Exactly 50 years ago, on a sunny day in Sydney, when one of the world’s iconic, feted and daring works of architecture was inaugurated with commensurate royal razzle-dazzle in front of thousands by the British Queen Elizabeth II, the chief designer and architect of the spectacular creation was not only absent, his name even didn’t find mention in public proceedings.

Hearing this story while standing under the colossal wings of the Sydney Opera House on the eve of its 50th anniversary in June this year, it seemed to me that Australia, for a long period, had wanted to forget the wind beneath those behemothic yet benign-looking sails.

Sydney Opera House, was listed as an UNESCO World Heritage site in 2007. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Sydney Opera House, was listed as an UNESCO World Heritage site in 2007. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

For a design as audacious, and an imagination so free, it would have taken more than collective amnesia to omit from memory the man behind the Opera House’s seductive form: Danish architect, Jørn Oberg Utzon.

Situated at the Sydney waterfront at the former aboriginal hub, Bennelong Point, Utzon’s design has stood as testament to a man’s ingenuity for 50 years. The modern world, before Utzon, had little known such geometric temerity in structural design. It is also about the man’s fall from grace — clipping Utzon to size was one of the planks on which a government came to power in host New South Wales, eventually leading to Utzon’s enraged resignation half way down the 14 years it took for the completion of a project which was originally expected to take four years. From an estimated $7 million, the final building cost of the Australian public-funded global showpiece of art and culture came to $102 million.

The Opera house, Sydney. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons))

The Opera house, Sydney. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons))

By its semicentennial year, the story is also about Utzon’s eventual recognition — in 2003, the architect was awarded the Pritzker Prize, widely regarded as architecture’s Nobel, while in 2007, the Sydney Opera House was listed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO.

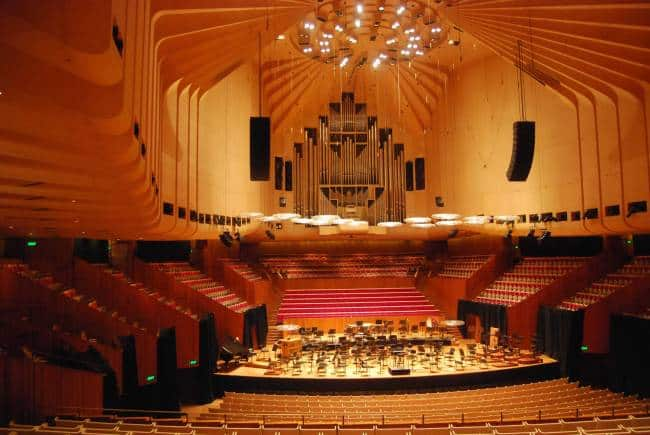

Earlier this year, during a guided tour through the Sydney Opera House on a wintry and windswept June afternoon in the southern hemisphere, our guide, Stephen, carefully took us through some of the Opera House’s legendary venues — the Joan Sutherland Theatre, where in the intimidating hollow of its stage, surrounded on three sides by a near circle of red seats, 70 musicians can together find space; the opulent Concert Hall with its cathedral-akin environment that has hosted the world’s greatest; the smaller and more intimate Drama Theatre and Studio. While Australian architect Peter Hall led the interior designing team after Utzon’s resignation, walking past the scenic glass-fronted foyer opening up to the Sydney harbour, one couldn’t help imagine in scale being under the massive overhead sails of Utzon’s imagination. Or inside the shells, as another popular description goes.

The 200-seater Utzon Room at the Sydney Opera House.

The 200-seater Utzon Room at the Sydney Opera House.

In between, Stephen had walked us through yet another belated acknowledgment of the architect’s genius — the snug, 200-seater Utzon Room, dedicated to his name in 2004, over three decades since inauguration. Utzon again makes an appearance at the steps near the massive Forecourt of the Opera House, his words frozen in a bronze plaque, attesting to the complexity of the work in hand: ‘After three years of intensive search for a basic geometry for the shell complex, I arrived in October 1961 with the spherical solution shown here. I call this my key to the shells because it solves all the problems of construction by opening up for mass production and precision in manufacture and simple erection and with this geometrical system I attain full harmony between all the shapes in this fantastic complex.’ While contested, the story goes that after the local government sponsored a competition to select the design for the Sydney Opera House, Utzon’s entry was selected from a bin of rejects after 233 entries were received from 30 countries.

Utzon passed away in Copenhagen at age 90 in 2008 — never once having visited Australia, or seen his completed creation in person, since leaving in a huff in 1966 after being in the crosshairs of a government minister and having his payment withheld and stature downsized. “Australia’s most famous architecture is Danish,” Stephen declared at the beginning of our tour.

The Dane, inarguably, is also behind Australia’s most famous architecture being its most photographed global masterpiece.

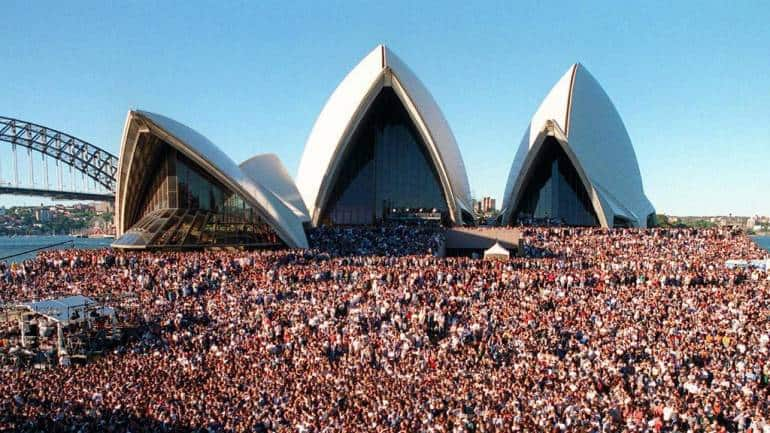

An estimated 10 million people visit the Sydney Opera House annually, about a fifth of them foreigners.

Sydney Opera House, aka the people's house, is thronged by 10 million visitors annually.

Sydney Opera House, aka the people's house, is thronged by 10 million visitors annually.

The Forecourt is as good a place to get a measure of the pull of The People’s House, as it is also often referred to. At any given time of the day, hundreds gather; scores, when I went on yet another visit, drawn like a child to the mobile phone’s LED screen, on a chilly midnight. People gather around the waterfront cafeterias, restaurants and pubs, forming a ring around the Opera House and regaled by the sight of yet another Sydney landmark, the Harbour Bridge.

In the carnivalesque atmosphere, I found myself sharing space with joggers, brisk walkers, a couple in wedding finery with a photographer in tow, a Chinese-looking man walking grimly with what looked like an exotic Greater Bird of Paradise perched nonchalantly on his shoulder and an overwhelming number of Indian tourists — India, reportedly, sends the second largest contingent of tourists to Australia and the fastest growing too.

Everybody's eyes seemed fixed anywhere on the 14 shells, pleasingly representing Sydney’s maritime history and Utzon’s own childhood attachment to the sea. The seductive beauty of the structure and the scenic charm of the Forecourt also provides opportunity for the go-getter among hundreds of noisy seagulls to thieve on unguarded food, while a dozen dogs, the Sydney harbourside’s canine seagull patrol, are trained to prevent such occurrences by chasing away the seagulls.

The Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House.

The Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House.

The Sydney Opera House’s stature as an internationally revered venue for performances has over the years been reinforced by global legends of showbiz — Ella Fitzgerald, Baz Luhrmann, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Brian Eno, Oprah Winfrey, Bob Dylan, Sting, Patti Smith, Prince and Wu-Tang Clan, have in different times, captivated audiences from its stages or the Forecourt.

Participants of a pro-Palestinian rally react outside the Sydney Opera House in Sydney, October 9, 2023. (AAP Image/Dean Lewins via Reuters)

Participants of a pro-Palestinian rally react outside the Sydney Opera House in Sydney, October 9, 2023. (AAP Image/Dean Lewins via Reuters)

The majestic sails of Bennelong has also been an attractive backdrop for activism, the first such act happening even while the structure was under-construction when American singer and civil rights activist, Paul Robeson, climbed the scaffolding to sing Ol’ Man River to a section of the 10,000 construction workers who worked at the site. Activists have attempted to scale the sails to paint in red ‘No War’ in opposition to the Iraq War, while earlier this week, pro-Palestine activists have used the space for demonstrations against Israel. In terms of political significance, nothing have yet matched South African anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela’s speech to a 40,000 strong crowd from the Monumental Steps of the Opera House–his visit being among the first such following his release from prison after 27 years.

Pro-Palestine protests at Sydney Opera House.

Pro-Palestine protests at Sydney Opera House.

During my visit, as part of a team of five travel and non-fiction writers from India invited by Destination NSW, the lead government agency for tourism and the visitor economy in New South Wales, the sails were canvas for a spectacular projection of lights by the feted Australian artist, John Olsen. This was part of the 13th edition of Vivid Sydney, an annual festival of lights, music, ideas and food that recharges the city with its energy and creativity.

John Olsen’s 'Lighting of the Sails: Life Enlivened' animated the Sydney Opera House at the recent 13th edition of Vivid Sydney festival.

John Olsen’s 'Lighting of the Sails: Life Enlivened' animated the Sydney Opera House at the recent 13th edition of Vivid Sydney festival.

Involving a stunning display of dozens of light installations and projections on the city’s landmarks and public spaces, other than curated concerts and food, the absolute showstopper was Olsen’s Lighting of the Sails: Life Enlivened–an animated after-dark projection of the artist’s works on the sails of the Opera House. The sails have previously been used as canvas for projecting obituaries, artwork and controversially, for promoting horse racing. It became the backdrop for scoring bilateral brownie points when it got lit up in the Indian tricolour coinciding with the recent visit of the Indian prime minister to the Sydney Opera House.

The Sydney Opera House lit up with Indian Tricolour recently.

The Sydney Opera House lit up with Indian Tricolour recently.

But here was Olsen’s work, an eye-popping array of vignettes from the natural world, his seagulls finding wings in abstraction on the sails of Utzon’s extraordinary vision. Olsen passed away two months before the Vivid Sydney show, his fate loosely aligned with that of Utzon, who never got to see the completed look of his masterpiece, the Sydney Opera House.

John Olsen’s 'Lighting of the Sails Life Enlivened' animated the Sydney Opera House at the recent 13th edition of Vivid Sydney festival.

John Olsen’s 'Lighting of the Sails Life Enlivened' animated the Sydney Opera House at the recent 13th edition of Vivid Sydney festival.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.