Chhavi Rajawat surveyed the stage, shifted a sofa and switched off a light so that the audience could clearly see her PowerPoint presentation. Speaking about transforming Soda at last month's Mathrubhumi International Festival of Letters in Kerala's capital, Thiruvananthapuram, Rajawat narrated the story of development as the two-time sarpanch of Soda village in Rajasthan, with the help of a lot of data and some anecdotes.

"People say changing mindset is difficult," says Rajawat, called the country's first woman sarpanch with an MBA degree. "I don't think so," she adds. Her work as the head of the panchayat of a village that once symbolised all that is wrong with rural development explains Rajawat's rationale. Three years after leaving a difficult job in tough terrain, the former sarpanch is certain that "rural development is not an urban myth".

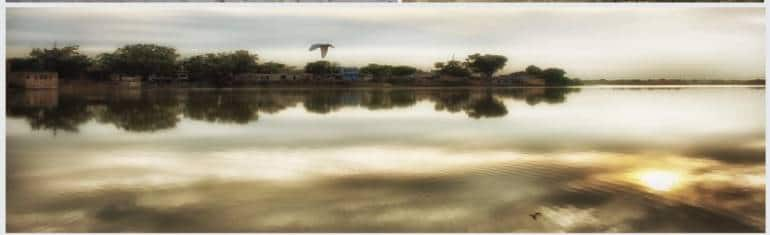

One of Chhavi Rajawat's first initiatives as sarpanch was to reclaim Rajasthan's Soda village's reservoir that had run dry.

One of Chhavi Rajawat's first initiatives as sarpanch was to reclaim Rajasthan's Soda village's reservoir that had run dry.

When Rajawat was elected to the panchayat of Soda, about 60 km south of Jaipur in Tonk district of Rajasthan, in 2010, her village was reeling from the disastrous effects of one of the worst droughts in the state. "The groundwater in the village was declared unsafe even for irrigation," she says about facing the daunting task of providing safe water to protect the residents' health and sustain the village's agrarian economy. "People were drinking water from open ponds and few homes had toilets. More than 70 per cent of health issues were related to contaminated water."

Rajasthan's focus on women empowerment programmes, led by elected women representatives, have previously drawn the attention of the world. In 2000, the then US president Bill Clinton visited the Nayla Village in Jaipur district of the state to meet women panchayat members during his state visit to India. Today, women sarpanchs like Neeru Yadav of Lambi Ahir village in Jhunjhunu district want to help young girls realise their dreams by becoming doctors or playing hockey for the national team.

No proxy leaders

With a population of 10,000 and countless problems, Soda (with a total area of 30 sq. km) had been in dire need of change when the desert state went to panchayat elections in 2010. Of the 12 elected representatives, eight were women. "I became the sarpanch of Soda thanks to quota," recalls Rajawat about the reservation for women in the village panchayat in her first term. The reservation disappeared in the next election.

In the first meeting of the new panchayat, only four of the eight elected women representatives turned up. The other women were represented by their husbands. "It was proxy leadership," says Rajawat, who sent a strong message to the uninvited "leaders" about the importance of elected representatives for the village. "Within five minutes, all the elected women representatives were present in the meeting," she beams. In the second meeting, a telephone call from the husband of the deputy sarpanch, who "wanted my wife home to cook", was duly rebuffed.

Having reclaimed its democratic functioning, the new local body set out to work. A survey of households showed the priorities of villagers: water, electricity (homes had only four hours of power daily), toilets and roads. Their first task was to provide safe water to the village. The solution was to reclaim the village's only reservoir that had run dry. "The last desilting was done 75 years ago," says Rajawat, who was born in Soda. "The government engineers said we won't be able to manually desilt 100 acres of land." There were a few more problems. The panchayat had a budget of only Rs 20 lakh and heavy machinery like earth movers were not allowed in rural areas. "Lack of funding and lack of expertise are major issues in villages," says Rajawat. "Our villages remain neglected even today."

Soda village's reservoir before the desilting work by its new panchayat in 2010.

Soda village's reservoir before the desilting work by its new panchayat in 2010.

"I reached out to the private sector and public sector undertakings, but we didn't get any support initially," says Rajawat. It was May and the harsh summer heat was scorching the earth. "We got some money from my father and his three friends. I also pulled some funds from our family hotel," she says. Someone who heard Rajawat's interview on the radio about the panchayat's desilting work sent a cheque of Rs 50,000. "That reignited my hope in the goodness of the people," says Rajawat, a business management graduate who worked in the private sector before becoming a sarpanch.

Voluntary workers wanted

The panchayat wanted to mobilise the village residents voluntarily for the work. The leader of the opposition in the panchayat came to support. Rajawat's parents, too. The village elders said only those people who lived around the reservoir would join in the desilting, but those who lived away also arrived. Initially, 12 acres of land was desilted. "It rained the next day and the reservoir was full," says Rajawat. "Village is like an organisation though unorganised." Four years later, the Coca-Cola India Foundation would support desilting of an additional 14 acres.

The next on Rajawat's list of development was construction of toilets. "We went door-to-door to understand the priorities," says Rajawat. "The men would speak to me first, but the women would pull me aside and say, 'We want toilets'." Within her first term, nearly the entire village got toilets. Desilting resulted in an increase of 70 per cent of agricultural produce in the village. Animals received water and dairy improved. Soil, desilted under NREGA, soon created roads.

Curiously, education wasn't a demand of the villagers. "Development is perceived so differently in our country," says Rajawat, whose mother, Harsh Chauhan, had opened an all-girls school in the village decades ago. Rajawat has heard stories from family members about how her grandfather, Raghubir Singh, a retired brigadier (and recipient of Maha Vir Chakra) who commanded a battalion in the Khem Karan sector during the 1965 India-Pakistan war, would ask his daughter to drive through the village in early '80s, while he sat in the passenger seat to shed patriarchal mindset. "My grandfather was a huge inspiration," says Rajawat.

Former South Australia water security minister Karlene Maywald during a visit to Soda village, Rajasthan.

Former South Australia water security minister Karlene Maywald during a visit to Soda village, Rajasthan.

Another area on the panchayat's radar was the village's biodiversity. An extensive plantation drive followed. The beneficiaries of new toilets received saplings from the panchayat. Rajawat reached out to the Central Sheep and Wool Research Institute in the nearby Avikanagar in Tonk district to get tips on the kind of grass to grow on pastoral land. "We told villagers not to cut down trees because we need them for water," says Rajawat about her successful attempt to change habits and practices.

"In our first year itself we ensured there would be no more child marriages in our village," says Rajawat. The village also got its first bank and an ATM machine helping the women in saving and budgeting and having their own bank accounts for the first time. While the Soda panchayat focused on providing basic amenities during Rajawat's first term as sarpanch, in her second term during 2015-20, it invested in school infrastructure, especially its primary school and girls' school. The Eminent TT Girls' College in the village, which was defunct, got a new lease of life, too. "Young people began walking into my home," says Rajawat. "The youth became the champions in helping spread our message."

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!