'Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life' was originally published in March 2016. Yet, it is still easily spotted in Indian airport bookshops and is still on bestseller lists on bookselling sites like Amazon. On Goodreads, the book has more than 50,000 votes and an average rating of 3.8. But if 'Ikigai' has come in for a lot of praise in the last nine years, it has also come in for some flak lately.

For one, critics have pointed to the futility of looking for a generalized prescription for longevity and prolonged health span. An underlying tenet of the book, Blue Zones, itself has come under scrutiny after critics pointed to gaps and inaccuracies in age data. (The so-called Blue Zones are five places in the world where an extraordinary number of people live past 80 years and many live to 100 years or more [supercentenarians]. This longevity is attributed mostly to the diet and lifestyle of people in these areas.)

(Image via Wikimedia Commons)

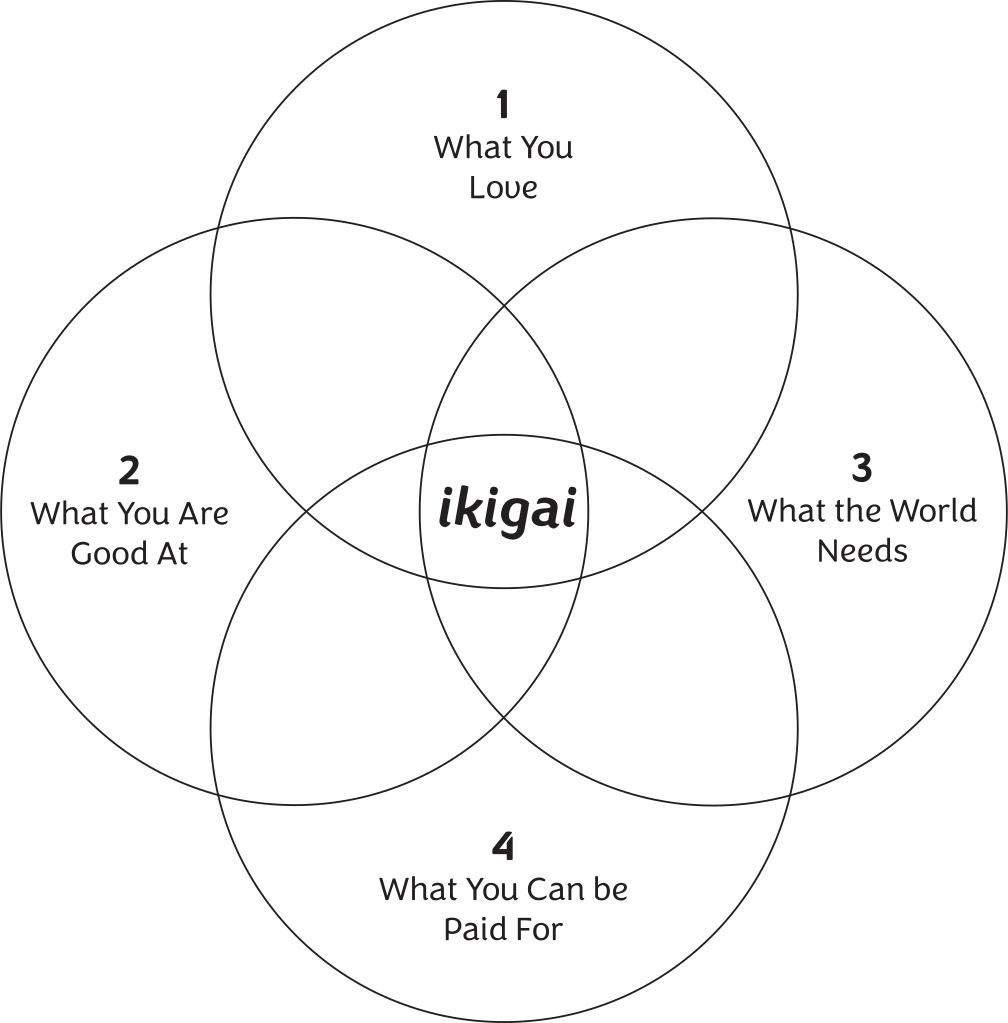

(Image via Wikimedia Commons)Two, some critics have also torn into the Ikigai Venn diagram that advises users/readers to map what they love, what the world needs, what they can be paid for, and what they are good at, to find the overlaps and identify their passion, mission, vocation, profession. One of the key challenges is that Ikigai - the Japanese concept predates the book, of course - translates as things that make your life worth living. It's not about work or work satisfaction alone. (After all, Albert Einstein wasn't playing the violin - one of his two Ikigais; the other was physics and studying the universe - to get paid or do good in the world.)

Having said this, it's difficult to argue with some of the advice shared in the book. Case in point: to remain engaged in activity rather than being bored in retirement. To reduce stress. To sleep adequately (the model's secret). To eat moderately (80 percent rule). To find your tribe (moai) and work on your friendships. To avoid sitting for prolonged periods. To do gentle exercises from Tai chi, Yoga (surya namaskar, for instance), or Qigong...

Miralles and Hector Garcia's new book 'The Four Purusharthas', based on Hindu philosophy, released in August 2024

In a video call with Moneycontrol, coauthor Francesc Miralles explained the central idea of Ikigai, why it can work across geographies and three exercises to improve your concentration and get into the flow state. Edited excerpts:

When did you first come to India?I have been to India five or six times. Many trips have been because of (literature) festivals: in Calicut, Chennai (Hindu Lit Fest), and Jaipur this time. On a couple of occasions, I came only as a traveller. But since the publication of 'Ikigai', I have come as a lecturer or to go to the festivals.

My first trip to India was in 1999 and it was in a very special situation. I was 50-51 years old. I had left my job as a publisher. And I wanted to freelance and to rethink my life; I wanted to be free to discover other things. I was not a writer then. I went with my girlfriend for a couple of months to travel cheaply in India, mainly in the south of the country. And it was in this situation that I wrote my first book. I wrote it in a notebook. It was a novel for children. I can say that India made me a writer.

Actually, I got to know India much before Japan. I started travelling to Japan around 2010, more or less. And I had been to India a decade before. Also as a reader, I remember reading a lot about India as a teenager and also Indian authors. The Japanese way, that came later. And it makes sense because many things that we love from Japan, actually have an origin in India also.

I am not a good spiritual practitioner. In the way that, for instance, I don't like meditating. I know the theory and even in Spain I have done a couple of retreats in Buddhist centers of the Mahayana tradition, but I don't feel interested in meditation because I always say that I want to know others, the mind of other people, not mine, I don't find interesting to myself.

But yes, I have read a lot. For instance, reading many books of Jiddu Krishnamurti. I think it was a very good school (of thought), to know how to think critically and how to explore the main questions of reality.

But you write in Ikigai that meditation is a shortcut to getting into the flow state...One thing is what I do, and another thing is what I know to be good for others. So, of course, meditation is a shortcut to many things.

Meditation is the opposite of our present state of frenzy, of running from one place to the other. For most people doing a set of mindfulness (exercises), meditating 10 to 15 minutes a day or doing some kind of meditation in movement, is a good counterbalance for this quick life.

In my case, my meditation is more playing piano and reading with my five senses, but I know that when I address the reader, I don't expect him or her to sit on the piano. That's just my particular situation.

The subtitle to Ikigai is 'The Japanese secret to a Long and Happy Life'. Is longevity really a worthy goal to have? Why should we be looking to prolong life?More than longevity, what human beings pursue, what we want is quality of life and quality of thought and of movement. As long as we are autonomous, as long as we can move our bodies and have some autonomy and we can follow the life we love, we will want to live to 100 or even longer. But then it depends on the way of life that we have had from our youth. Somebody who doesn't move his or her body, has poor nutrition, who is always running from here to there, working too much, sleeping too little, maybe could reach the 90 or the 100 (mark), but not in a condition where you can have the desire to live. Life expectancy is changing, it's getting broader every time, but it depends on what kind of care we gave to our body and to our mind.

Yes, you write about ageing's escape velocity where the time of one's death gets postponed by a year or more with each passing year. Tell us when and why you travelled to Japan first, and thought about writing Ikigai?Actually, the trip to interview the centenarians in Okinawa, it was maybe my third trip to Japan. Before that I had been there, especially in Kyoto, to write a novel set in this city. That novel, called 'Wabi Sabi', I wrote before Ikigai. But on the second trip, I was introduced to Hector (Garcia) through a common friend, and we started having conversations once a week by Skype. I was guiding him in a novel he wanted to write. And in the end, he did it.

Then on one of my trips, Hector told me that there was a place north of Okinawa in the Guinness Book of Records where they had the highest longevity in the world. His father-in-law - Hector is married to a woman from Okinawa - told him that we should go there and interview all these people. And this was the beginning of the project of Ikigai.

(Image credit: Kunal jpeg via Pexels)You mentioned the longevity of people in Okinawa. But both Blue Zones and the idea that the Okinawan diet could help people in other geographies - whether it is India or Barcelona, where you are based - have come under some scrutiny lately. How do you respond to some of these limitations of the lifestyle tips you're suggesting as a way to live a longer, healthier, happier life?

(Image credit: Kunal jpeg via Pexels)You mentioned the longevity of people in Okinawa. But both Blue Zones and the idea that the Okinawan diet could help people in other geographies - whether it is India or Barcelona, where you are based - have come under some scrutiny lately. How do you respond to some of these limitations of the lifestyle tips you're suggesting as a way to live a longer, healthier, happier life?Actually, life in Okinawa is very similar to the rural life of India or any other place. It's not a matter of it being in Japan or this island. It could be in any other place. I don't know how the Andaman Islands are, but maybe in a little village of the Andaman Islands, you can have conditions very similar to what we found there in Okinawa; and they are common, they have common characteristics with the Blue Zone that were described by National Geographic.

Basically, which are these conditions:

In the Blue Zones, people spend most of the day outside, they eat together, they eat products that are from proximity, that are cultivated in that place. And also these people are very active, in the sense that people don't retire. If you are working your garden or you're working in agriculture, you will go on doing that until you are 100 because this is your style of life, you are used to that, and you don't want to be sitting in front of TV. We can find these conditions, for instance, in the South of Italy, in the island of Icaria in Greece, in a couple of places in America and also in Okinawa. But I am sure that we could find then in India in some villages, some places with the same conditions and with very old people, because it has a lot to do with serenity and activity.

If you are not stressed and you have things to do and you have friends, you can have a lot of fuel to become 100 and even more.

Tell us about the Venn diagram in the book. A large portion of it is devoted to what you do for a living, including what you can get paid for doing it. Now, how important is work to this sense of purpose? And can you find a sense of purpose outside of work as well?Actually, what we observed in Okinawa was that the people who get very old are very active.

After the book was published in more than 50 languages, we went back to Ogimi with National Geographic to shoot a documentary there. And we were brought to the house of the oldest person in that moment - it was a man who was 108 years old. And this man, we found him working in the garden, he was watering the trees, he gave us fruit, he was explaining many anecdotes of his life. And so we understood that there is a relationship between the sense of utility and growing old in a nice way.

If you're sitting in front of a TV or you are sitting in a residence for older people and you have nothing to do, you don't have the motivation to take care of your body, to take care of your mind. You are like in the waiting room of death. The only way to escape from that as long as possible is having something to do. And because of that, in the book of Ikigai, we insist on how important it is that you discover purpose in your life. For instance, if you have a vocation of teacher, even when you retire officially from your school, you can go on teaching in other places. You can volunteer, you can work in NGOs, you can do many things.

There's so much conversation around how things are changing in the AI age. Does the idea of Ikigai need a reset, too, as people re-evaluate their lives and their purpose at a time when artificial intelligence either makes certain jobs obsolete or changes the way we live?I don't think; it has no direct relationship. AI is a tool, just as the computers and the machines in the industrial revolution. The problem with any new tool is that when it's so new, people don't know how to use it. And I think that people are using it in a wrong way. For instance, I was a publisher before becoming an author and I still sometimes work as an editor of projects. I work with authors who are specialists in some topic, and I follow the table of contents they write. I give some advice and I have seen that many people are relying too much on artificial intelligence because I I have experienced situations like this that the author had had to give, for instance, an essay about creativity. And they bring something that I read it and I recognize immediately that it comes from ChatGPT. Because it's working with topics, is working with something that has been repeated many times. So if you ask, write me your opinion about resilience and the text is resilience is this and this and that and this and that, and you have read this in many other books, then you say, OK, if you are using this tool to write your book, nobody is going to read it. Because when you buy a book, what you want is to be surprised when you what you want is the disruption and many people don't understand that.

So I, what I tell to the writers is you shouldn't use this tool in the beginning. You should use it in the end. And why? Because in the beginning, when you are preparing the table of contents of a book of an essay, what you need is pure creativity. So you need to say what nobody said. So if you have the machine, this system works with probability. So and if you want 10 points to talk about creativity, the chatbot GPT is going to tell you the 10 most repeated topics on creativity. And as a writer, you need exactly the opposite. You need to say something totally new. So what I tell to the authors is use your brain, don't be lazy. Try to innovate, try to awake your crazy part, write that, and maybe, when you have finished the book, then you go to the AI and you say, OK, correct me the text, look for repetitions.

But if you do it in the in the beginning, you're lost, you're dead. Nobody's going to read that. That's my experience.

You also know Ikigai for teens...We wrote three books of Ikigai. The first was the one describing the trip, the interviews with the old people, the habits. There was a second book that in English is called The Ikigai Journey that is a practical book. It's a book of exercises, a book in 35 chapters to make activities yourself so that you can explore different parts of Ikigai. And Ikigai for Teens. It was something that an American editor wanted us to write, and it's a book focused in children and teenagers. I would say that it's a good book between 10 years old and 15-16 years old in in this stage of life where you are deciding what can, what could be your path in life. That decision is never easy.

Ikigai has been translated in 70-plus languages. (Photo credit: Feyzanur Babursah via Pexels)Are children thinking about the purpose of their life.

Ikigai has been translated in 70-plus languages. (Photo credit: Feyzanur Babursah via Pexels)Are children thinking about the purpose of their life.Little children, they don't need to learn from Ikigai because they are naturally connected with the Ikigai. You see that when you see little children, but there is one who is singing all the time and the other wants to draw and the other is running. It's more physical. And then we lose these natural impulses with age and with education.

I think the complicated stage is when you are a teenager because you are between two coasts. You are not a child, but you are not an adult, but you have to take the decisions of an adult. And then you finish high school and you have a list of possibilities. You don't know really if you are going to be happy with that. What happens is that many young people study something that the parents said that you can earn money with that. And maybe they study law or business administration, and when they are in college, then they discover that they don't imagine themselves working with it. So, because of that, I would say that between 15 and 17 is a very critical moment in which you take decisions that will affect the rest of your life.

Often people don't really know what they're good at or what they would enjoy doing and you know, for how do you overcome the challenges?When we go to school to 1st courses of university, we work with the four circles of Ikigai.

That is a magical tool that existed before our book of Ikigai. This diagram was used by coaching and marketing purposes. The 1st circle is what you love. So this is the main clue. If you love very much playing the piano and you don't imagine doing anything else, maybe you should do everything what is in your hand to try to be a professional with that. So if you love very much one thing more than any other thing, this is a a very important clue.

The 2nd circle is your talent. What are you good at? Maybe everybody's telling you that you are very good listener, that when you listen to a problem they don't feel judged and that you put good questions and do that you give peace to expression. Maybe you have a soul of therapist there.

Then there's a 3rd circle is what what we can be paid for. So depending on the world, how it's changing and maybe you say, OK, maybe I could do, I could be a freelance in that and work with companies in this way or have my students of that other thing. So this would be the practical way of Ikigai, to understand how it's possible to transform this passion in money. That's a difficult point.

And the 4th circle is what the world needs. And it's another way to get to the purpose. You, you observe a need in the world, you say, OK, the world needs better communication or the world needs more compassion. What can I do from my talent through my purpose to help the world in this way?

So these four circles of Ikigais, we work with them, with young people so that they can write. Actually, it's recommended to do it once a year because you go changing with life. Maybe you discover a talent that you didn't know that you have, or maybe there was something that you liked before, but you don't like it anymore. So human being is a dynamic being, and as Rudolf Steiner said, we change very deeply every seven years. He established a division in blocks of seven years: the little child, the preteen and teenager and then your entrance in in the working world, etcetera.

So if the person changes, the Ikigai can change though. It happened to me when I finished my studies, my college that I studied German language and literature. I was happy as as a teacher of German during 2-3 years and after that I I got bored and I discovered that I didn't have really vocation for that, that it was OK for some years but I didn't have the talent to explain the same once and once more without getting bored and boring my students. Because of that, then I changed to the publishing world. I started translating books and then correcting them and then being a publisher.

So I would say that Ikigai is a dynamic process that you have some clues, You know that I don't know that you like books, but there are many ways to work with books. It depends. You can be a teacher, you can be an author. And so you must be always putting questions to yourself.

How to get into a state of flow. You mentioned Einstein had two Ikigais. Is that right? Can you have more than one?A great many people have two Ikigais. It's very common. Because I tell you for myself, it's boring to do always the same thing. I see no happiness, for instance, in sitting at home and writing 8 hours. This is like going to the office. Human being needs to change from one activity to other and you need to have at least two. And Einstein was passionate about theory and the universe and science, but he had a second Ikigai that was violin. He was not a very good violinist, but for instance, when he visited Catalonia, he gave a concert in the main square of a village called Cadakis. And we find this in many other people and many other great people that they have an official life, maybe. For instance, you have a company or you have built something that for you is important, but then you need like a Plan B, some other place where you can express yourself in a more free way. Maybe because the second activity has not to do with money. If Einstein had been paid playing the violin, maybe he wouldn't have enjoyed them because then he cannot play what he wants, But he has a program. And so I think to find balance in life, it's OK to have an official Ikigai and an spiritual Ikigai. And it will be different for every person. It depends on your abilities, on your talent and what you like and many things.

What does Bill Gates washing dishes and Richard Feynman buying office supplies have to do with Ikigai?It has more to do with flow. There are strange ways to get to flow. Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese monk, has a very beautiful text called cleaning the dishes, where he explains that cleaning dishes can be a meditation if you are totally focused on that. If I am cleaning the dishes, but I am thinking about coming back to the table to have my dessert, then I am not enjoying the warm water and the quietness of doing the dishes in a nice way because then I am not more in the here and now. Everything that you want to do, you must be present. For instance, Richard Feynman - he was a great physicist, of quantum mechanics - he said that he had his best ideas in cabarets. They were a kind of night bars. Feynman said that he had his best his best ideas in those in those places.

The ways in which we can get in flow are mysterious. It may be through music for some people. Greek Peripatetic philosophers said that going to work activates new ideas and you can connect with a deeper part of yourself. For other people, it may be the warm water. Other people find could inspiration in conversation. So you must know yourself and you will find how to switch on this creativity mode and how can you flow better.

The authors have published three books around Ikigai.Could you give two or three exercises perhaps that people can try if they're having difficulty getting into the flow of things?

The authors have published three books around Ikigai.Could you give two or three exercises perhaps that people can try if they're having difficulty getting into the flow of things?Yes. The first one is, disconnect every source of distraction. If you want to concentrate on something, on writing, for instance, put your phone off or disconnect the notifications, disconnect the music, everything that is in the room, and try to be 100 percent there in what you do. That's what Stephen King, in his essay on writing, called closing the door. For him, closing the door is closing the door to everything. So this is one exercise: Cancelling any source of distraction.

Number 2, work with blocks of time. It's difficult to concentrate all day, but if you challenge yourself to be totally concentrated for 40 minutes, this is possible. And then you say, OK, even if I feel uncomfortable, I am doing only this. And this is a kind of training - because we are losing the power of attention, because we are always distracted and trying to answer many things in real time - it's like meditation. The good meditators - not me - they say that in the beginning they could only meditate 10 minutes, but then they can do it for 15 and then 20 minutes. So if you train your attention in very simple things - for instance, say today when I have my dinner, I will concentrate only on the food. I won't be listening to a podcast. I won't be watching TV. I will try just to focus on what I am eating, how are the flavours, and what I am feeling - this is another exercise to train your focus.

And the third one - (Hungarian American psychologist) Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi - explained it very well. He said to attain a state of flow, you need to do something that is not too easy and not too difficult. It must be something in the middle. For example, say you play piano at a basic-medium level, and you're always playing Bob Dylan's songs which have only four chords, there will come a time when you'll get bored because there is no challenge there. And if you try to jump from the Bob Dylan songs to Chopin, you're going to be blocked again because it's too difficult. What Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi said is you must find something that is a bit more difficult than what you can do now. For instance, if you have written five essays in your life and you feel comfortable with that, write your first novel because it takes you out of your comfort zone. You're going to try something different, and you will be awake. So this would be a third piece of advice to be concentrated, to be in flow, trying to put something new in this thing that you already love.

What do you say to people who say 'My life is too stressful and maybe I don't have the luxury really to look for my Ikigai'?There's something very important that we must understand. Stress is not something external. This is a a mistake because in the same city, in the same building where you are living and in the same profession, there are people who are experiencing this as frenetic and others that are very quiet. It depends on your mind and it depends on your organization. If you're if on your agenda, you put 10 things to do on Saturday, then you're stressed. But who's guilty for that? Yourself.

Because stress is not only related with work, it is especially related with free time.

The problem is that the agenda, the calendar of many people, is like the calendar of a minister. They have an activity and a task for every available time slot. What this means is that you can never relax, because you go out for work and then you go to dance school and then you must learn a language, and then you are in a workshop online. Stress is caused by our mind that is putting too much pressure to do things and to get things, maybe for our reputation in front of society.

Just to push that a little further, people may not always have the luxury to organize their day in the way they like or move at a speed that's comfortable for them. For instance, office cultures that champion longer hours or living in a remote village where things like getting water or firewood can't be skipped and take up a large part of your day. It's not really an option to not do those things. Is there space for Ikigai in those situations?Going for water is not stressful. What is stressful is multitasking. If you go for water, just go for water. If you are cultivating, you are doing that. The main source of stress is when we try to do many things at the same time. If you are answering an email and at the same time, you are pretending to follow a conversation, and at the same time, you want to know the notifications of different social media, then you feel that you could collapse.

If you are doing only one thing, even if it's a very demanding thing - for instance, studying Japanese or studying German. You can think, OK, it's a very difficult language, and it is. But if you do only that, your brain can relax because it is only in that highway. And so maybe in the beginning you are a bit overwhelmed, but then you get comfortable with that. The problem is going in and out of this. Say I'm trying to write a letter, but then I go out to see what's happening there, and I come back to the letter... this going and coming back is what makes us exhausted.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.