In the works since 2018, India’s e-commerce policy may run into more delays as the government looks to keep the status quo with major players in the sector such as Walmart-owned Flipkart and Amazon at a time when net foreign direct investments inflows has slowed down, according to people close to the developments.

Sources also said that at a review meeting attended by top officials last week, it was informally decided that the policy was not an immediate priority to be worked upon.

The Ministry of Commerce did not respond to an email seeking comments on this development.

When the first draft of the e-commerce policy came out in February 2019, it was seen to be too unwieldy to implement as it touched upon myriad areas of the internet such as data regulation, antitrust measures, intellectual property, and consumer protection, among other things.

After the industry pointed out challenges with the draft, the Commerce Ministry and Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) went back to the drawing board.

“Since then, nobody in the industry has seen a complete revised draft yet. In a meeting that was attended by industry leaders last year, a slide with five bullet points was presented which talked about the broad aims of the policy such as e-commerce companies should do right by the consumer,” said a senior executive of an e-commerce firm.

According to him, the government might have also realised of late that the e-commerce sector is integral to its agenda of growing the number of formal sector jobs in the country.

“The sector currently is estimated to be employing about 2 million workers who get paid between Rs 15,000-20,000 per month. It won’t be easy to replace that… Also, the incumbent players may still put up with a difficult policy as they are deeply invested in the country already. But, a policy environment that keeps on changing is not a good look when you are trying to attract foreign investments,” he added.

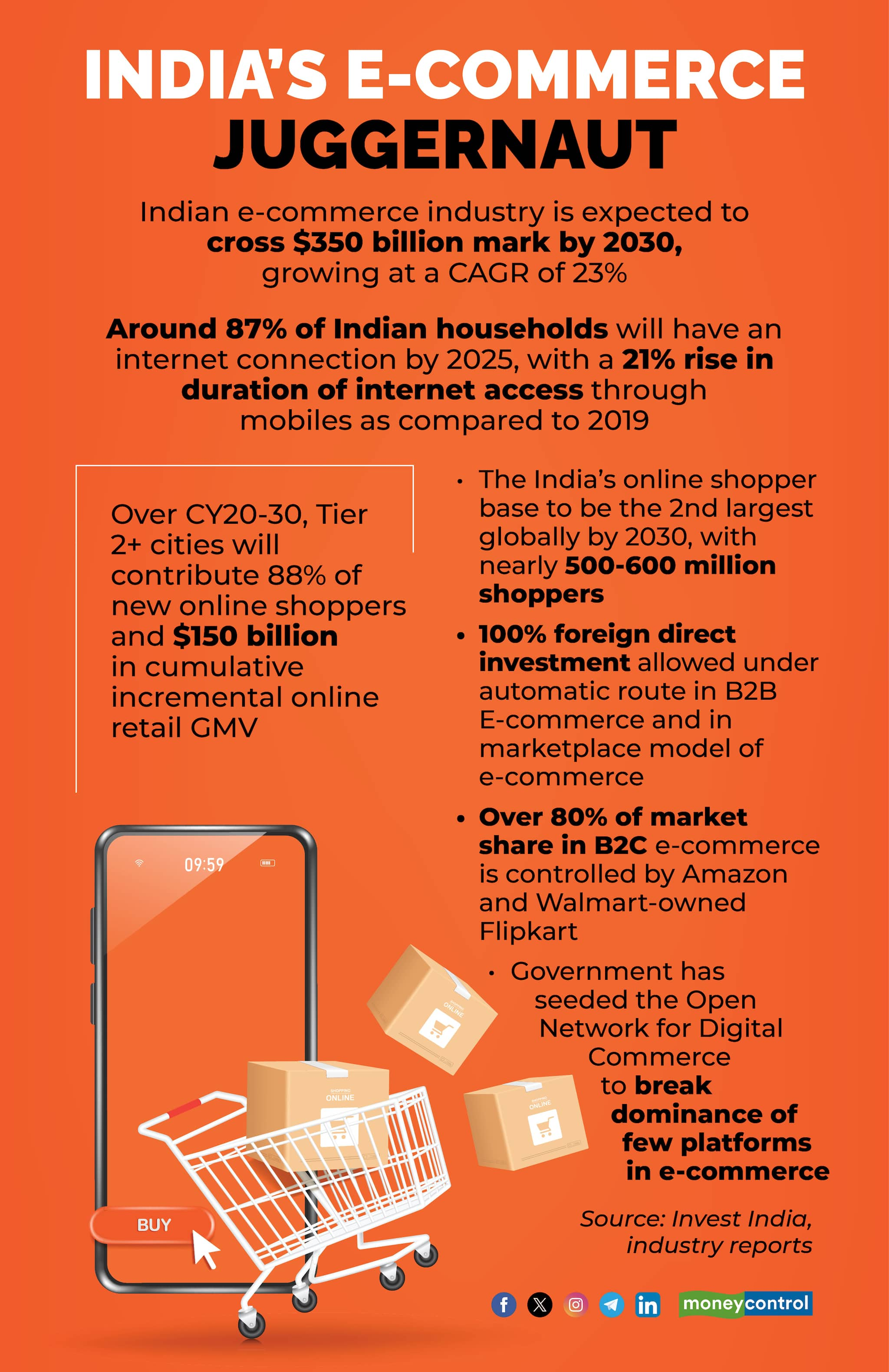

India's $60 billion online retail sector is currently dominated by Flipkart and Amazon which together control more than 80 percent of the market share, according to a report by brokerage firm AllianceBernstein earlier this year.

While Walmart is estimated to have spent more than $24 billion on Flipkart and its fintech offspring PhonePe since 2018 when it acquired the Indian e-commerce unicorn, Amazon has said that its investments in its e-commerce and cloud businesses in India will total $30 billion by 2030.

Latest data from the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) revealed that India’s net FDI inflows contracted 3.5 percent year-on-year in FY24 to $44.42 billion, the lowest in five years.

The last time India’s net FDI inflows came in lower than previous fiscal was in FY19 at $44.37 billion.

Infact, DPIIT Secretary Rajesh Kumar Singh in an interview to Moneycontrol back in April attributed the fall in FDI inflows to geopolitical instability and sticky inflation in some developed markets coupled with higher interest rates.

Singh added that the government is targeting FDI inflows of close to $100 billion over the next five years and aims to further liberalise the policy pertaining to foreign direct investment.

Given this ambitious target, the government has seemingly prioritised consolidating FDI inflows over bringing in regulatory changes in the ecommerce space for now.

Contentious provisionsAs reports emerge from time to time that the new draft could restrict private labels being sold on e-commerce marketplaces, at least two domestic conglomerates are said to have lodged strong opposition with the government.

Another probable provision that has irked the industry, especially the large foreign players, could disallow e-commerce firms from providing adjacent services like logistics and payments.

“The basic premise of a large e-commerce platform is that economies of scale allow them to bundle various services together. You can’t suddenly wake up one day and strike at the heart of the entire business model after billions of dollars have been invested,” said a former executive of an e-commerce unicorn.

Meanwhile, several arms of the government have started working on and coming out with separate laws and guidelines in areas such as data protection, payments and digital competition. Industry insiders say this could be a big reason for the Commerce Ministry and the DPIIT to take a step back and re-evaluate the remit of the e-commerce policy, apart from their differences about its aim.

Last year, Rohit Kumar Singh, the then consumer affairs secretary, told Moneycontrol that his department wanted to protect the interests of consumers, while the DPIIT’s goal was to promote e-commerce. He said this had contributed to the delay, apart from holding 80 meetings with different stakeholders in the e-commerce ecosystem.

A major factor in prompting the government to bring out an e-commerce policy in the first place was protecting the domestic industry and small sellers from the duopoly of Amazon and Flipkart in online retail.

However, a senior industry executive said that the government’s answer to most seller complaints now is to get on to the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC).

“For the longest time, small sellers would complain about every other thing. Now the government's stock answer is ‘ONDC bana toh diya’ whenever sellers raise any issue. The government thinks that ONDC is as neutral an avenue for their growth as possible,” he said.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.