Anti-caste publisher S Anand started out as a journalist in Chennai in the late 1990s. During this time he read BR Ambedkar’s writings that transformed him. “I read 12 heavy volumes of Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches in 1999. I’d ordered them via the now-obsolete VPP (Value Payable Post) from Blumoon Books in Delhi,” says Delhi-based Anand, 52.

Between 2001 and 2007, he worked as a reporter at a national news magazine. “In these years, I drew close to the anti-caste movements in Chennai and other parts of Tamil Nadu. Editors at the Tamil monthly Dalit Murasu became my comrades. Ravikumar [currently a parliamentarian], an independent intellectual-activist from Pondicherry, suggested the idea of a publishing house. With four titles and our modest savings, Navayana was born in 2003, when Ravi and I decided to address the fact that there was almost nothing in English language trade publishing that took on caste and carried forward Ambedkar’s legacy,” says Anand. In 2007, Anand moved to Delhi after he won the British Council-London Book Fair’s International Young Publisher of the Year award. He says, anti-caste publishers like “(Yogesh Maitreya’s) Panther’s Paw and The Shared Mirror, which published a severe critique of Navayana, are great initiatives and we need more from them and many more of them.”

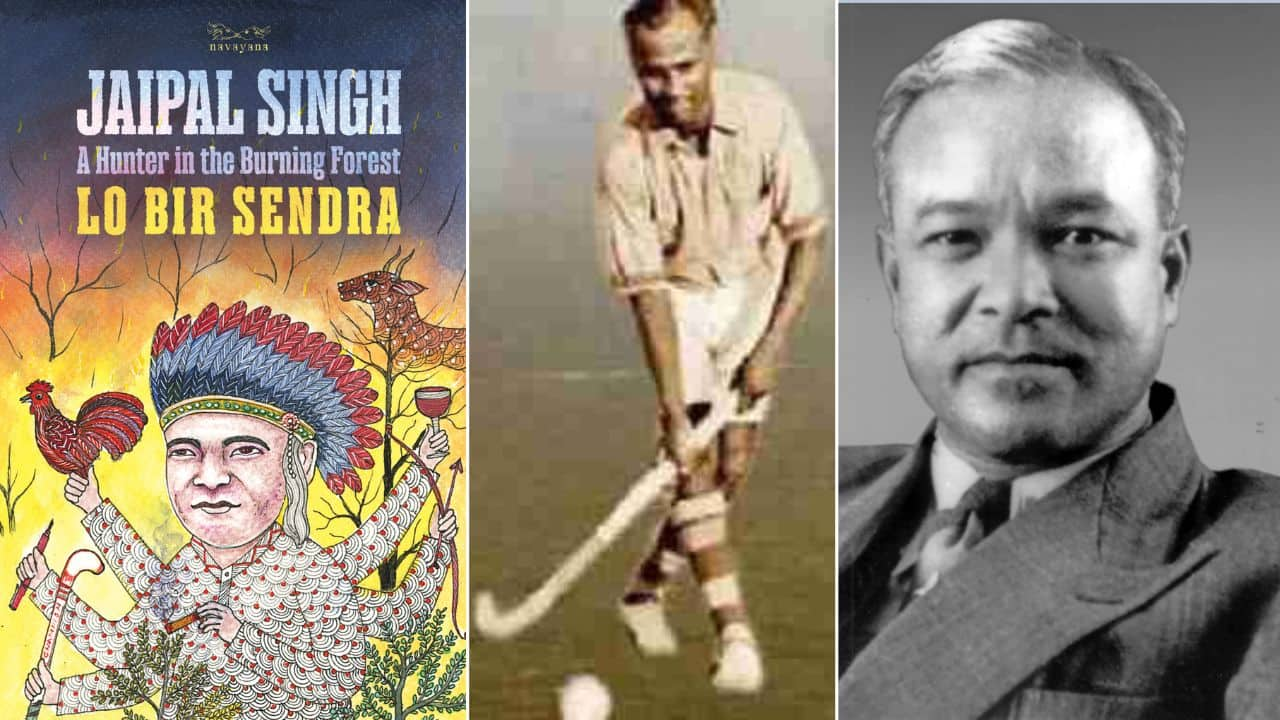

Anand, also a poet and musician, recently published The Notbook of Kabir: Thinner than Water, Fiercer than Fire (Penguin Random House, 2024), and as publisher at Navayana he brought out a refurbished reprint of the memoir of the little-known great Adivasi leader Jaipal Singh Munda, Lo Bir Sendra: A Hunter in the Burning Forest (2025). Munda was an Oxford scholar and Olympic hockey champion and a member of the Constituent Assembly, and left this memoir, written in 1969 during a sea voyage, with an Italian scholar. Anand managed to trace this handwritten script and re-issued the book.

Excerpts from an interview:

Jacket of a new reprint by Navayana of the memoir of Adivasi leader Jaipal Singh Munda; portraits of Jaipal Singh Munda as a politician (right) and as a sportsman.Tell us about finding Jaipal Singh Munda’s memoir. Why is so little known about the most influential Adivasi leader since Birsa Munda?

Jacket of a new reprint by Navayana of the memoir of Adivasi leader Jaipal Singh Munda; portraits of Jaipal Singh Munda as a politician (right) and as a sportsman.Tell us about finding Jaipal Singh Munda’s memoir. Why is so little known about the most influential Adivasi leader since Birsa Munda?Stan Swamy (the late tribal rights activist) was the first to publish this work with lawyer Rashmi Katyayan’s help in 2004 in Ranchi. It was soon lost to time. It was an amateur edition with several errors. Before we published, we got a copy of the original handwritten manuscript of 1969 through Italian scholar Barabara Verardo. Then we embellished it with annotative notes, weeded out errors, and added 30 archival photographs and a map. That we know so little of an intellectual and political giant like Jaipal Singh — who was an Oxford Blue scholar, Olympic hockey champion and pioneering politician (prominent member of the Indian Constituent Assembly, elected in 1946) — speaks volumes of the kind of society we are.

Was Navayana started to bring Dalit literature to the non-Dalit reader or bring resistance literature to the Dalit reader?The only kind of Dalit writings we saw in English back then were translations of autobiographies. Poisoned Bread, an anthology of Marathi Dalit writings edited by Arjun Dangle in 1992, published soon after Ambedkar’s birth centenary, was the first modern Dalit book issued by a mainstream publisher. This was followed by a trickle of Dalit memoirs in translation from Marathi, Kannada and Tamil. My friend Ravikumar questioned this prioritisation of the autobiographical mode, where recollection of pain and humiliation invoking Savarna concern and orthodox pity became the norm. Back then, in 2001, when the World Conference Against Racism was unfolding in Durban, most Indian intellectuals said the issue of caste, and the very real apartheid Dalits faced in India, cannot be raised internationally or compared with racism. It was a time when even public intellectuals like Arundhati Roy stayed aloof and had little or no idea of Ambedkar. Navayana wanted to redress this lack.

Yes, publishing in English, meant our primary readership was likely Savarna, too. Most Savarnas, even today, have little or no idea of Dalit lives save for what little they read. Most urban Savarnas tend to think of Dalits as ‘quota people’. The liberals merely appear civil. In terms of civic interactions, what Ambedkar calls social endosmosis, even today Savarnas rarely socialise with Dalits as equals. At best, Savarnas interact with Dalits-as-menials and often say caste is not an issue for them at all. Navayana wished to challenge if not change this discourse.

Could you briefly throw light on the evolutionary history of Dalit literature?As long as there’s been injustice in the name of caste, there has also been the cry for justice. Chokhamela in 14th century Solapur, western India, was a pioneer of sorts. In spite of Ambedkar moving away from the Bhakti framework, he dedicated a book to Chokhamela. Charyapada, a 12th century Bangla anthology of ‘mystical’ poetry, inspired by Vajrayana Buddhism and Tantra, is mostly written by Dalits. Much of the Kabir singing we know comes to us via Dalit-Bahujan oral traditions. So also with Buddhist ideas, as I have tried to show in my own book The Notbook of Kabir. Let us remember that the Buddha was the first cult figure who was a subject of mass adoration and adulation, or simply bhakti. The other Hindu gods and goddesses get shapes, forms and poetry much later. What’s often passed off as Bhakti across India has a range of Dalit voices severely critical of caste. Ambedkar was the first Dalit author I consciously read.

Statistically, less than 30 per cent of Navayana’s writers are Dalit. This could, perhaps, make us feel better than other publishers, but the truth is even at Navayana the balance is lopsided. In 2014, when we published the annotated critical edition of Ambedkar’s classic, Annihilation of Caste, with Arundhati Roy’s introduction, we were pilloried. Questions were asked: ‘Why Roy? This is brazen appropriation. Why are so many non-Dalits writing for Navayana?’

Kancha Ilaiah to Gail Omvedt were passionate anti-caste intellectuals but not born Dalits. Almost 40 per cent of our books revolve around Ambedkar, with him either as author or the subject. But in terms of living Dalit authors, even Navayana falls short. When we published Namdeo Dhasal’s poetry in 2007, it was translated by Dilip Chitre, a Savarna. When we published Ajay Navaria’s short fiction in 2013, Laura Brueck, a white American, did it. Bhanwar Meghwanshi’s memoir Why I Could Not Be Hindu: The Story of a Dalit in the RSS (2020) was translated from Hindi by the renowned feminist Nivedita Menon, a non-Dalit. We do not accept or reject something based on an author’s caste. But surely, we are biased in favour of Dalit writers. Years of Savarna indifference to the caste question, and the lack of access to resources like English among the few Dalits who can avail of reservation, has left us with a situation where even at Navayana, we have more non-Dalit writers than Dalits; and almost no Dalits who are translators. This is indeed a sorry state of affairs.

In 2021, to make amends, we announced the Navayana Dalit History Fellowship — open only to Dalits. This meant nurturing and handholding new writers. Again, this is not easy — especially since universities which are meant to instil and curate these processes are often openly hostile to Dalit students. The killing of Rohith Vemula’s body and spirit stands testimony to that cruelty. And private illiberal places like Ashoka University have no place for Dalits or Shudras. These are quota-free havens of inequality as is most of mainstream media and publishing. The severe lack of Dalit writers or translators is a larger social and systemic issue, and Navayana is caught in this ecosystem.

You are a Savarna, not Dalit. Did a guilt complex about your caste privilege propel you towards your anti-caste sensibilities?It was my misfortune to be born and raised in a Tamil Brahmin household in Hyderabad. For me, my mother being cast out of the kitchen and having to huddle by the bathroom for four days while menstruating was the first case of internal untouchability that I witnessed. For my parents and family, anyone not a Brahmin was an Untouchable. It was not guilt but anger that made me work my way away from this world. Falling in love with a non-Brahmin and having to break away from my family was a teaching moment. I learnt that caste and love or maithri (friendship) are incompatible. Soon, my intuitive dislike of caste found an edge when I discovered Periyar, Phule, Ambedkar and other voices, both Dalit and non-Dalit. Navayana, I reiterate, has never called itself a Dalit publication. Lazy Savarnas tend to tag this label on us. I align with many thinkers who thought against inequality — Buddha to Marx and Ambedkar. I hope to pass on the Navayana legacy into more capable hands.

Jacket of the book 'The Notbook of Kabir' by S Anand, published by Penguin Random House.Is your book The Notbook of Kabir the first such to bring casteless Kabir and anti-caste Ambedkar on the same page?

Jacket of the book 'The Notbook of Kabir' by S Anand, published by Penguin Random House.Is your book The Notbook of Kabir the first such to bring casteless Kabir and anti-caste Ambedkar on the same page?Perhaps it is. But I’m not making any such claim. As someone working for over two decades with Ambedkar’s life and writings, I went to Kabir and the Buddha through the prism of his ideas. There surely have been many Dalit voices who’ve seen Kabir as an anti-caste poet. The fact that many of the renowned so-called ‘folk’ singers of Kabir — Kaluram Bamaniya, Mahesha Ram, Prahlad Tipaniya and Mukhtiyar Ali — are Dalit, tells us that story anyway. The sad reality is this: For generations, liberal Savarna writers and thinkers in India — from A.K. Ramanujan to A.K. Mehrotra — did not engage with Ambedkar. Even scholar–translators like Linda Hess have engaged with the caste question in Kabir only belatedly. Most mainstream efforts at engaging with Kabir or such voices came without this basic understanding, and hence, they came to see Kabir as an embodiment of bhakti and the wisdom of the Upanishads. With The Notbook..., I have merely prised open a window. There’s so much more to be explored.

What elicited your aversion to the Bhakti tradition? According to your book, Kabir was tamed under it and Ambedkar was displeased with Dalit Bhakti poets.In India, we foist big labels. Hinduism is one such — it is a way of covering up the issue of the thousands of castes and differences we have. Bhakti was and is similarly propped as a category into which you could group all those poets who challenged inequality. Like Chokhamela, these poets often faced severe blows to their body and spirit. Chokhamela’s intense bhakti for Vitthal did not lead to any social acceptance. He was brutally attacked for trying to enter the temple. There are several unsung abhangs where Chokhamela rebukes god, and trashes the Vedas and Shastras. The best poetry in this land has often been written by Dalits and women, often from a place of lack. Go back to the Therigatha (anthology of poems by and about the first Buddhist women), if you must. Yet, several of these protesting voices which laid claim to the divine and even the temple, were booted out. Some like Chokhamela and Ravidas were murdered, according to Dalit retellings. Ambedkar comes to reject the very idea of god and even the existence of a soul, like the Buddha did before him. Ambedkar saw through this and wanted a fresh start and said, let’s demolish this house and build a new one.

You learnt Carnatic/Hindustani classical music and gave it up for Kabir songs, but the two can co-exist, as the Brahmin Kumar Gandharva has shown.I gave up Carnatic music at the age of 25, having learnt it for seven years. Its inherent and incurable Brahminism made me quit. I returned to singing because of Kabir in 2013–14, and The Notbook... evolved over 10 years. I continue to train in the rather abstract alaap-driven mode of Dhrupad — where Buddha’s and Kabir’s ideas of nirgun (formlessness/ essencelessness) are best expressed without words. Not just Kumar Gandharva, the entire bhakti industry has a need for Kabir and scores of such poets across languages. Gandharva was a contemporary of Babasaheb Ambedkar and lived his early life in Mumbai — and yet had no engagement with the caste question. The fact is, most Savarnas did this and continue to do this. The Dalit Panther (movement) flourished in Maharashtra during the 1970s when Gandharva was singing his Kabir, Tukaram and Chokhamela. What was his social or aesthetic engagement with their critiques? Nothing. Or think of how the so-called ‘progressive artists’ of Mumbai shunned the caste question and Ambedkar. Second, what we have come to call Hindustani music is itself a misnomer. It makes it sound like the music of the Hindus. I prefer the term raga music. In the north, the framework of raga music came to be inflected by Arabic and Persian influences. By the 19th century, raga music was predominantly performed by Muslims and women who were Bai or former devadasis, belonging to the ‘Nat’ community, which is mostly Dalit-Bahujan communities. Like we saw with the shuddhi movement led by Arya Samaj and others, where Brahamnic Hinduism was purged of foreign influences and made shuddh, so also in music Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande and others undertook this shuddhikaran (purification) to purge it of Islamic influences. Kumar Gandharva was trained in and fell prey to this logic. Katherine Schofield’s recent book, Music and Musicians in Late Mughal India: Histories of the Ephemeral, 1748–1858, gives you a completely fresh and different story of what happened to music. The short answer is, Hindustani music is inherently not at all Brahmanical like Carnatic, which resolutely became so after the 18th century.

What do you make of T.M. Krishna’s critique of Brahminism of the Carnatic world?His is a minor and mild reformist critique of the existing culture. Given how deeply conservative Carnatic music is, his posturing appears radical, bringing in new audiences to a jaded, insular genre. He continues to sing an ultra-Brahmanic repertoire of songs — by Thyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar and Syama Sastri. He divides and rules — singing [Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s] Hum dekhenge at Shaheen Bagh and Dikshitar’s Sanskrit stuff for the pontiffs of the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham. His acceptance of the Sangita Kalanidhi, given invariably to Brahmins, is ghar-wapsi. Ambedkar sums this up best in Annihilation of Caste: ‘There can be a better or a worse Hindu. But a good Hindu there cannot be.’

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.