One can never tell if an individual took office with an ambition to make it to history books, or he dealt with what fate threw at him better than others. Either way, Justice Dipak Misra’s stint as the Chief Justice of India was spectacular and filled with milestones.

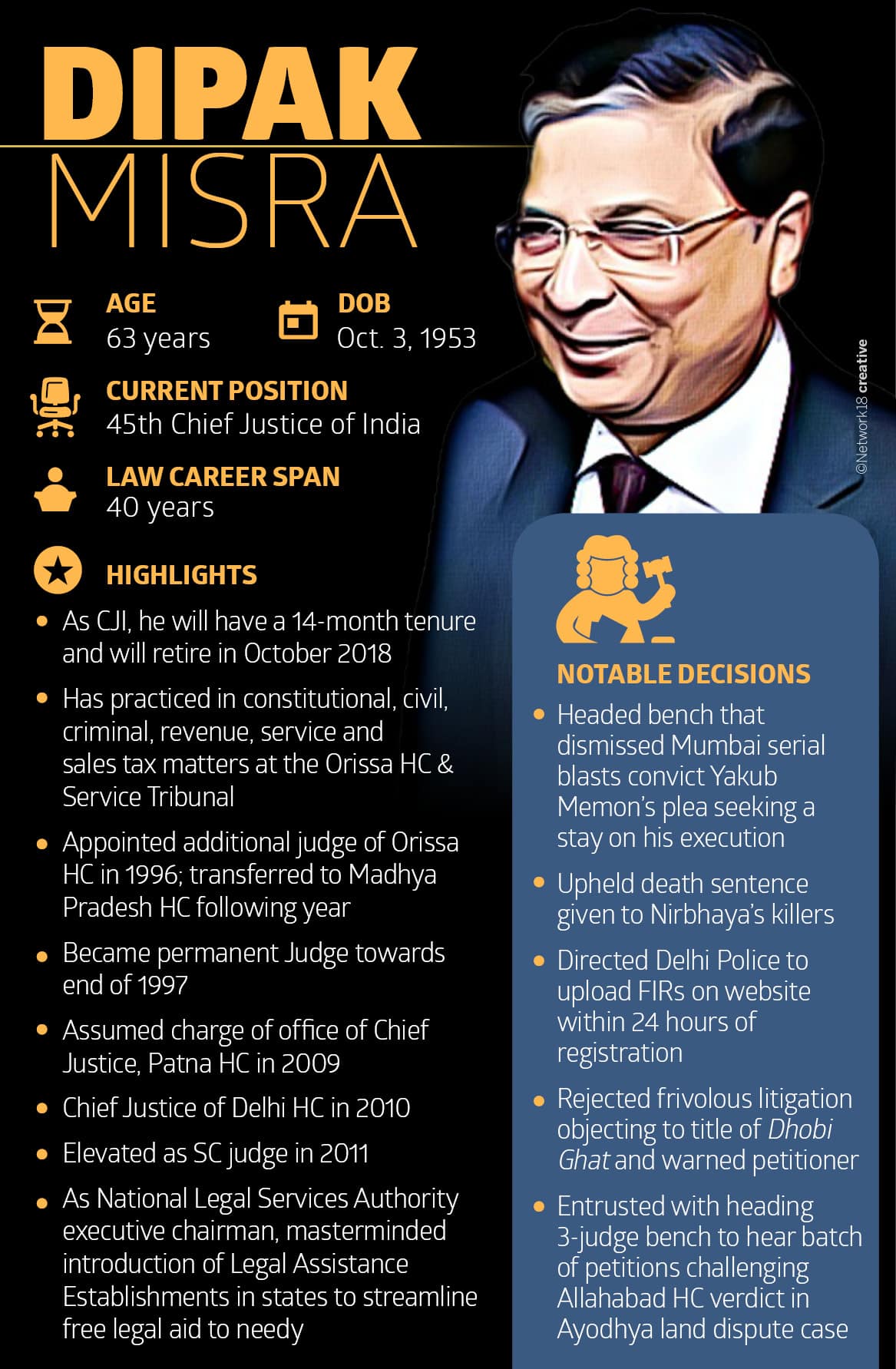

Born in 1953, Dipak Misra began his career as an advocate when he was 24 years of age. He practised in constitutional, civil, criminal, revenue, service and sales tax matters at the Orissa High Court and the Service Tribunal.

In 1996, Misra was appointed as an additional judge of the Orissa High Court; and a year later, he was transferred to the Madhya Pradesh High Court, where he later became a permanent judge.

Misra revels in quoting from ancient Indian texts and western classics in his judgments, which reflects his association with the rich culture that is the legacy of his family in Odisha. In fact, his paternal grandfather Godabarish Misra was a famous Odiya poet.

In 2009, he took charge as the Chief Justice of Patna High Court; and in 2010, he was appointed Chief Justice of Delhi High Court.

Justice Misra was elevated as a Supreme Court judge in 2011, almost at the same time as Justice J Chelameswar.

He has always had his hands full with some of the biggest high-profile cases in his stint as a judge of the apex court.

As a Supreme Court judge, he had headed the bench that turned down Yakub Memon’s plea against his death penalty in an unprecedented midnight court hearing. Yakub Memon, brother of Tiger Memon, was convicted for the 1993 serial blasts in Mumbai and sentenced to death.

Justice Misra was also associated with the bench that upheld the death penalty to the perpetrators of the Nirbhaya case, saying that “if ever a case called for a hanging, this was it”.

As a judge of the Supreme Court, Misra also was very particular about dealing with frivolous petitions – for instance, he disposed off a petition which objected to the name of the film Dhobhi Ghat and warned the petitioner.

Also read | Explained: How is the Chief Justice of India appointed?

In his fairly uphill career, Misra stumbled upon a small bump when four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court – Justices J Chelameswar (now retired), Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph – held an unprecedented press conference in January this year accusing Chief Justice Dipak Misra of “selective assignment of cases to preferred judges” and that “sensitive cases were being allotted to junior judges”.

In their letter to the CJI Misra, they had gone on to say, “The convention of recognizing that CJI is the master of the roster and assigns cases to different benches is for disciplined and efficient transaction of court business and not a recognition for superior authority”, adding that the CJI is “only first among equals, nothing more and nothing less”.

However, the disenchantment among the judges seemed to have faded away, especially after a Supreme Court bench of Justices A.K. Sikri and Ashok Bhushan confirmed, six months after the press conference, that the Chief Justice of India is indeed the “master of the roster” and that “the CJI has the role of first among equals and is empowered to exercise leadership in administration of the court which includes assignment of cases".

During this entire episode, Justice Misra maintained a studied silence, his thoughts and words overflowing only in his judgments, which were apparently unperturbed by the discontent that his colleagues had expressed against him.

Just before the conclusion of his tenure, Misra made a celebrity exit by reading out some of the most historic judgments, including the constitutional validity of Aadhaar, the second longest oral hearing in the history of the apex court.

The beginning of the end of his term as the Chief Justice of India was marked by the much awaited and then celebrated judgment that read down the draconian Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code and decriminalised gay sex.

"I am what I am. So take me as I am" – these words of Dipak Misra from that judgment were engraved in each and every die of the printing press and hopefully will be etched in history. He added, "No one can escape from their individuality...Look for the rainbow in every cloud. Section 377 is arbitrary. "

Later, when he scrapped Section 497 of the IPC, he observed, “Adultery, in certain situations, may not be the cause of an unhappy marriage. It can be the result.”

Another feather to Justice Misra’s cap was the Sabarimala verdict where he observed, “….A woman is not the property of a man”.

After delivering judgments in a marathon week and putting an end to his rather productive term, Chief Justice Dipak Misra will be remembered with respect – not only by his fellow legal stalwarts, but also by the citizens of this country.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!