Somnath Waghmare’s documentary Chaityabhumi (2024) opens in Rajgruha, the house in Mumbai’s Dadar neighbourhood where Bhim Rao Ambedkar lived. Things at the house seem to be frozen in time, from his wicker chairs and work desk to his bathtub and the bed on which he lay in his last moments. Photographs of various historical moments Ambedkar was a part of adorn the walls. The film then reaches Chaityabhumi, close by, where stands the white-domed seaside memorial on the site at which BR Ambedkar was cremated in 1956. The place is teeming with crowds, who have come from all over the country, including members of political groups, folk performers and Buddhist monks. There are stalls selling Ambedkar’s books, calendars and statuettes of the great leader and the Buddha. We hear Babasaheb’s great-grandson Sujat Ambedkar speak. Tying up the film’s sentiments in a thread are the protest songs performed at Chaityabhumi by Dalit artists.

For Maharashtra’s Ambedkarite families, visiting commemorative sites such as Chaityabhoomi in Mumbai, Bhima Koregaon near Pune, Deekshabhoomi in Nagpur — which is “a very vibrant place where the Ambedkarite movement is there in everyday life,” says a scholar in the film — are a part of their cultural life. The 106-minute-long Chaityabhumi — which released on MUBI on the 134th Ambedkar Jayanti, April 14, in the Dalit History Month — is a film essay on the annual Ambedkar remembrance pilgrimage to the eponymous place on Ambedkar’s death anniversary, December 6. It is presented by Tamil director Pa. Ranjith’s Neelam Productions.

In the second of an exclusive two-part interview, Somnath Waghmare talks about his films, Maharashtra’s history of some dominant-caste people having been anti-caste, Bollywood’s saviour complex, and more. Excerpts:

Tell us a little about yourself and your family.

I have been living in Mumbai for the last five years. I did my MPhil from Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) on Marathi cinema, on how people are using cinema to dominate their caste culture. I’m in the submission stage of my PhD.

My family stays in a village called Malewadi, in Maharashtra’s Sangli district, it’s near to Kolhapur. Interestingly, my father was a mill worker in Mumbai and we used to have one small house in Ghatkopar slum. In the ’90s, when mills were shut down, my father shifted to the village and both my parents started working there. I grew up there, in a caste ghetto. I was still in the village till my graduation. Then I shifted to Pune University for my master’s in a media and communication. Then, I realised that whatever my life is that is completely missing on cinematic space. So, that pushed me to start filmmaking.

Caste in village is a little bit harder than a city. Another interesting thing is that in a city, the population of the movement of the Dalit people is a huge. Discrimination is there, but the form is different. But in a village, if you visit any Maharashtrian village, there is like a caste ghetto. And everybody knows everybody. Caste is very prominent in Indian villages.

What was your vision with Chaityabhumi and what was a must-have in the film?

Actually, before Chaityabhumi, I’d started working on the biopic of Gail Omvedt, the American sociologist and Ambedkarite scholar who came to India and wrote extensively on Dalit movements. So, after Ambedkar, there are three-four scholars, especially those who wrote in English, Gail Omvedt, Eleanor Zelliot, Kancha Ilaiah, Sukhdeo Thorat, so, I started following Gail Omvedt after my Bhima Koregaon… film, I was doing my MPhil. at the time. I’m now working on the final cut of that project. Chaityabhumi is a very small-budget film, made with just Rs 5 lakh, which was funded internally by the community, and not just Dalits but a lot of progressive-caste people also shared some funds. It took me four years (2019-23) to make it and I am feeling happy that the film is getting screened in these many places. I made the film a little musical because music is an important part of the [Dalit] movement. So, this film acknowledges the musicians (Ambika Kamble of Jai Bhim Kalamanch, Dhammrakshit Randive, etc.).

A still from the film.

A still from the film.

Tell us about your previous documentary The Battle of Bhima Koregaon: An Unending Journey (2017). Why did you want to make films on these two places: Bhima Koregaon and Chaityabhumi?

See, Bhima Koregaon… is actually my second film. Before that, I made one short film called I Am Not a Witch. This is a 15-minute film. And I made it because someone told me to make it. There was a person called Narendra Dabholkar. He was a nationalist leader who got murdered in 2013. And Nagraj Manjule and the [Maharashtra] Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti, they arranged a film festival, whose special theme was anti-superstition. So, someone told me that this is the story you can make. And then I made that film, which was selected in that festival, called the Vivek National Short Film Festival. They only selected two documentaries. One was mine. I met Manjule there.

And my second film, a longer film is Bhima Koregaon... I made it because, see, if you are born in a Maharashtrian, Neo-Buddhist family, these places are part of your childhood. They are your memories. And Bhima Koregaon and Chaityabhumi are one of the important memories of my childhood. Until the 2018 violence, Bhima-Koregaon was never part of the mainstream history or mainstream discussion. But people have been visiting Bhima Koregaon for the last 100 years, so, that was the one reason for making the film.

Another thing, I want to show the normal life of the Dalits and their culture. Because whatever films are there, they always show violence and atrocity. I want to show their culture. And this is my culture also. I am not an outsider. That is the main purpose of these two films — Bhima Koregaon… and Chaityabhumi.

What did you make in the time between these two documentary features?

In between the two, I made two short documentaries. One is called Memories of Mangaon (2023). Mangaon is a village near Kolhapur where Ambedkar and Shahu Maharaj started a reservation policy (in the year 1902), decades before India did. Shahu Maharaj was one of the progressive kings from Shivaji’s family. And that conference [Mangaon Conference, March 21, 1920] was the first untouchable conference. And the main organiser was a Maharashtrian Jain, Appasaheb Patil. Maharashtrian Jains also have a very different history. So, that film is about the memories of that conference when it completed 100 years. The other film, There is No Caste Discrimination in IITs? (2023), because whenever the Dalit students commit suicide, they publish one report and mention this one-line note that ‘there is no caste discrimination in IIT’. The film is on the student [Darshan Solanki] who died by suicide at IIT Bombay two years ago, and about the parents’ experience.

You’re doing a PhD on the depiction of caste in Marathi fiction cinema. But the films you have made are documentaries.

Yeah. Fiction is a little bit harder to make, in the sense you need a big production house and you need at least Rs 1 crore. But, I feel, I have a little bit more control in my hand when it comes to documentary films. A lot of the time, I went alone on the field to record. So, even if you have one, two or three persons, you can record and make a non-fiction film. That is the only reason I never tried fiction, maybe. But in the future, I will try, definitely.

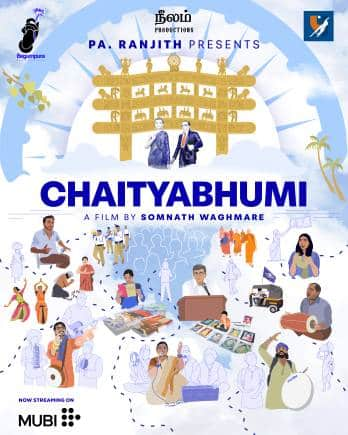

Chaityabhumi poster.

Chaityabhumi poster.

Tamil cinema has Pa. Ranjith, Mari Selvaraj and Vetri Maaran; in Kannada cinema, T Pattabhirama Reddy’s Samskara and Girish Kasaravalli’s films like Ghatashraddha have shown the rot in Brahminical society; tell me about the Marathi filmmakers who have made anti-caste cinema?

See, in my research, I found that the entire Hindi cinema and entire Marathi cinema is highly Brahminical cinema. It’s highly urban, elite, mini-minority stories. And there is another idea that whenever there is film on Dalit, they say it’s a caste film. See, every Hindi or Marathi film is a caste film, just that the caste is different. There is also a pattern. There are two films: Achhut Kanya in 1936 and another is Sujata (1959). When Achhut Kanya released, Ambedkar was one of the prominent figures of this country. He published his Annihilation of Caste (1936), but Achhut Kanya completely deleted him. They replaced him with MK Gandhi. And again in 1956, Ambedkar converted to Buddhism and died the same year but, Sujata, a few years later, also missed including Ambedkar in the film.

Even when British filmmaker Richard Attenborough made Gandhi (1982), which was co-sponsored by Indian government, it completely deleted the Ambedkar character — Gandhi and Ambedkar had a lot of disagreement with each other but they are a part of each other’s life.

But in Marathi cinema, before [Nagraj] Manjule, I only found Jabbar Patel, who has influenced me a lot. And he is a Muslim, he is a socialist Muslim. And he made a biopic on Ambedkar, titled Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar (2000). (Malayalam actor) Mammootty acted as Ambedkar and Gandhi’s character is also there in the film.

Marathi cinema is also very interesting. They deal with a lot of other issues as well. Like in 2009-10, the farmer suicide was the biggest issue in Maharashtra. There are a lot of good films on farmer suicide. So, that kind of films are there, but on Dalits, the entire Marathi cinema and the Hindi cinema have always maintained silence.

I will share another observation on Manjule’s films. Even Manjule’s films are not stories of the mainstream Dalit caste. The main character, even the Sairat (2016) character is from the Koli community. And Koli is a very complicated caste because only in UP and Gujarat Kolis are part of Scheduled Castes. And in Maharashtra, only in one district, they are in Scheduled Castes. And even Fandry (2013), the boy is a Kaikadi, which is again a small caste in Solapur district. So, the four main subgroups (Chambhar, Dhor, Mahar and Mang) are not characters of his films. This hierarchy is everywhere. Within the Brahmins also, there is a hierarchy. Dalit is a social group, within which there are all these castes. So, Pa. Ranjith’s films are more about the mainstream Dalit caste stories. Because Manjule comes from Waddar background, which is, technically, in a lot of states including Maharashtra, these are part of the OBC [Other Backward Classes]. Only in Solapur district, they are in Scheduled Caste. But Manjule’s film, the second character is always a Mahar Buddhist, in both Sairat and Fandry. So, there is a representation.

A still from 'Chaityabhumi'.

A still from 'Chaityabhumi'.

How do you see Neeraj Ghaywan’s Hindi films which have shown stories of the Dalit community? He is going to Cannes Film Festival with his second film Homebound this year. What is your take on his kind of representation?

See, I like his films. I feel there are very few filmmakers in India who is like dealing with the actual reality of society. Especially in Hindi cinema. There is one article on a website called Round Table India, where filmmaker Nishant Roy Bombarde wrote the article ‘From Fandry to Masaan – The Journey of Shaalu Fandry to Masaan, Journey of Shalu’. He criticised Masaan, saying it is a portrayal of the Hinduised Dalit stories, not assertive Ambedkarite Dalit stories. If you see, even Neeraj is actually from Nagpur, his family migrated to Hyderabad, then he studied in Pune. I like his recent film in which the controversy happened, the Radhika Apte one (The Heart Skipped a Beat, in Made in Heaven 2) more. The Buddhist wedding is a very rational thing in Maharashtra. This means you are rejecting the caste system. No media house ever shows the Buddhist wedding. I think, the first time they showed it was when (IAS officer) Tina Dabi’s second marriage happened. Even Indian Idol winner singer Abhijeet Sawant had a Buddhist wedding, and I was checking the records but no media house showed it. Because Buddha and Ambedkar images are there in such a marriage and it implies that they are rejecting Hinduism and the caste system. So, I like Neeraj’s work, mostly that short film.

A still from the film 'Chaityabhumi'.

A still from the film 'Chaityabhumi'.

How do you see the objection to the release for the film Phule and CBFC’s demand for removing caste references, including the names of Dalit groups and to Manu?

The first thing everyone needs to understand is that the Dalits and OBCs and other groups are not minorities in India. One of my artist friends used the word ‘silent majority’. The groups who oppose the film, they are the real minority of this country. That’s why they are so much scared about the caste census. Why one section of the society is opposing the caste census? Because they feel scared. If the caste census happens, then data comes out. Then everything comes into the public domain on who dominates the society.

See, another thing about the Phule film, I think this is the good thing that Bollywood has actually started. Okay, they are like the nature of Bollywood is always like to romanticise the Savarna culture. And I think the filmmaker is also from the same background. I have just one doubt now: what is the film? Maharashtra is a very interesting land, in the context that many people from the dominant caste also, especially Maratha, CKP (Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu), Bhandari, even individual Brahmins, they are anti-caste people. This is the history of Maharashtra. But Bollywood has a saviour complex. What they did in Article 15, if they do the same thing with Phule… I don’t know. I want to watch the film first; because I saw the director’s (Anant Mahadevan) interview recently, where he said I am a proud Brahmin.

And, another thing, (Jyotirao) Phule was not a Dalit, he was an OBC, from the Mali caste. Mali is one of the prominent castes in Maharashtra. So, Phule and Maharashtra have this legacy. Like Tukaram, Shivaji, Phule, Ambedkar and Shahu. But, I think, it’s a good step that they have started making good films. See, Chhaava was their project. Every Maharashtrian know that Shivaji was not communal. Even Shivaji’s son was not a communal. So, everyone knows that. But the same person who acted in a Masaan, now acted in a communal agenda film. And after that riot happened in Maharashtra, in Nagpur and many places, are they okay doing these kinds of communal films?

Even in the non-provocative films like Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Bajirao Mastani (2015), the representation is absent.

Yeah, see this is the old pattern of Bollywood. For me, this is not new. Bollywood has always produced pro-Hindutva films. If you do research, you will find. The nature is always upper caste, Hindutva, Brahmin stories. And they become a saviour of everyone. Even if they tell the story of the Dalit or Adivasi, the upper-caste persons are the heroes of these film.

A still from Chaityabhumi.

A still from Chaityabhumi.

So, which filmmakers have inspired you?

I started in 2014. That same year, Fandry released and Ranjith’s Madras also released. At the time, I was in Pune, which has a film festival culture and students are given free passes. At one such festival, I watched an Iranian film. I love Abbas Kiarostami’s Where is the Friend’s House? His docu-fiction style I like. I also watched some African films there. I remember the film called Themba (2010), on football and HIV. When I watched that film, I understood that cinema can be like this also. And what we were seeing in Bollywood or Marathi cinema was something very different.

You showed your documentary Bhima Koregaon… at the first edition of the Dalit film festival at the US’s Columbia University (where Ambedkar did his first PhD). You’ve travelled globally with Chaityabhumi. How do you explain caste — its complexities and nuances — to the West?

See, I visited the US three times with Chaityabhumi. And almost 20 screenings happen in the US, especially in university spaces and community centres. And I showed Chaityabhumi at LSE (London School of Economics) also, the first screening happened at LSE’s media department. Ambedkar gave this hint in 1936 that you seriously address the caste issue or caste will become a global problem one day. Indians have migrated everywhere and they are making ghettos. So, there are a lot of reports in the US and the UK that the Indian Dalits who migrated to the US are facing discrimination. So, actually, there is a lot of Dalit diaspora in the US and UK. So, in my experience, now in almost every university in South Asia, they started teaching Ambedkar and caste. Even some US schools are adding caste in their syllabus. And, I think, especially post Rohith Vemula, the discussion on caste is really strong there. You see, in the film Origin (2023), made by Black American filmmaker Ava DuVernay, there is a 20-minute section on caste. And there is an Ambedkar character also in the film.

Somnath Waghmare. (Photo: Instagram)

Somnath Waghmare. (Photo: Instagram)

How do you gauge Ambedkar’s relevance today?

Our society is still caste society. The basic structure like marriage, human relations, date, relationships…everything is based on caste. Even among those practising art, caste plays a major role in your psychology. Till the caste society is there, Ambedkar’s relevance will remain very strong. Ambedkar is the most popular figure now in India, in the mass discourse. Maybe, politically, the Ambedkarite groups are weak, but on the cultural level, cinema has already started, but I feel, after 10 years, it will become a wave. And, in the West also, a lot of Western scholars are working on caste and on Ambedkar. Universities in the US, Canada and Australia have put Ambedkar’s statue in their campuses. While, the University of Ghana pulled down Gandhi’s statue, calling him a racist, and they sent a letter to the Indian government asking for Ambedkar’s statue instead.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!