Around the time we celebrated the 76th Independence Day—the national flag aflutter ubiquitously, from slum windows, shaky hands of biker dudes and in every street corner—an exhibition of artworks around Mahatma Gandhi, Bapu in Three Voices, opened at Delhi’s Gallery Espace.

This show follows a long and solid tradition of image-making in the Indian art world, from early 20th century and the Moderns to contemporary artists. No other public figure in India has commanded this kind of aesthetic and visual contemplation across media from simple school or calendar art to complex digital works. In the past few years, we have been seeing Gandhi as more and more removed from the public eye. The art gallery is a rarefied space for most Indians, but here Gandhi thrives.

Bapu In Three Voices, showing at Gallery Espace, Delhi, until 12 September, has three bodies of artwork: digital photographs by Anuj Ambalal, pigment ink prints by Ashok Ahuja and Sharad Sonkusale’s mixed-media canvas panels. All three projects focus on Gandhi’s legacy preserved in museums dedicated to him, the institutions he built, and the books he wrote—offering interpretations of Gandhi’s public and media presence.

Ambalal’s photographs focus on the iconic—and ironic—traces of Gandhi in contemporary India. Ambalal photographically documents large-framed Gandhi images behind the absent bureaucrat’s desk, replicas of his personal belongings languishing in glass cases in museums, shelves in a printing press filled with stacks of unsold books on Gandhi. Ambalal’s series began after he read Gujarati texts written by Gandhi. It was a personal search to create his own portrait of Gandhi through images in the public domain where Gandhi is an inspiring and sometimes controversial presence.

“References to Bapu’s ideology have been encrypted into these images to explore a narrative that is woven with humour, sarcasm, reverence,” says Ambalal.

'Preserved' by Anuj Ambalal

'Preserved' by Anuj Ambalal

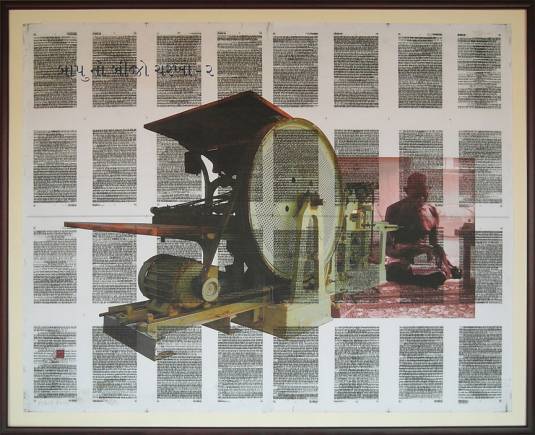

Ashok Ahuja’s prints focus on Gandhi’s belief in the power of pen on paper and the printing press—important tools in his arsenal for Satyagraha. His works, says Ahuja, are “a tribute to a man who astonishingly, with simple black ink, was able to dispel the darkness and spread light, to show us his vision of a bright new world.”

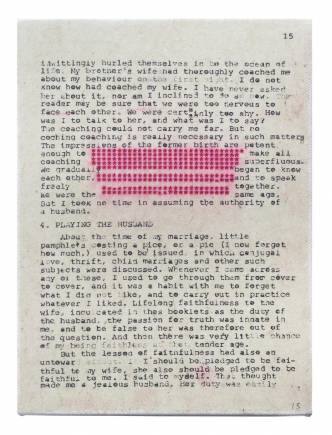

Sharad Sonkusale’s Archive of the Mind is an extended riff on The Story of My Experiments with Truth, Gandhi’s autobiography about his childhood and early youth. It consists of seven panels, each comprising

small canvases covered with rice paper sheets on which the artist has painstakingly typed out the book, besides making other interventions such as marking out a passage in red ink, splattering ink on another, and crossing out a paragraph or covering another with a half circle in black ink. For the artist, each of these textual/visual interventions is deeply personal, arising from experiences and memories that the text

evoked as he typed.

Sonsakule was born in Deoli, a small town in Wardha district of Maharashtra, close to Sevagram, where Gandhi had set up an ashram and lived from 1936 till his death in 1948. The region attracted, while the Mahatma lived and later in the decades following independence, many who set up ashrams and institutions that followed his ideals, many of which survive to this day. For instance, Tukdoji Maharaj, the savant-singer-political activist whose bhajans Sonsakule loves to sing. The works are displayed in panels comprising 49 canvases, an exact square of seven small canvases along each side.

Sharad Sonkusale Panel 1 (detail)

Sharad Sonkusale Panel 1 (detail)

Indian artists have seen and interpreted Gandhi mostly in celebratory ways. This long engagement is the subject of a recent book Gandhi in the Gallery: The Art of Disobedience (Roli Books) by US-based social historian Sumathi Ramaswamy. She uses images of artworks and popular art based on Gandhi and juxtaposes them with her own words, creating a dialogue. She deconstructs Gandhi’s disobedience as an art in itself, and highlights the performative aspect of Gandhi’s politics, as do Ahuja’s works on his writing in Bapu in Three Voices—why and how creatively he would buck a status quo because it’s intolerant and illiberal.”

One of the earliest artworks inspired by Gandhi was in 1930. While photographers and documentary filmmakers descended on Ahmedabad from across the world to cover the starting of the Dandi March, a 27-year-old Dalit artist Chaganlal Jadav walked the 242-miles route to Dandi on the coast of the Arabian Sea in South Gujarat, with his drawing book and pencil. His drawings became a book later, as a live pictorial documentary of the salt satyagraha movement from its beginning to its end.

The India pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale paid homage to Gandhi by showing works that Gandhi has inspired through the 20th century—from Nandalal Bose’s Haripura Panels that were commissioned by Gandhi in 1938 depicting everyday India of the time, women pounding rice, farmers in paddy fields, to Jitish Kallat’s Covering Letter (2012), a dark, evocative and immersive room consisting of a letter Gandhi wrote in July, 1939, to Adolf Hitler requesting him to “save the world from a savage state”.

Throughout his career, Bose painted multiple representations of Gandhi, the most popular being Gandhi on the Dandi March, a linocut print on paper from the mid-1930s. Bose’s bold and precise lines highlighted Gandhi’s simplicity, steadfastness and strength.

These same qualities would characterise practically every sculpture of Gandhi, whether it’s the famous Gyarah Murti by Devi Prasad Roychowdhury that stands at the intersection of Sardar Patel Marg and Mother Teresa Crescent in New Delhi; or the highly conceptual Monumental Gandhi sculptures by A. Ramachandran, which show Gandhi’s head rising above a smooth bronze sheath; or any of the cheap Gandhi-themed souvenirs on sale at tourist spots. They all play upon the contrast between the frailty of Gandhi’s physical form and his strength that enabled him to outwit the British. The pavilion also had G.R. Iranna’s Naavu (We Together). In 2012, Iranna nailed hundreds of wooden slippers on a wall to create this work, symbolising the Dandi March—all the slippers acquired from different parts of India.

Bapu's Other Charkha, by Ashok Ahuja.

Bapu's Other Charkha, by Ashok Ahuja.

And there were, of course, works by Atul Dodiya, an artist whose engagement with Gandhi runs through his entire oeuvre—in the last two decades, Dodiya has done more than 200 paintings on Gandhi. Whenever I have met Dodiya for interviews, Gandhi comes up. Dodiya has said that he has always found Gandhi as a character “approachable”.

“As I reflected on him, I began to feel he was India’s first conceptual artist, who used various ways to convey his message and reach out to people — look at the sheer act of picking salt at Dandi. Aesthetically, he began to encourage me,” says Dodiya.

In 1997, Dodiya did a series of paintings, including Lamentation, that brought together Gandhi and Picasso. For An Artist of Non-Violence (1999), he moved away from his usual oil on canvas to paint watercolours, which were minimal and seemed to him more appropriate for Gandhi’s attitude towards living.

Based on a work by Gujarati poet Labhshanker Thaker, Bako Exists. Imagine (2011), a text-based work consisting of 12 paintings, an installation with nine wooden cabinets, had a young boy, Bako, engaging in a dialogue with Gandhi. This is one of Dodiya’s seminal, large-scale works. Words scribbled in white on a black canvas, some of which are mounted on wooden frames, resemble blackboards. The words could be written in chalk, except they are oil on canvas, rubbed on the edges to create an effect that looks like chalk smudged by a duster. On each canvas, occupying a secondary, corner position, are figures made with oil and marble dust. The words are English translations by Arundhathi Subramaniam and Naushil Mehta of a work of absurd fantasy, Bako Chhe Kalpo, by Gujarati author Labhshankar Thaker. “It is a work that has been with me for many years. The idea of a 10-year-old boy having a conversation with Gandhi, not about big ideas of nationhood or patriotism but of ordinary things, reminds me, personally, of a lost time,” said Dodiya.

In the series Mahatma and the Masters (2015), Dodiya brought together Gandhi and modern occidental artists, such as Mondrian and Duchamp—juxtaposing the quest for India’s Independence with the demand for creative freedom.

So every aspect of Gandhi, who dismissed paintings and art as an indulgence but was savvy about the power of the image in his own politics, thrives in the imagination of Indian artists till today, as the Gallery Espace exhibition shows. But as Ramaswamy points out in her book, nobody has really critiqued Gandhi’s views on caste and gender in art. There are no known women artists who have used Gandhi as inspiration. Ramaswamy also suggests that since the 1990s, artists have used him also as a crutch to critique much that they were seeing as wrong around them—in a YouTube discussion on the book, Ramaswamy says that what has captured artistic imaginations is “Gandhi’s capacious pluralism, rejection of capitalist consumerism, his tolerance for righteous difference.”

Rarely has Gandhi come down from a pedestal in Indian art. In 2010, a work by Aurangabad-based artist J. Nandkumar was forced to be brought down from his solo show at Mumbai’s Nehru Centre. After reading the fine print of Pune Karar or the Pune Pact, an agreement between Gandhi and Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar which laid down reserved seats for “the Depressed Classes” in provincial legislatures for which elections would be through joint electorates, Nandkumar made Gandhi (After Pune Karar). An acrylic on canvas, it depicted Gandhi’s walking stick as a trident at the upper end, and the lower end as a lance piercing the body of a Dalit, signifying how Gandhi may have killed the political rights of Dalits in the country. Critics thought it was Nandkumar’s way of showing upper-class cultural nationalism.

In the age of fast digital reproductions of images, Gandhi has several avatars. He is on T-shirts and other everyday objects, and in product design vocabularies around the world. How Generation-Z artists and their successors see Gandhi and whether they want to interpret Gandhi in enduring ways will probably depend on how accessible and relevant his ideas are to emerging dialogues about politics and protest. For now, the gallery is a good place to rediscover him—or challenge his politics.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.