Graphics processing units (GPUs) maker NVIDIA is among the most valuable companies in the world today. Its microchips, like the Hopper series and the new GB10 Grace Blackwell Superchip, are being used to train large language models and power artificial intelligence programmes the world over. In India, NVIDIA signed up with Reliance to build a foundation large language model trained on Indian languages in 2023, and reinforced its commitment to building AI computing infrastructure and an innovation centre in India in 2024. Huang came to India both times, to announce the deals and meet with business and political leaders.

How NVIDIA was formed, and what drives its CEO Jensen Huang are the subjects of a new book, 'The Thinking Machine: Jensen Huang, NVIDIA, and the world's most coveted microchip', by journalist Stephen Witt.

Huang co-founded NVIDIA—just past his 30th birthday; a deadline he set for himself for starting his own venture—with Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem in 1993. In 'The Thinking Machine', Witt lays out the context within which NVIDIA rose—including the battles and mergers in the semiconductor industry starting in the 1990s—as well as conveying something of what makes Jensen Huang, and NVIDIA, tick; and how its chips became central to the AI experiments of today.

Witt explains that part of the DNA of NVIDIA is to always be innovating, and moving to the next thing—which in the present day includes building an Omniverse platform to train robot "brains" via simulations, and then transplanting these brains into physical robots to do tasks like washing the dishes. The company is also working on new lines of AI chips called Rubin Ultra and Feynman—this one's named after Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman—these are expected to ship out in 2027 and 2028, respectively.

Cover of 'The Thinking Machine'.

Cover of 'The Thinking Machine'.

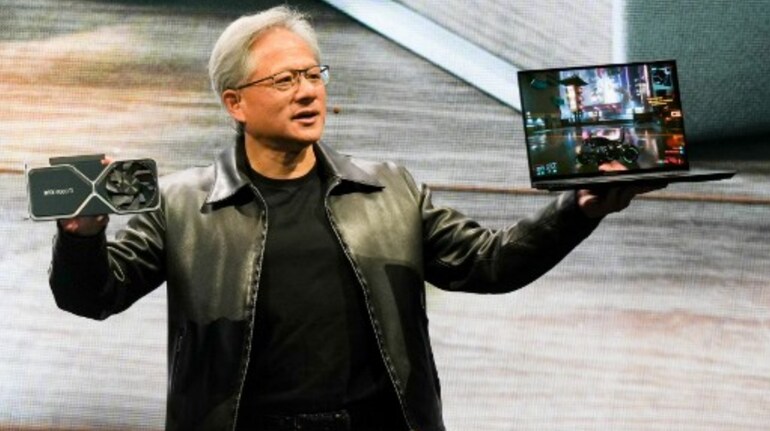

Huang's eventful life makes for interesting copy, too. Plus, "he's an entertainer," Witt says over a video call with Moneycontrol. Edited excerpts from the interview:

You mention early on in your book that there was this one time when you asked Jensen Huang a question and he physically ran away from you—presumably to avoid answering it. What was the question?

We were at a seaside resort where he was giving a lecture, and I asked him a question about his wife -- I think it was. I was like, I guess your wife has been like a big supporter. And he was like, yeah, you know, she has (supported me a lot). And I was like what did she think about these long hours that you work? And he just kind of looked at me, and then he was like, I have to go get on a plane... I thought that was genuinely him trying to avoid the question but in kind of a comic way.

What do you think is the point of this biography?

Jensen's just such a fascinating person, and he really had just a tremendous impact on technology and society. One of his chief scientists, Bill Dally, he used to be the chairman of the Stanford University computer science department, said that without Jensen, none of this technology would be here. Without Jensen, we'd be 10 years behind. And I think it's true. The more I think about it, I'm not sure anyone (else) out there was building these complex parallel-computing structures with no customers (in sight). No one else was going to do that. That was only Jensen's thing.

Jensen Huang is, of course, well-known. He's been interviewed so many times, and he's talked about himself and about NVIDIA's mission and journey around the world. Now, given that so much is already known about Huang and the company he started, did this book present additional challenges?

In Jensen's case, I did three or four times as much research as I normally do. I built this giant paper dossier, a timeline of Jensen's life... when he was born, where he went to school, when he got married, if he had any religious beliefs and political beliefs. Then I watched every interview I could find of Jensen on YouTube. And I noticed the journalists often asked him the same questions. There were whole parts of his biography that hadn't been filled in. Like way back in 2009, he had brought up a time he'd almost died in a car accident. But then the journalist didn't follow up on that, and he never brought it up again. So that was actually my first question to him: tell me about this time you almost died in a car accident. It turned out he almost died in a car accident on the same day that he proposed to his wife... So there was still plenty to learn about Jenson. As you say, Jensen's very open and candid, and that's great.

The other thing about Jensen, it's a little tricky, is he's an entertainer and he's kind of always worried that the audience will get bored. And so this causes him sometimes to embellish his anecdotes a little bit, maybe. He has a lot of stories, but the details of those stories change a bit over time.

In the book, you explain how NVIDIA was putting chips into the Nintendo Switch at the same time as Nobel laureates and scientists were using its chips to do their experiments. Could you give an overview of the work NVIDIA were doing, even before the ChatGPT launch filled up the orderbooks for products like the A100 GPU for training large language models?

Even before artificial intelligence (AI) showed up, Jensen had a small but dedicated band of scientists who worked on his platform. So basically what was happening at the highest demand computing, was Moore's Law couldn't meet it. Historically, the way that we speed up computers was simply to pack more and more components onto a single microchip, shrinking the components and packing more and more onto the chip. But that was running into the limits of physics. Like the components were like one atom wide. And as they got smaller and smaller, they got compromised and they leaked electricity. And when that happens, you can't just rely on smaller and smaller components. You have to do something else. And so Jensen and his team saw this coming as early as 2003 or 2004. They were sort of saying, well, what we have to do is take a different approach. And that was called parallel computing.

And with parallel computing, what you do is you split the math problems up and you kind of execute them all at the same time. Now, this idea had existed for a long time, in fact going way back to the '60s and '70s, but nobody used it because it was difficult to program. And so the computer programmers had a choice between using these parallel computing structures or just waiting for the components to get smaller. And they always just waited.

Bill Dally again said something like, I can't remember the exact quote, but it was basically like programmers had a choice: They could rewrite 1 million lines of code, or wait two years for the processor to just speed up. And so everybody's waited, but then they hit the limits of physics, and they couldn't do it anymore. They're forced to switch. Jenson saw this coming, and he began to attract all kinds of scientists to his platform.

Now, these are scientists who really need a fast computer, much faster than what the average person needs. They're doing quantum physics simulations. They're doing oil prospecting and then later actually two of the Nobel Prize winning groups ended up using this platform. One was doing Ligo, which is the gravity wave observatory. And then a group with this new technique called cryo electron microscopy (cryo-EM) where they freeze the bacteria and then do a 3D scan of them. And both of these just generate huge amounts of raw scientific data. So, how you going to process it, right? You can't put it on a classical computer; it just takes forever. You can use Jensen's high-performance, super-powered parallel-computing platform.

Now, they didn't know AI was coming. In fact, when they made a list of uses for what this (parallel computing) would be good for, AI was not on that list.

They thought for sure scientists are going to want to use this. Actually, fewer scientists used it than they thought. They had a hard time convincing the scientists to switch their code to use this new platform, but they had a much easier time building a completely new field around it. And that's what AI ended up being. And that's where all the money came from.

You've written about his work ethic quite a bit in the book, too. In one section you mention that the day after the NVIDIA IPO, he sent out an e-mail to his team asking for an update on the next thing that they're working on. Is this generally attributed to him being Asian? You write that despite this pressure, people tend to stay at NVIDIA and with Huang for years. How do people within the company see this? Is that something that gave you any sort of pause?

It's interesting because that's a complex question, so let me start at the beginning. Jensen works extraordinarily hard. And as far as I can tell, he always has, his entire life. But neither of his brothers works that hard. So it doesn't seem like there was this cultural expectation, at least inside of his family, to work like crazy. In fact, he told me both of his brothers were terrible students, but Jensen had this inside of himself and at NVIDIA it does seem like everyone worked just as hard as Jensen, even though in the early days almost everyone else who worked there was a white American.

I think he just attracts (that kind of work force). I think the cultural expectations of what NVIDIA is and was and the kind of person that Jensen is and the kind of person that his cofounders Chris and Curtis were, just created this culture around him.

How much of it comes from Asia? It's a really tough question to answer. Technically, you would think, well, all of it. Jensen's just a classic hard-working 996 (9 to 9, six days a week) culture Chinese guy. But he's not actually. He moved away from Taiwan when he was nine years old, mostly grew up in the United States and doesn't seem to have that much exposure to 996 culture. It's almost like he independently recreated it inside of NVIDIA.

Of course, then he connected with Morris Chang and those guys, they were totally 996. They were 100 percent Asian cultural values, 100 per cent work hard and do what's best for the company and don't complain. But it was interesting because John Nichols, who was one of the guys who tried to create the Cuda platform inside NVIDIA was also a total 996 guy and he was a white American. So I don't know if it's something in the hardware business. I don't know if it's just something that that can NVIDIA can create. And now what's really complex is like, OK, so for most of its history, for especially the early part, NVIDIA is mostly white guys. You look at a company photo or video from that time (the first decade and a half), everybody looks like me. You go in there now and, like, nobody looks like me. Everyone's from East Asia, everyone's from South Asia. I would say 1/3rd of the company is East Asian and another third is South Asian. And a lot of them are obviously also there on H1Bs or various kinds of visas. And so their incentive to work incredibly hard is just huge. Plus there're these cultural family expectations that you would work this hard. I talk about that a little bit in the book, the shift into that kind of culture.

I think for Jensen at least that was great. He could absorb that completely.

If Jensen was just some white guy from Ohio, could he have done all this? Maybe, maybe not. It's a tough question.

It was relatively rare (to have a Taiwanese American CEO when Jensen started out in that role at Nvidia in the 1990s), and he was working in hardware. So maybe that has something to do with it. I definitely think that Jensen's cultural expectations of what makes him go, he's almost totally motivated by negative emotions. He's motivated by guilt. He says this. He's motivated by fear; fear that NVIDIA will fail, bringing shame to his family. White Americans, we don't really think that way. So that I think is a very Asian cultural quality.

You write in the book that he's an engineer first and a businessperson later. And that the night before he was supposed to give his first big presentation to Sequoia, he didn't actually have a business plan. The investment eventually came through, but that was despite the presentation, not because of it. What's your sense of how Jensen Huang is looking at the business now?

He has been around long enough to understand that business plans might as well be toilet paper. You have to constantly throw everything out the window. So what Jensen is going to do is build fantastic tools and hope that customers show up for them. But he's not going to do a market analysis, determine the total size of the market and then try to determine product-market fit... In fact, he doesn't do this on purpose because everyone else is thinking that way and it won't get him to where he needs to go. If they had done that with a product like CUDA, the parallel computing platform, it never would have gotten off the ground.

Really, they were doing the opposite. They were saying: 'Here's what's possible, here's what we could build, and let's build it. Let's build that platform and see if anybody shows up to it. We think it's important. And we're willing to lose money on it for a long time because we think someday customers will arrive. But if you ask me (Huang) who and when and how much, I don't care.'

That's pretty counterintuitive, but it does seem to be the way that Jensen works now. He's doing this today; in robotics with his platform Omniverse; and he's doing it with a lot of healthcare applications as well.

For the healthcare applications, the market and the customers are more straightforward.

And obviously robotics is going to be huge too. But the way Jensen wants to do it is very unusual. He's not building physical robots very much. He's instead building this kind of digital gymnasium called Omniverse that robots can learn inside of. So if we want to teach a robot to wash the dishes, that's one of the big use cases, a dishwashing robot, we have two choices. We could do it in the real world and the robot would slowly learn to wash dishes through reinforcement learning, and it would probably break about 10 million dishes along its way, which would be very expensive and a huge mess. Or we can simulate the dishwashing environment: We simulate the sink and code and some kind of high-fidelity physics simulator and teach the robot in there. And then once it's done, we download its brain into a real world body. Jensen's taking the second approach, and I think this is the platform he's building. Whether anyone's going to use it is kind of an open question.

I love that you queued up toilet paper there because there's a story in the book about how NVIDIA looked up a dictionary and almost called themselves Nvision, but then found out that that name was already taken by a toilet-paper maker.

Their (NVIDIA's) original business plan was garbage, it turned out. I mean the first product they shipped was crap and so they had to really kind of invent the company on the fly. Jensen is very good at improvisation, and so I think rather than having some rigid plan he's trying to stick to, he's going to launch a lot of boats and see what's taking off.

In India, and perhaps in Silicon Valley too, there is this romanticized idea of startups: around their origins and within that, what they end up naming the business; what problem they set out to solve in the world, what they can achieve, how much funding, etc. Whereas the NVIDIA founders, you write, were sitting down with spreadsheets and dictionaries to come up with names...

Remember they were starting up in the early '90s, so it's kind of a different era. But the other thing is they were all really a hardware designing startup—they weren't manufacturing, but they were designing and commissioning hardware, which functions in a totally different way. I think in some sense they were, in many ways, not just the classic Silicon Valley (startup). There was like a throwback; they were doing silicon literally in Silicon Valley. So, that's kind of old school.

Their core, the three cofounders, were probably a little more square than like, say, Steve Jobs. They were probably a little more business-oriented, a little more engineering-oriented. They were hard(core) engineers. They were really builders, computer scientists. And I think, at least initially, they didn't really understand what they were getting into. That's often the case with Silicon Valley founders. The ethos, the work that hardware requires; remember, you have to produce and ship hundreds of thousands of physical products every cycle. It's very demanding. (With) software, we can do whatever, we update it later, and not worry about it. The hardware doesn't have that. It's got to physically work. So that's a much more demanding discipline. You need a lot more operations people. You need a lot more engineers. In this way, I think it looks a little different than, say, your classic Silicon Valley star now.

During the COVID pandemic, we heard about this anxiety around semiconductor availability. Were you in touch with Jensen Huang then? What can you tell us about what he was thinking and doing at the time?

I did not really get in touch with Jensen until 2023, after COVID was kind of dying down. But supply-chain disruptions of that type are on the horizon once again, both with (US) tariffs and the potential invasion of Taiwan.

What's interesting is Jensen—at least when I spoke with them a year ago—they had not done a lot of contingency planning. They were just willing to kind of like let this happen. I was very shocked, honestly, and surprised by that. But I think probably now they're thinking differently. Jensen announced this $500 billion investment in the United States. How that actually manifested, what is it they're actually going to invest in? If Jensen was just saying that to keep Trump happy, I'm not totally sure. But it does seem like they're now thinking about re-shoring at least some production (to the US), just because of the geopolitical risk of having everything go through Taiwan.

I asked their head of operations what happens if Taiwan is invaded, what happens if TSMC goes away? She was like, I don't even have any answer for you... she was like, what I think would happen is we end up going to Samsung. We end up going to other providers and then everybody's technology for a few years would get dumbed down a few clicks.

You know, semiconductors are like oil. If the supply is constrained, it will have ripple effects on the global economy in a really serious way.

They're building a facility in Phoenix?

Yes, TSMC is building that. That thing is massive. I think they're prototyping stuff there. I think it's up and running. I want to go out and see it. The Phoenix facility, I don't think they can produce the very leading-edge chips yet, the latest production node, but they can backfill a lot of other supply. And I think probably ultimately TSMC will be able to do that. They announced that they're doubling the size of the investment relatively recently. It's already was going to be huge and now it's going to be enormous.

But remember NVIDIA, it's not just TSMC, there's 40 suppliers that they require to make this stuff go. They'll have to not just get TSMC here (to the US), but like half of Taiwan would have to relocate to Phoenix. Maybe that will happen. Maybe they're going to abandon Taiwan and relocate to the desert. It's not a very nice place, but maybe they could do it. Taiwan's much prettier, having been to both places (I can say that).

In 2024, when Jensen Huang was in India, he spoke about NVIDIA's Indian engineers. From the interviews you did with Huang, what's your sense of where India features into NVIDIA's plans?

I'm sure they're in there somewhere. I know Jensen was in Bangalore last year. I just saw that Apple is relocating a lot of production or plans to relocate a lot of the production to India. I'm sure Jensen is paying attention to all of that. And, in some ways, India is a much safer place to build. Good relationship with the United States, we're allies, you're not immediately at threat of being annexed by China in the way that Taiwan is. The technical talent is obviously there as well as a huge global workforce. Silicon Valley now is like 50 percent people from India, including some of the CEOs. And that was certainly not true like a generation or two ago. That has really shifted.

Even inside NVIDIA, it's amazing how many Indians and Indian Americans work there, which was not true at all in the founding days. I don't think there was a single South Asian person working there for the first 10-15 years. And now several of Jensen's chief lieutenants, including Sameer Halepete (vice-president of VLSI engineering) and Jay Puri (executive vice-president of worldwide field operation) are from India. His chief designer, Arjun Prabhu (vice president of CPU ASIC engineering), is one of his chief architects also from there. So it's obvious that India is producing a very high level of technical talent and could probably, you know, run a platform similar to TSMC if such things are in the works.

The question is, has the geopolitical situation gotten so bad that Jensen just has to build in America now? The problem is American costs are way higher than Asia. Maybe robotics will close that gap. Maybe telecommuting will close that gap, but it doesn't seem like it's going to happen overnight.

Speaking of China, is there any anxiety within NVIDIA around DeepSeek—the stock price of NVIDIA crashed the day after the Chinese AI app launched; around the restrictions that the US government has placed on the sale of NVIDIA's best performing chips to Chinese companies; around the microchip and GPU makers who could come up there while you can't sell in China, which accounted for USD 17 billion in sales for NVIDIA in 2024?

Regarding DeepSeek, there's no anxiety at all. DeepSeek was a good development. He (Jensen) thought the market completely misread it.

There's two or three complicated facets here. So this is going to be a long answer, but I'll start with the beginning.

So DeepSeek, if we take the results at face value, showed that we can train AI much more efficiently on certain kinds of chips. That's actually good in some ways for NVIDIA. The thing to understand is that NVIDIA, their early product was 3D graphics, and what they figured out or intuited quite early was that demand for 3D graphics was infinite. No matter how good you made the video game look, no matter how much processing power you gave it to render graphics, there was a certain kind of customer who was always going to demand better graphics. No matter how much computing power you gave them, they wanted more. And I think that NVIDIA had always looked for another application that had that demand profile. The answer to that was AI: No matter how much, how smart we make the computer, you should just come to it with increasingly complex and sophisticated demands. And that has not been anywhere close to being satiated now. So if we can train AI more easily, this actually just generates more demand for the inference side from people asking the AI increasingly difficult questions. And NVIDIA processes all those questions, so it's actually good for them. So Jensen perceived this to be good for them.

Now the second question is, can we actually believe that DeepSeek really did this (develop its R1 LLM for under-USD 6 million, a fraction of the cost of making ChatGPT, with indigenous design and chips only)? Because over the past year or two, Jensen and NVIDIA have sold a lot of chips to places like Malaysia and Singapore. And there are questions about whether Malaysia is actually the end market for these chips and they're not making their way into China and whether or not making their way to DeepSeek. Specifically Singapore, not that long ago, busted a ring of smugglers who were flipping Jensen's chips; buying them in Singapore and then illegally reselling them into the mainland in violation of like the United States export ban.

So perhaps DeepSeek actually didn't train on such a limited platform. Perhaps their breakthrough was not all it seemed to be. I don't want to accuse DeepSeek of doing anything wrong, but it seems like they want to buy advanced chips for some reason or another. And there's evidence that that stuff is making its way into the country.

The third thing is if Jensen can't sell into China, if his chips don't get into China, that creates the opportunity for domestic competitor, particularly Huawei, the big Chinese chip manufacturer who has been accused in the past of all manner of skullduggery, stealing other people's designs, cloning technology and whatnot. Huawei chips are actually banned in the United States because some people feel that they might spy on us. So Huawei is a big concern for Jensen. He really does not want them to build a competing platform to CUDA, probably because he knows they'll do it for cheaper and just as well. So he's trying to make sure NVIDIA's the player in China so that Huawei doesn't have any room to compete and build its own platform. Because if NVIDIA is banned in China, suddenly that creates a huge opportunity for Huawei to come and replace them with their own AI platform.

So DeepSeek itself is probably not a huge risk to Jensen; it's really this risk that he can't sell. And this was what he was going to Mar-a-Lago and giving Trump money for, the ability to try and get around this export ban and sell his chips to China. Trump lifted the export ban and then a few days later, he reversed it and set it back in. So that was bad for NVIDIA. They had to take a charge.

You also mentioned all the research that you did for this book. Tell us one story that you were not able to include in the book, but which you loved.

This is actually in the Taiwanese edition, but it did not make it into the UK edition: Jensen was called upon to throw a baseball at a baseball game, like ceremonial first pitch, totally meaningless. But when he got out there, he was visibly embarrassed. He was like, 'Listen, I'm not very good at pitching.' He asked the crowd to please turn away. He threw the ball and it kind of came up short and the player had to scoot up to catch it. Jensen kind of grimaced with embarrassment afterwards.

Now, this was meaningless, whether or not he could throw this baseball. But he becomes obsessed with it. This was an irresistible opportunity for self-improvement. So for the next few months, after having $100 billion (in personal net worth) and running the most valuable company in the world, he comes home with his wife and they go to the backyard and they play catch. They throw a baseball around in their backyard every evening. He gets better at it slowly. And the next time he's asked to do a ceremonial first pitch, it's at a Taiwanese baseball game, he goes out there and he nails it. Perfect strike. So this is really who Jensen is. It's perfection. It's embarrassment when you don't absolutely perform to the best standards.

Disclosure: Moneycontrol is part of the Network18 group. Network18 is controlled by Independent Media Trust, of which Reliance Industries is the sole beneficiary.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.