The fascination of the West with the East has remained an enduring feature. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour, China’s economic growth, and India’s IT revolution may have split the intense focus on Asia’s spirituality quotient, but Europe’s quest for enlightenment in Asia stretches back millennia. The cross-cultural encounter was never a linear path. In the wider imagination seen through the conservative lens of Western Christianity, idolatry and paganism were dominant idioms for Asia.

The British indeed made efforts to learn and master the customs and languages of the subcontinent, which was also fuelled by genuine curiosity and scholarship. Oriental scholars like Sir William Jones and others were convinced that the Hindu doctrine of transmigration was more rational, pious, and effective than the Christian belief of eternal damnation for sinners. Christopher Harding, a history professor at the University of Edinburgh, argues in his book The Light of Asia: A History of Western Fascination with the East that a key driver for Western interest in Asia was the need to introspect and critique their societies.

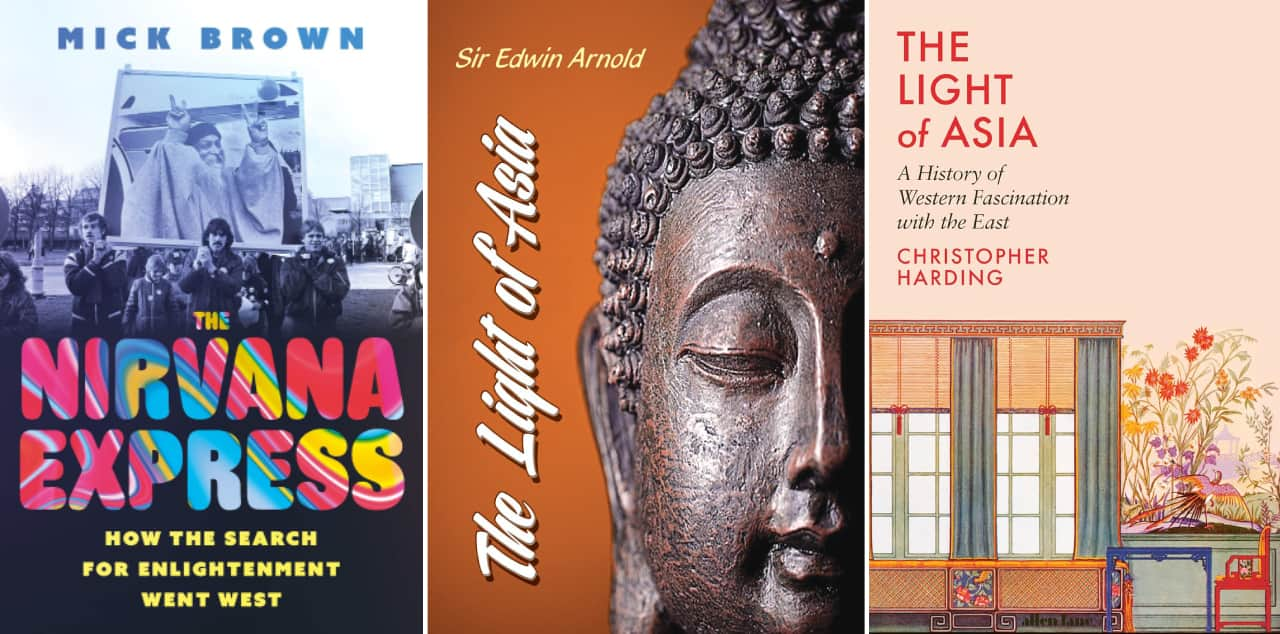

Book covers of The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment went West by Mick Brown; The Light of Asia by Sir Edwin Arnold; and The Light of Asia: A History of Western Fascination with the East by Christopher Harding.

Book covers of The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment went West by Mick Brown; The Light of Asia by Sir Edwin Arnold; and The Light of Asia: A History of Western Fascination with the East by Christopher Harding.

The Roman statesman Cicero, reminds Harding, saw the custom of Sati as proof that women in Rome could learn about fidelity and commitment from Indian women! The Light of Asia was also the title of the phenomenally successful book authored by Sir Edwin Arnold and first published in London in July 1879. As journalist Mick Brown points out in The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment went West, the success of Arnold’s book alarmed Christian missionaries and evangelicals who were concerned about the flock going astray. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, much before he became Mahatma, read The Light of Asia as a law student in London. Arnold’s scholarship was exceptional and so were British administrators like Charles Stuart in their promotion of Hinduism. Stuart himself began his day by taking a bath in the Ganga and advised English women in Calcutta to wear saris instead of whalebone corsets.

Brown’s flowing narrative begins when the British Empire was at its height in India and goes right up to the busting up of Rajneesh. Brown has taken a bold step in highlighting the careers of many charlatans who fleeced Westerners with the promise of sharing the elusive fruit of enlightenment. With quite a flourish, he connects the lives of lovelorn Emily Lutyens, wife of Edwin Lutyens, the architect who built New Delhi, US President Woodrow Wilson’s daughter Margaret, and the grand old lady of the Indian freedom movement, the Theosophist Annie Beasant. As avid promoters and supporters of Indian spiritual gurus, they represented the natural progression since the 16th century when it dawned upon Christian Europe that besides spices and gold, there was more that Asia could offer.

As the East India Company metamorphosed from commerce to administration, it was difficult to resist the demand of evangelicals and missionaries in England and deny them access to the vast religious market of the subcontinent. Christian preachers mastered the vernaculars, and the Bible was published and distributed in all the major Indian languages. It is equally important to remember that it was Annie Beasant who presented Jiddu Krishnamurti as the messiah, and philosophers like Alan Watts, who popularised Buddhism and Hinduism in the West. Although Harding’s strength lies in the medieval period, he has also dealt with trends in the 20th century and resurrects Watts, who died in 1973. Harding’s reasoning of Watts’s prescription of rejuvenating Christianity or adopting Zen Buddhism makes for an interesting read.

In this aspect, Nandini Das’s Courting India: England, Mughal India and the Origins of Empire has the nearly four-year ambassadorship of Sir Thomas Roe in Mughal emperor Jehangir’s court as the primary focus and Das keeps her gaze firmly fixed on the Stuart period. A professor at the University of Oxford in the English faculty, Das has won rave reviews which has also subjected the book to criticism due to the expectation that the author could have dwelt upon current debates on colonialism.

Das’s book is based on East India Company papers, diaries, and the correspondence of Sir Thomas, and she has understandably chosen to restrict herself to what she claims is the period which laid the foundation of English understanding of India and Asia. Three-hundred years after Sir Thomas’s return to England from India, which coincided with the end of World War I, an oil painting of Sir Thomas Roe at Jehangir’s court in Ajmer was commissioned and put up in Westminster. The mural is more in character with Sir Thomas’s belief about his exalted position in Jehangir’s court rather than the grim reality of the “polite indifference” with which he had to deal.

The Portuguese already had a considerable presence in India, so he had his task cut out when he was sent to India on a salary paid, not by the Crown, but by the East India Company. In the overall analysis, Sir Thomas’s sojourn was not a success. He made no effort to learn the local languages, nor did he imbibe elements of the vernacular culture. And although Jehangir and the English ambassador bonded over alcohol, the latter could not extract the exclusive trading rights that the English wanted. During a talk at the Royal Asiatic Society in London, Das described Sir Thomas’s conduct as being informed by a superiority that came from being a European Christian Protestant. Jehangir who has a detailed account of his reign, does not even mention Sir Thomas.

These books show the bewildering history of cross-cultural engagements through various themes and periods. The complexity of that interaction changes over time, but the underlying principles may remain the same. When Sir Thomas returned to England, he pointed out that perhaps it would be a good idea to let people of different religious faiths settle, trade and work in London for the economy to flourish as it did in Mughal India. Four-hundred years after Sir Thomas’s India visit, mobility, visa restrictions, and rights of international students continue to be flashpoints between New Delhi and London.

Sir Thomas Roe had come to India to develop a new market in Asia for English wool as trade routes in continental Europe had dried up. Das tells us that the Mughals did buy wool, but only to make coverings for their elephants. India and the UK are locked up in hard negotiations to finalise a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (FTA). This FTA has acquired added importance due to Brexit and because the UK sees India as a friendly and democratic economy.

Meanwhile, yoga mats have become necessary personal accessories, and the vast majority of Buddha’s busts in Western homes have long ceased to be of antiquarian value necessitating storage in safe houses and lockers, but rather in drawing rooms as everyday functional motifs. Churches are giving way to mosques, temples and restaurants, busloads of Chinese tourists descend to gaze at the spires of Oxford, and Asian kids trump English spelling bees. If we leave away the insurmountable task of assessing who gained and who lost, what is striking is the human yearning to discover, intermingle and interact with new societies.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.