want to be assured of success. But for me, the problem becomes more interesting when it is difficult and demands introspection before the next attempt. If it could be solved in one go, maybe it’s not even a problem in the first place,” says Mukherjee.

On modest budgets, Mukherjee has set out on international trips as well. On two occasions, he cycled solo and self-supported in Africa, even pedalling 2,000 km across the Sahara Desert over 28 days — his experience has been included as part of the CBSE curriculum today.

Mukherjee in the Western Sahara during his cycling expedition. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

Mukherjee in the Western Sahara during his cycling expedition. (Photos courtesy Anindya Mukherjee)

Then in 2015, he carried out documentation in a remote valley of northwest Yunnan in China, the odds stacked up against him every step of the way.

“The locals there are called Yi Chinese, a very small population. They had never seen a foreigner before. In one village, my interpreter said we had to leave immediately, lest they kill us — they thought I was a drug trafficker. And since I was off the usual tourist circuit, we were even followed by a spy who tried to manipulate my route,” he says.

“It really felt like the early 1900s and is one of my favourite explorations, though I wasn’t exploring a big mountain or a remote valley,” he says.

Close call

In March, Mukherjee and his partner, Lakpa Sherpa, were awarded the Jagdish C Nanavati Award for Excellence in Mountaineering by The Himalayan Club for their exploration of Sunderdhunga Khal in Uttarakhand. Their attempt was to reverse the route that Tilman had taken over this col — the only crossing recorded so far — while exiting the Nanda Devi Sanctuary in 1934.

Lakpa Sherpa and Anindya Mukherjee.

Lakpa Sherpa and Anindya Mukherjee.

On their second attempt, Mukherjee and his partner, Lakpa, seemed to have cracked the problem. After scaling 6,000 ft of what seemed like an impregnable steep section of rock and ice, they had just to negotiate the final trudge up to the col, when a piece of serac whizzed past Mukherjee, missing him by inches. His experience told him it was time to retreat and that night, they heard the entire tower of ice come crashing down, high above them.

“I’ve certainly become more composed over the years and take fewer risks than I used to back in the day. Safety is something that I always keep at the back of my head. But I have to do these crazy things, it’s a compulsion else I feel like I am dying a slow death,” he says.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.