The debate over languages in India is not new, but one that has now found a platform and an audience like never before. Actually, the contention, over which language appears above the other in the list of importance, can be dated back to post-Independence India.

In 1948, the Linguistic Provinces Commission had presented the Constituent Assembly with a report, which was not in favour of organizing states on the rationale of a common language.

The report noted that language in India is not just a medium to communicate, but way more than that. It stated, “Language in this country stood for and represented culture, tradition, race, history, individuality, and finally, a sub-nation.”

The report advised against giving political expression to these “sub nations” as at that time it could be used to jeopardize unity, when consolidation of princely states was the need of the hour. This is when the report suggested the adoption of a national language as a unification force, not realizing that it would trigger a debate that would continue for the next 70 years (and counting).

A vociferous debate in the Constituent Assembly seems to have time-travelled 70 years and projected itself on social media, the only difference being – everyone seems to be an expert here.

What is the conflict about?Last month, Union Home Minister Amit Shah had stirred the hornet’s nest on the occasion of Hindi Diwas, when he pitched the idea of ‘one nation, one language’.

“India is a country of different languages and every language has its own importance but it is very important to have a language of the whole country which should become the identity of India globally,” he had said on Twitter, writing in Hindi. “Today, if one language can do the work of uniting the country, then it is the most spoken language, Hindi,” he added.

His comments triggered nation-wide protests alleging that the proposal was parochial. Judging the sensitivity of the situation, Shah promptly issued a clarification, saying he had only made a “request” and that the Opposition was politicising the issue.

Explaining his earlier remark, Shah said, “A child can perform, a child’s proper mental growth is possible only when the child studies in the mother tongue. Mother tongue does not mean Hindi. It is the language of a particular state, like Gujarati in my state. But there should be one language in the country, if someone wants to learn another language, it should be Hindi.”

Shah’s statements drew flak, which was more pronounced in the South Indian states – pro-Kannada organisations took to the streets in Bengaluru, and protests broke out in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

Irked by Shah’s proposal, AIMIM MP from Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi tweeted, “Hindi isn't every Indian's "mother tongue". Could you try appreciating the diversity and beauty of the many mother tongues that dot this land? Article 29 gives every Indian the right to a distinct language, script and culture. India's much bigger than Hindi, Hindu, Hindutva."

While DMK chief Stalin alleged that the Centre was indulging in “autocratic imposition of Hindi”, actor-turned politician Kamal Haasan warned of a bigger stir in the state than the pro-Jallikattu agitation in 2017. Haasan said, “The unity in diversity is a promise that we made when we made India into a Republic. Now, no Shah, Sultan or Samrat must renege on that promise. We respect all languages, but our mother language will always be Tamil.”

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has maintained studied silence on the subject, quoted Tamil Poet Kaniyan Pungundranar in his UNGA address in New York last week. To which, Chairman of Mahindra Group Anand Mahindra confessed that he was “ashamed” that he did not know Tamil was the oldest living language until PM Modi mentioned it.

This spurred a discussion on the existence and importance of Tamil as a language.

Is Tamil the oldest language?The debate on if Tamil is the oldest language, or if Tamil is older than Sanskrit is exactly on the lines of – which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Experts have found it difficult to fix the age of the language because of its extensive vocabulary. According to a language expert M Srinivasa Iyengar, Tholkappiyam, which is the first literary work in Tamil, dates back to 350BC.

The other Sangam Tamil literature is estimated to be around 5th Century BC, and archaeologists have evidence to prove that. Inscriptions unearthed from Thanjavur have dated the roots of Tamil back to more than 10,000 years.

After elaborate research on Western languages, late professor and author Devaneya Pavanar had established that Tamil is the mother of all languages. In his research, he had concluded that words from Tamil had influenced Latin and English.

The conflict begins when Sanskrit words find mention in Tamil literature or vice versa.

For instance, Thirukkural, a masterpiece of saint-poet Thiruvalluvar, is said to have Sanskrit words in it. Linguistic experts often cite the first couplet which mentions the word ‘Bhagwan’. Experts have argued that Thirukkural does not refer to the Sanskrit word ‘Bhagwan’, but the Tamil ‘Pagalavan’, which means the sun.

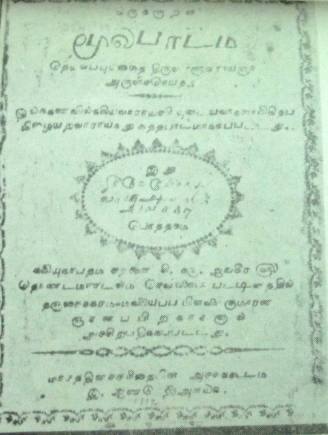

The first page of Thirukkural published in Tamil in 1812. This is the first known edition of Thirukkural (Image: Wikimedia Commons)The first page of Thirukkural published in Tamil in 1812. This is the first known edition of Thirukkural (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The first page of Thirukkural published in Tamil in 1812. This is the first known edition of Thirukkural (Image: Wikimedia Commons)The first page of Thirukkural published in Tamil in 1812. This is the first known edition of Thirukkural (Image: Wikimedia Commons)Former Tamil Nadu chief minister and DMK supremo late Karunanidhi had asserted that Tamil is the mother of all languages at The World Classical Tamil Conference held at Coimbatore in 2010. To buttress his argument, he said more than 20 Tamil words have been found in the Vedas by linguist Robert Caldwell, who had coined the term Dravidian languages and first declared Tamil as a classical language.

For a language to be named ‘classical’, it has to meet three criteria – its origins are ancient; it has an independent tradition; and it possesses a considerable body of ancient literature.

How young is Hindi?While Tamil belongs to the group of Dravidian languages, Hindi belongs to the Indo-Aryan group within the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Most Indo-Aryan languages trace their origins back to Sanskrit, which is regarded as one of the oldest in the Indo-European family.

Present-day Hindi has emerged from various stages, during which it was known by many names. The oldest form of Hindi is known as Apabhramsa, and famous playwright and poet Kalidasa is believed to have written a romantic play called Vikramorvashiyam in it in 400 AD.

Before this, Prakrit was considered to be the language of the masses while Sanskrit was for the elites and the high-borns. In fact, linguists prefer not to refer to it as a monolith and call it ‘Prakrits’ instead. Several Prakrits have been identified, such as Pali – the language in which Lord Buddha (563-486 BC) preached, and Ardhamagadhi – which was Lord Mahavira’s (6th Century BC) tongue.

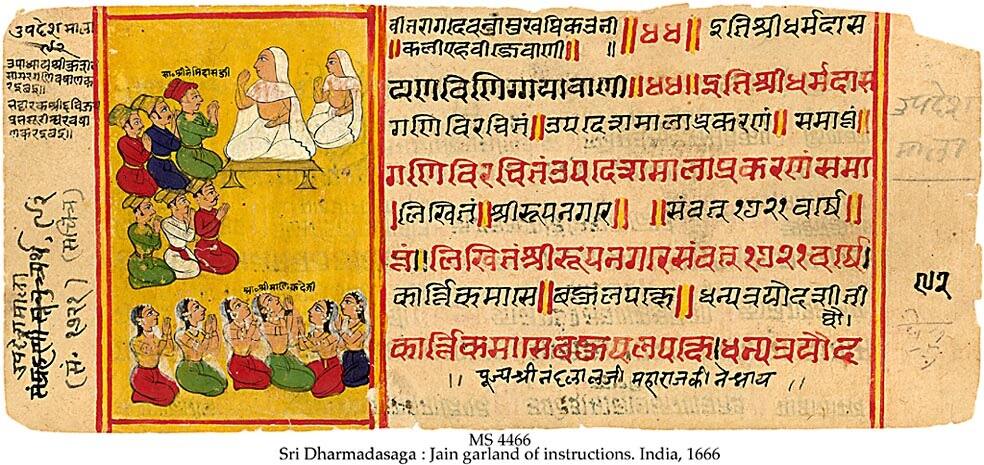

Old manuscript in Jain Prakrit (Image: Wikimedia Commons)Old manuscript in Jain Prakrit (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Old manuscript in Jain Prakrit (Image: Wikimedia Commons)Old manuscript in Jain Prakrit (Image: Wikimedia Commons)Between 100 BC and 100 AD, Prakrit advanced in interesting ways. From a spoken language, it transformed into a literary language. Many plays were written in Shauraseni, Maharashtri and Magadhi, which came to be known as Dramatic Prakrits. Kalidasa has also written his plays in Prakrits.

Gandhari Prakrit, an unusual Prakrit, was spoken in modern-day Pakistan. It was unusual because it was written in Kharoshthi script, from right to left. On the other hand, other Prakrits employed writing in the Brahmi script, which ran from left to right. Gandhari inscriptions have widely been found in Central Asia.

Post the 8th Century, many Prakrits broke up into various Apabhramsa dialects, from which the modern languages were derived in and around 800-1,200 AD. For instance, Maharashtri evolved into present-day Marathi and Konkani; while Magadhi gave birth to languages spoken in eastern India – Bengali, Odia, Assamese, Maithili, etc.

Shauraseni eventually developed into Gujarati, Rajasthani, Punjabi and, later, to what the poet Amir Khusrau called ‘Hindavi’, to which modern Hindi and Urdu trace their origins.

An old Devanagari manuscript (Image: Wikimedia Commons)An old Devanagari manuscript (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

An old Devanagari manuscript (Image: Wikimedia Commons)An old Devanagari manuscript (Image: Wikimedia Commons)The modern-day Devanagari script, in which Hindi is written, came into being in the 11th Century.

Hindi, itself has many dialects depending on the geographical location. These dialects include Awadhi, Bagheli, Bhojpuri, Bundeli, Chhattisgarhi, Garhwali, Haryanawi, Kanauji, Kumayuni, Magahi, and Marwari.

How did Hindi dominate Indian politics?As quoted by the Linguistic Provinces Commission, language in India stands for race, culture, tradition and individuality. During the British rule, it was also given the colour of religion. While Hindus identified with Hindi, in the Khari Boli form; and Urdu for Muslims.

One of the early steps towards the communal division of language was setting up of Fort William College in 1800, where Director John Barthowick Gilchrist ordered the preparation of reading material in Hindi (Devnagari script) for Hindus and in Urdu (Persian script) for Muslims.

As a part of their divide-and-rule policy, the British promoted the use of Hindi to subdue the Mughal rulers. To counter this, the Indian National Congress, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, promoted the use of Hindustani – a hybrid of Hindi and Urdu. The plan, called the Wardha Scheme of Education, was endorsed at the Haripura Session of the Congress in 1938.

However, it was opposed by the Muslim League, which asserted that Urdu was the language of Indian Muslims. This polarisation of language affected the decision-making of the Constituent Assembly post-Independence, and is visible even today. Besides, attempts to ‘Sanskritize’ Hindi and ‘Arabize’ Urdu have further deepened the rift between the two languages.

Meanwhile, on the regional front, there was clamour to organise political units based on vernaculars. The senior leadership realised how it could be counterproductive, inadvertently propelling Hindi to the forefront. Mahatma Gandhi was of the view that “only the language which the people of a country will themselves adopt can become national," the language being Hindi. Even BR Ambedkar believed, “Since Indians wish to unite and develop a common culture, it is the bounden duty of all Indians to own up Hindi as their language." Without this, we would be left “a 100 per cent Maharashtrian, a 100 per cent Tamil or a 100 per cent Gujarati" but never truly Indian.

The sentiment led to an anti-English campaign in the 1960’s, with supporters of Hindi demanding that it replace English for official purposes. In 1963, the Official Languages Act was passed. It maintained that from 1965 English “may” still be used along with Hindi in official communication. This prompted protests from Tamil Nadu, which saw the move as ‘Hindi imposition’.

The DMK consolidated mass support against the move. A comparatively young party, the DMK came to power two years later by using the 1965 agitation in a politically deft way.

Taking cognizance of the growing protests, the then prime minister Lal Bahadur Shastri recalled his earlier proposition of replacing English with Hindi for official communication and said that he would honor Nehru’s assurance that English would be used as long as the people wanted. This was read as the Congress’ decision to not jettison English and not impose Hindi, a decision that won the party a significant number of seats from South India in the 1977 Lok Sabha elections.

This formula, called the three language formula, which allows space for Hindi, English and a regional language has since been operational, except in Tamil Nadu which follows the two language formula.

Poster of the 1939 film 'Punjab Mail'. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)Poster of the 1939 film 'Punjab Mail'. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Poster of the 1939 film 'Punjab Mail'. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)Poster of the 1939 film 'Punjab Mail'. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)The domination of Hindi can also be attributed to the booming Hindi film industry, Bollywood; as well as migration of Hindi speakers to non-Hindi speaking part of India, and increase in population in Hindi-speaking parts of India. On this, Ramachandra Guha said Hindi cinema, over time, “made the Hindi language comprehensible to those who previously never spoke or understood it. When imposed by fiat by the central government, Hindi was resisted by the people of the south and the east. When conveyed seductively by the medium of cinema and television, Hindi has been accepted by them.”

The footprint of Hindi in present-day IndiaAccording to the 2011 Census, Hindi is India’s most spoken language. It is one of the two languages used by the Union government, the other being English.

Hindi is the mother tongue for most people living in North and Central India. There are significant urban pockets of Hindi speakers in most states.

Currently, nearly 44% of India speaks Hindi, although this figure includes languages such as Bhojpuri which have been fighting for a separate status.

Between 2001 and 2011, Hindi speakers grew at a rate of 25 percent, becoming the only one among the 10 largest languages in India, which saw the proportion of its speakers rise.

Hindi has grown at a gradual rate since 1971, mostly because of the high population growth in Hindi speaking states. Between 1971 and 2011, Hindi grew by a staggering 161 percent. On the other hand, Dravidian languages have increased only 81 percent in the same time frame.

In addition, growing migration from N orth to South has resulted in a greater presence of Hindi in the southern states. For instance, in Tamil Nadu, the proportion of Hindi speakers nearly doubled from 2001 to 2011.

This has caused political ripples and triggered agitations in southern states, which is often seen in the form of blackening Hindi signboards and milestones, removing Hindi signages from public places, etc.

According to experts, those reviving the anti-Hindi campaign don’t view it as merely a language affair but as the hegemony of the North; the tussle between Aryans and Dravidians and the introduction of mono-culture.

After coming to power in May this year, the HRD Ministry proposed slight amendments to the National Education policy. Although, it said that the three-language policy be continued in schools, it proposed that the policy be implemented in primary school itself – with students in the 'Hindi heartland' states learning a third Indian language besides English and Hindi; while those in non-Hindi speaking states, will have their regional language, English and Hindi.

The proposal invited the sharpest criticism from Tamil Nadu. DMK chief Stalin lamented that mandatory Hindi from “pre-school to Class 12 was a big shocker” and that the recommendation would “divide” the country.

About 70 years ago, Jawaharlal Nehru had warned of a similar tendency. He had said, “In some speeches I have listened (to) here, there is very much a tone of the Hindi-speaking area being the centre of things in India, the centre of gravity; and others being just the fringes of India. This is what India has to guard against.”

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.