Through his own experience, Siddhartha Chattopadhyay knew he would have to make an effort if he wanted climbing to grow around his hometown of Almora in Uttarakhand.

Seven years ago, when he was looking to get his climbing journey under way, he had just about managed to find a private gym in south Delhi. Luckily for him, he bumped into a small community who would hit the outdoors on the weekends.

But even after visiting established climbing spots like Dhauj and Mangar, not too far from the national capital, he realised that there were just a handful of people chasing the sport.

New world

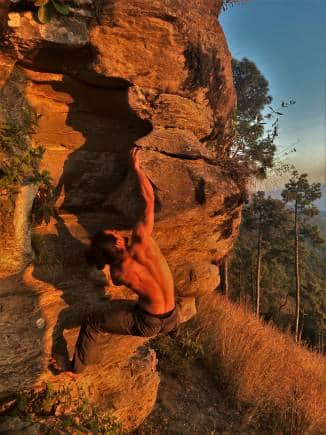

Rock-climbing in Uttarakhand. (Photo courtesy Siddhartha Chattopadhyay)

Rock-climbing in Uttarakhand. (Photo courtesy Siddhartha Chattopadhyay)

For two years since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Chattopadhyay started exploring and documenting areas around Almora. Along the way, he infected two of his close friends with the climbing bug, who soon started venturing out with him regularly.

“As far as my knowledge goes, there was no rock-climbing around Almora. Most locals have gone to mountaineering schools and operated on bigger mountains, rather than boulders and crags,” he says.

“I’ve always been very serious about people who want to learn and wanted to do my bit to ensure that they could climb as much as possible. Today, the community is gradually growing,” he says.

Not every climb was within his means. Once things opened up, he invited friends who could finish some of the more difficult problems. For instance, Yadu Bhageria, a climber from Delhi, managed to climb a route that Chattopadhyay has visualised and named it “Tranqulitiy Base”, inspired by the peaceful surroundings where the boulder is located.

Vikrant (climbing the rock) on a project in Simtola Eco-Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo courtesy Siddhartha Chattopadhyay)

Vikrant (climbing the rock) on a project in Simtola Eco-Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo courtesy Siddhartha Chattopadhyay)

Last year, Chattopadhyay self-published the first guide book to have come out from Uttarakhand called The Essential Guide to Climbing in the Almora Area, where he’s documented various routes that he’s explored over the years. He ensured that the book was easy to use. For instance, scanning the QR code alongside each route leads the climber right to the base of the rock via GPS. And of course, Chattopadhyay was always open to lending a hand when needed.

“Climbing gyms are a hefty investment, but a wonderful place for beginners to get started. That said, going outside is a different kind of challenge. Simply wandering around looking for boulders is insufficient. Climbing spots must be carefully documented, while establishing infrastructure and ensuring access, perhaps through the assistance of a guide,” he says.

“It needs another set of infrastructure that we need to build,” he adds.

Siddhartha Chattopadhyay has been helping build rock-climbing in and around Almora, Uttarakhand. (Photo courtesy Siddhartha Chattopadhyay)

Siddhartha Chattopadhyay has been helping build rock-climbing in and around Almora, Uttarakhand. (Photo courtesy Siddhartha Chattopadhyay)

Over the last few years, climbers like Chattopadhyay have been trying to make the sport more accessible across the country. When it comes to beginners, it’s all about handing them the opportunity to experience the feel of rock, while opening up new areas for seasoned climbers to explore.

Slow start

Climbing on rock goes back many decades in India. A lot of it was on rope early on, until crash pads were more accessible to veterans like Mohit Oberoi, who started climbing in the early '80s. In fact, he even wrote one of India’s earliest guidebooks, Guide to Rock Climbing in and around Delhi, in 2001. Yet, the sport hasn’t seen much growth until recently.

“Back in 2003, there would be three-four of us climbing regularly alongside a few old-timers from Bengaluru. We would randomly ask people to come give climbing a shot. A few stuck around, most never came back,” says Gaurav J.

A few years later, he started a community called Let’s Play Climbing to spread the word. He soon launched a YouTube channel, Passion for Bouldering, where he would post videos of his climbs. He even made a soft copy of the routes he had attempted in Turahalli on the outskirts of Bengaluru, though unsure at the time if others would use it.

“The idea was to let people know where we were climbing, what the routes were. What was missing back then was a community that would hang together in the outdoors,” he says.

Climbing access

Sohan Pavuluri founded Bangalore Climbing Initiatives (BCI) in 2014 to promote localism. (Photo: Praveen Jayakaran)

Sohan Pavuluri founded Bangalore Climbing Initiatives (BCI) in 2014 to promote localism. (Photo: Praveen Jayakaran)

Sohan Pavuluri had a similar experience when he moved to Bengaluru in 2008. Back in the United States, he could readily access information about routes and grades, while he now had to go looking for these things.

“There was this whole culture of “if you aren’t climbing hard enough, you should get out of here”. There weren’t enough routes for beginners, neither was it very age-friendly. The rope skills were also missing. And a lot of it was competition climbing, which didn’t really interest recreational climbers like me,” Pavuluri says.

To bridge the gap, he founded Bangalore Climbing Initiatives (BCI) in 2014. The idea was to find resonance with the general population and inspire them to take up climbing. And promote what Pavuluri calls “localism” — to encourage climbing based on what was on offer in the region.

For instance, Pavuluri is a fan of longer routes, rather than the difficulty or grade of the climb. But instead of heading to the Himalayas to find them, he would make the most of the big slabs and rock walls in areas around Bengaluru.

Sohan Pavuluri, a fan of longer routes rather than the difficulty or grade of the climb, would, instead of heading to the Himalayas, make the most of the big slabs and rock walls in areas around Bengaluru. (Photo: Praveen Jayakaran)

Sohan Pavuluri, a fan of longer routes rather than the difficulty or grade of the climb, would, instead of heading to the Himalayas, make the most of the big slabs and rock walls in areas around Bengaluru. (Photo: Praveen Jayakaran)

During the initial years, he would invest his own money to set up routes and organise workshops. Senior climbers like Gaurav joined hands with him. A few offered funds, before more volunteers helped the scene grow.

They soon started organising paid workshops of various levels — some to introduce newbies to the basics, others to help evolve skills and introduce rescue modules through a tie-up with Professional Climbing Guides Institutes from the United States. The funds gathered were put back into the sport to source gear, maintain existing routes and put up new ones. They soon had a database of 600-odd routes of various grades across some 40 areas in and around Bengaluru. Pavuluri also released a guidebook, “Climbing Guide to Bangalore” to share the information with others.

“It’s a self-sustaining model today, completely driven by volunteers. We want folks to explore the outdoors through it and in turn, create stewards for these wilderness areas. There is a girl as young as nine and a 62-year-old gentleman who are actively climbing in the outdoors,” he says.

Since 2016, Sohan Pavuluri's Bangalore Climbing Initiatives has been organising Romp, an annual festival that brings the community together. (Photo: Abhijeet Singh)

Since 2016, Sohan Pavuluri's Bangalore Climbing Initiatives has been organising Romp, an annual festival that brings the community together. (Photo: Abhijeet Singh)

Since 2016, BCI has been organising Romp, an annual festival that brings the community together. While the first edition had around 20 participants, they had to restrict registrations to a hundred during the last event in January.

“You need to influence behaviour and push traditions to evolve climbing. Romp gives you the motivation to mentor each other and compete, simply for bragging rights. For the rest of the time, access to climbing gyms helps maintain continuity with the sport,” he says.

“Unfortunately it still caters largely to men, though we do try to do things time and again to include various groups,” he adds.

Everyone's invited

A climbing trip to Badami in 2017 helped Gowri Varanashi connect with other women and the following year, she co-founded Climb Like a Woman (CLAW). (Photo: Gayatri Juvekar)

A climbing trip to Badami in 2017 helped Gowri Varanashi connect with other women and the following year, she co-founded Climb Like a Woman (CLAW). (Photo: Gayatri Juvekar)

It’s what Gowri Varanashi also realised in 2017. A climbing trip to Badami helped her connect with other women and the following year, she co-founded Climb Like a Woman (CLAW) alongside Prerna Dangi, Vrinda Bhageria, Mel Baston and Lekha Rathinam.

“There were female competition climbers who were really strong, but not a lot of them were actively taking to the outdoors and pushing their limits,” Varanashi recalls.

“Today, we have women who feel empowered, strong and confident through climbing. At this stage, even five-six of them climbing regularly is a big deal,” she says.

CLAW started organising an annual festival to introduce women to the basics. (Photo: Gayatri Juvekar)

CLAW started organising an annual festival to introduce women to the basics. (Photo: Gayatri Juvekar)

CLAW started organising an annual festival to introduce women to the basics. They set up local chapters in Mumbai, Delhi and Bengaluru to conduct regular gym meet-ups and workshops, and help the community grow. Last year, they offered a grant of Rs 20,000 to two women who were getting started in the world of climbing.

While most of the previous CLAW meet-ups were focussed on bouldering, they organised their first top-roping session at the most recent edition in Badami in December last year. That event was attended by an experienced Polish climber, Ola Przybyszola, who offered to conduct a five-day bolting workshop in February for the regular climbers. For another week, they invited others from the community to be a part of the bolting experience. And by the end of it, they were able to open up a whole new climbing area in Badami, setting up 29 new routes of various grades.

Gowri Varanashi's CLAW organised their first top-roping session at their annual festival last year in Badami in December. (Photo: Amit)

Gowri Varanashi's CLAW organised their first top-roping session at their annual festival last year in Badami in December. (Photo: Amit)

“The tendency is to bolt harder and harder lines, but we also established easy routes so that beginners aren’t intimidated,” Varanashi says.

“We asked a local climber and guide, Ravi Waddar, to name this area — he decided to call it PowerStar after the late Kannada film actor, Puneeth Rajkumar. A few routes also have Kannada names. The idea was to get the local community involved in order to create a sense of ownership,” she says.

Providing access

A veteran in the world of climbing, Anil Belwal, too, has been doing his bit to support local climbers around Nainital. Around three years ago, he started Tony’s Climbing School through which he could help beginners.

“Whenever I go around town, I bump into kids who are really strong but don’t have access to climbing or the money to pursue it. The idea was to have some place where they could come train. I don’t have funding, so I’m unable to do too much since gear is expensive. But I can certainly help them with the basics,” Belwal says.

Equipment is certainly a barrier to entry even today, as is access to the sport and the regions where it can be practised, some of which have been declared off limits by local authorities. But something that concerns Pavuluri more is the lack of information-sharing that he’s observed.

“The population size is still so small in India. Though it’s grown in Bengaluru, it still seems like a long way off before there is enough momentum for it to grow by itself,” Pavuluri says.

In the time ahead, Chattopadhyay is looking to move away from his day job and start focussing on his climbing initiative, RockTrailSleep.

Climbing is not just physically challenging, but is also very meditative and mentally rewarding. (Photo: Gayatri Juvekar)

Climbing is not just physically challenging, but is also very meditative and mentally rewarding. (Photo: Gayatri Juvekar)

“Climbing is not just physically challenging, but also very meditative and mentally rewarding. An activity like climbing takes a long time for people to understand — a few just don’t understand what is it about climbing rocks; for others, there is a certain degree of privilege associated with it. So, it will take a while, but will get there eventually. And I’m motivated to help grow this sport,” he says.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.