In 2009, Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie spoke about the danger of a single story, which robs people — the excluded ones — of dignity, making their recognition of their equal humanity difficult. In India today, perhaps, more than ever before, popular cinema — an ideological state apparatus — is churning out films on Hindu rulers and mythology. It is a certain pedagogy being steered by popular stars. From Bajirao Mastani (2015) to Chhaava (2025), popular cinema and its omission and commission results in erasure of history in the pursuit of “a single story”, the story of upper-caste Hindus, by avoiding/removing the mentions of Dalits, Adivasis, or Bahujans, let alone making them the protagonists. In 2020, journalist-turned-filmmaker Jyoti Nisha theorised Bahujan Spectatorship, which is a counter to the mainstream representation and ways of looking at the Dalit community. There have been one too many films on the Father of the Nation Mahatma Gandhi, but just how many Hindi films are there on the Father of the Constitution, Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar?

On BR Ambedkar’s 134th birth anniversary, April 14, streaming platform MUBI released two documentaries on the man and his legacy. Jyoti Nisha’s Dr. BR Ambedkar: Now & Then (2023) and Somnath Waghmare’s Chaityabhumi (2024). Much like how Ambedkar established the newspaper Mooknayak because he faced resistance from the existing media, particularly Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Kesari newspaper, filmmakers like Pa Ranjith, Nisha and Waghmare are creating a counterculture to resist Dalit stereotyping in films.

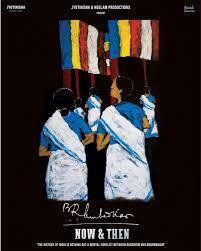

Poster of 'Dr BR Ambedkar: Now and Then'.

Poster of 'Dr BR Ambedkar: Now and Then'.

Nisha’s powerful film, both observational and self-reflexive, is an indictment of ways of seeing and a celebration of a Bahujan feminist gaze. She shows how even the feminist movements lack intersectionality, choosing to focus on just gender, not caste. Nisha’s informative film is replete with inspirational moments. She blends documentary with animation, contemporary history with mythology seen from her gaze. Eklavya sacrificed his thumb for Dronacharya but the blood that spilled spawned future Eklavyas like Rohith Vemula. The award-winning documentary has been co-produced by Tamil director Pa. Ranjith, the founder of anti-caste platform Neelam Cultural Centre, who’s been changing how cinema treats Dalits.

Nisha’s film, which speaks to people from her community, is a personal one. Caste location didn’t allow Nisha’s late mother to get an education. Nisha, 41, worked as a journalist before studying at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and Film and Television Institute of India (FTII). Born in UP’s Hardoi, she grew up seeing her late father Netram Singh, national president of Kanshi Ram’s BAMCEF (The All India Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation), being involved in Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti.

Her film trains the lens on the leaders and foot-soldiers of the anti-caste movement. From powerful Dalit feminist voices like Thenmozhi Soundararajan, who says in the film “For a day Jack Dorsey got to experience what it was like to be a Dalit woman” in reference to him tweeting a photo of himself holding a ‘Smash Brahmanical Patriarchy’ sign, to Raya Sarkar, whose LoSHA (List of Sexual Harassers in Academia) was the start of the Indian #MeToo movement in 2017, but which was called by savarna women a “witch hunt that lacked due process”. From the late Rohit Vemula’s mother Radhika Vemula telling the crowds to raise their children to be like Ambedkar to a female survivor of caste violence in Saharanpur in UP saying, “We will die for him. Babsaheb should not be dishonoured.” And Jignesh Mevani leading a public anti-caste pledge at Una.

In this first of a two-part interview series, Nisha talks about the making of the film, Ambedkar’s continuing relevance and legacy, and Bahujan feminist gaze. Excerpts:

Jyoti Nisha in a still from her film 'Dr BR Ambedkar: Now and Then'.

Jyoti Nisha in a still from her film 'Dr BR Ambedkar: Now and Then'.

What does Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar mean today?

He’s a beacon of progress and scientific temperament. That’s what I have learnt. If you read his writing, there’s some kind of liberation. It’s in Buddhism as well, ātmadīpo bhava, that is ‘be your own light’. So, he’s that person. He is his own light. It’s this one person who has went on adding one skill after another. The grit of this man. And to have committed his life to a cause, generations are incredibly grateful for him for the rest of their lives.

But I think upper-caste people are not grateful for him and that’s why his story has been excluded. The whole history of anti-caste movement has been excluded and appropriated. Even in South Asian studies, where upper-caste people are talking about caste, the representation and the work of the anti-caste movement or women certainly even in the feminist movement has been excluded. So, that exclusion is like a very systemic exclusion that’s been going on for thousands of years. So, I decided to making a film on this because since 2014, a lot was happening in the country. I was also ready to make a film. I was looking for a story. I did not think that I could make a film. I had never made a film before this. But I just felt like this is the really right story to tell. I also felt like nobody is going to tell the story because certainly they have not. Of course, there is Jabbar Patel’s film (the Mammootty-starrer Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, 2000) and there is Jai Bhim Comrade (2011) by Anand Patwardhan. I had a very different imagination and experience of the community. I felt like it really needs to be told in the context of the times that we are in.

Ours (the anti-caste movement) is a continuous assertion. It has ancestral history and cultural movements. It started from Bhakti movement, then it became a social movement and then political movement and now it’s a cultural movement. You cannot hide Dr Ambedkar’s contribution. I feel like the upper-caste people have to embrace it and educate themselves, read him, then they will be liberated also, released from such conditioning where you are also not allowed to do certain things. They will get the sense that this man has made this country. Accept it, know it, talk about it, share it. Like the way we talk about Marx, talk about Dr Ambedkar.

Eklavya's thumb-cutting reimagined in the film.

Eklavya's thumb-cutting reimagined in the film.

You start the film with your voice-over that says ‘the film is not working for me’, you’ve edited the film three times. What approach you wanted to take with the film, how long did that take?

It took eight years to make the film. I started in 2016. So, I had some money, I was working, I had this idea. There was so much happening, Bhim Army movement, Dalit Asmita Yatra, a lot was happening in JNU and FTII. The Hyderabad University student Rohith Vemula was pushed to take his life. I was hearing of stories and I really wanted to document that, so we just started documenting. In 2014, I was at home with my mother and brother and we were talking about Dr Ambedkar, about his contributions, watching WhatsApp videos and I found it really interesting and why nobody has told the story right. So, I felt this seems like something I know, honestly, and this needed to be told as I really felt something monumental was happening which I wanted to document. I’m not a filmmaker, I’ve not even made a 5-minute film. I did raise some funds, post-production funds of Rs 20 lakh with Wishberry, I crowdfunded. And, that’s how I met Pa. Ranjith, my co-producer. Ranjith’s coming has increased the potential of the film.

The first edit of the film, in 2021, was not working for me. It was very tight and very heavy since a lot was going on. I felt it needed some breathing space. I worked on the rhythm and the pace. In 2020, I had theorised Bahujan Spectatorship and I wanted that to be part of the film because it’s from that framework that I’m actually looking at. My editors then said, ‘why are you not there in the film? You are aware about this and speak so well.’ I was very camera shy but I did it.

In your film, Gujarat MLA Jignesh Mevani says the Dalit movement is stuck in identity politics instead of talking about the issues of land rights, education and employment. Your thoughts on that?

No, I mean, surely, I will talk about representation because this is my space. I am not talking about land rights. Jignesh Mevani can talk about it because he’s a politician. He must talk about it also. What he’s saying is true also. So, for all of us, the goal is the same: to uplift the community, to have upward mobility, to progress, to educate. There are still villages in our country that are really backward in terms of infrastructure, not backward in terms of the talent that exists there. I just went to my cousin’s wedding in the north in Dhampur in Uttar Pradesh and there are students who are pursuing BSc., MSc., Masters. They want to be a teacher or journalist or doctor. But you have to see the infrastructure of that village. It’s the work of the state which has to develop these communities. So, again, the goal is the same.

See, the stories of people who are doing the work needs to be told, that’s why you have a Mahatma Gandhi road everywhere in this country. But how many roads do you have in the name of women leaders or Muslim leaders? You have to see that balance. I think the symbolism and this leadership needs to be celebrated more on the screen because it’s the story of our cultural movement. It (cinema/web-series) has the largest impact on humanity or human experience. It has a pedagogy also to teach and look at people in a certain image and a certain gaze with a certain kind of way of looking and putting them in a certain kind of cultural context and a probably stereotype. Especially rape, for example, when you see gang rapes of people or violence, as a woman, I do not enjoy that kind of violence or criminal web-series or television or films, because then I really also think very logically as a woman, I’m not having a great experience watching this because it’s just so sensational and traumatic, at the same time, there is a generation who’s watching it and who’d think that you can do that to women or women of a certain community. I think that kind of accountability is also very, very important, because cinema has a pedagogy, it is about the popular culture and is very, very powerful.

In a still from the film, Radhika Vemula (centre) is seen leading a peaceful protest march in the memory of her late son Rohith Vemula in Hyderabad.

In a still from the film, Radhika Vemula (centre) is seen leading a peaceful protest march in the memory of her late son Rohith Vemula in Hyderabad.

Dalit women have been, perhaps, the most invisibilised in our popular culture. Your film opens with activist-policy researcher Cynthia Stephen who speaks about Dalit patriarchy. Does Dalit patriarchy operate in the same modality as Brahminical patriarchy?

See, I don’t know how to segregate the two because the root is the same actually. That you are at the fourth varna of the caste system and women, Shudras and Ati-Shudras are all there, you may have material access and riches but autonomy and your rights are really curtailed. I look at it like that. But I think in our community, what I have seen is that men are slightly still more flexible, they are kinder and they hang out with women and do the work at home as well. I would speak about my Mama (maternal uncle), he does everything at home. And there is certain kind of a camaraderie which is there, which is very interesting that we do not see that in city but you see that in the village, that autonomy, that helping each other out, whether it’s doing something in the kitchen or lighting a beedi for her or hanging out in the evenings or dancing together on their son’s wedding. The men are also the victim of the same Brahminical patriarchy. So, they are aware of the existence of the kind of hatred towards women from a certain kind of caste. The collective shared struggle makes it (patriarchal oppression) a little lesser, which exist strictly in Brahminical spaces, like, for example, during menstruation, I was not an untouchable in my house, I could sleep anywhere, I could eat anything, achaar or whatever. I had conversations about periods with my brother. But I have also seen very, very worse forms of it where women are not allowed to have friends. Like I have had friends from the community where boys were absolutely not allowed to make friends.

As a filmmaker who’s grown up watching popular Indian cinema, has there been any character or film that has somewhat done justice to the Dalit representation on screen and you could relate to?

I mean, as a woman, I think Natchathiram Nagargiradhu (2022) by Pa. Ranjith, the character of Rene (Dushara Vijayan), I really connected with her. She’s bold, she says assertively that she’s an Ambedkarite. So, yeah, that film.

You’ve assisted Neeraj Ghaywan on Geeli Pucchi (Ajeeb Daastaans, 2021). He’s headed to Cannes Film Festival this year with his second film Homebound. As a Dalit filmmaker, how do you see screen representations of the community being essayed by non-Dalit actors?

It will be an ideal situation if that happens (a Dalit person playing a Dalit character). I was working as his director’s assistant, in both creative and production departments. I did read the scripts a bunch of times and gave my feedback, especially during the pre-production, when you’re reading the script with all the heads of the departments. I’m a screenwriter, I understand characters. I had to get those references of the production, like how the house of Bharti Mondal (essayed by Konkona Sensharma) would look like, what colours would she wear, or how the house of Priya Sharma (Aditi Rao Hydari) would look like. Since I am from Lucknow, I also did dialect exercises with both the actors but mostly with Konkona. The script was based in Kanpur, so I got references from Kanpur, gave the description of the character, of a single woman who identifies as Dalit queer.

I felt I was very strong on research, I had already theorised Bahujan Spectatorship and there’s some history of anti-caste movement in my family. I have studied MA in media and culture studies and studied caste and gender, so those critical arguments and the understanding of the anti-caste movement was very much there to have that assertive gaze. And Neeraj was very much aware about it that we wanted a character who’s assertive and he gave Yashica Dutt’s Coming Out as Dalit: A Memoir (2019) to Konkona. I mean, nobody could have done the job better than a woman from the community who was on the set and having these conversations with the actors. Understanding that the agency of a Dalit woman whose ancestry comes from a family of midwives. This is very different from Priya Sharma, at least I saw these characters like that. So, I did give those feedbacks. You can clearly see the kind of research that has happened and why the film hits differently because it really is about representation and having that experience.

With regard to the current controversy around the Pratik Gandhi-starrer film Phule, the CBFC’s demand for removing the terms Mahar, Mang, Peshwai, and Manu’s system of caste — ironic because caste discrimination is what Phule had fought against in life — in such an atmosphere, how do you produce films truthfully?

It’s not so much about how the filmmakers are saying what at what time, it’s completely their ideological, intentional and aesthetical choices to tell the stories what they want to tell. The control is more to do with the State. What stories it allows to be told and who is telling those stories and whether they stand against what is predominantly practised in the country. The bigger question is whether people are standing together for the freedom of expression. It’s so important to have this conversation because otherwise we would not have a progressive society that we want. And stories need to be told. You cannot hide the truth. It may take a little bit of time for sure, but I think as a community, as citizens of the country, it’s really important to stand by the right thing.

A still from the film.

A still from the film.

In a post-truth world, how do you keep pushing back as an artist?

It’s something you live with, right. It’s almost like you want me to not have self-respect or integrity. You have to preserve yourself when the onslaught of the State is so evident in your life. I also question what kind of filmmaker I am and I understand how the networks work in the film industry, because it’s extremely recommendation-based. But how would you really stop the right conversation? I really think that the role of the audience is so critical to bringing any kind of change. Whether they are students or artists, they must continue to question. Now, caste is being talked about in cinema or films on caste are starting to get made. It’s a new phenomenon, as far as I think, from an assertive gaze.

Until now, caste has been extrapolated as class, as a class perspective, from a Marxist perspective, but from a perspective of Dr Ambedkar’s ideology on aesthetics or Phule’s ideology, it’s a different iconography that’s happening at this point of time. It’s a different kind of oppositional consciousness that exists at this different point in time, where you have Chandrasekhar Azad or Jignesh Mevani or filmmakers and artist movements. It’s a continuous process and it’s really about people’s movement. It cannot work without people and people of all class and caste and experience must have that conversation.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.