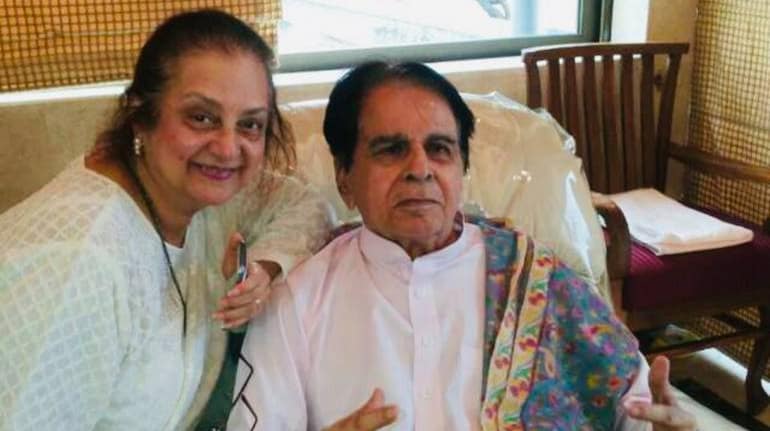

In the last few decades of his life, Dilip Kumar lived an intensely private life, sporadically showing up on his social media handles with pithy posts about films he had seen, cricket matches he had enjoyed and famous Bollywoodwallahs who would drop by at his Pali Hill bungalow.

Several years ago, when his autobiography was released, he made an appearance in front of the press in his wheelchair—more distraught than bedazzled by the flashlights.

In his quiet second life, he had Saira Banu, his partner, wife, caretaker and former star, by his side. Udaya Tara Nayar, the journalist who co-wrote the memoir Dilip Kumar: The Substance and the Shadow had told me years ago when I met her for an interview, that Saira still often called Dilip “chico”, a name that stayed with the actor from his days as a sandwich stall owner in his late teens at Pune’s Wellingdon Club—ladies who visited the club fondly called him “chico”, meaning “lad” or “boy” in Spanish.

***

Dilip Kumar wasn’t handsome the way the other two stars of the Nehruvian hero triumvirate of the 1940s, 50s and 60s—Dev Anand and Raj Kapoor—were handsome. He was tall and wiry with a high forehead that amplified his intensity and gravitas. His deep-set eyes deepened more when he smiled. But he was, like the other two men, no less a ladies’ man. Tabloid press has written reams about his affairs with Madhubala, Kamini Kaushal and the short marriage to Asma Rehman, whom Dilip Kumar dismissed in his memoirs as “a lapse of judgement”.

But Dilip Kumar wasn’t easy to love on set. Directors and actors who have worked with him have recounted in books and film magazines how painfully “method” he was—before Marlon Brando, who was two years younger than he, made method acting mainstream aspirational for actors around the world. Legions of great Indian actors, including Naseeruddin Shah, Amitabh Bachchan and Kamal Haasan have said they have emulated Dilip Saab in some way.

Dilip Kumar’s gaze was always inward. He was a fussy and passionate man who tried hard to make cinema and the world his own. And because of his devotion, Hindi cinema of the 1940s, 50s and 60s allowed him that toil and celebrated that toil through his unquantifiable oeuvre of more than 60 films.

***

Acting was Ashok Kumar’s gift to Dilip Kumar. In 1940, when he took up a job at Bombay Talkies, he watched Ashok Kumar on set every day. Owner of Bombay Talkies, Devika Rani, christened him in the early 1940s at her Bombay Talkies office, then in Pune, because at the time, a Muslim name was anathema to producers. Ashok Kumar even gave him formal lessons on acting. In 1944, when Dilip Kumar’s first film Jwar Bhata, a musical romance, released, critics were largely indifferent. In the late 1940s, Mela and Andaz swung his career around.

The Dilip Kumar characters that every fan will remember are from the late 1940s to 1960. Dilip in Andaz, Ashok in Babul, Vijay in Jogan, Shamu in Deedar, the eponymous Devdas, Devendra/Anand in Madhumati, Gunga in Gunga Jumna—they are carefully chiselled heroes and characters.

Acutely self-aware, egotistic as well as rebellious, what sets these characters apart is an intricate self-pity. The great actor found his energy in this doomed combination—ego, defiance and self-pity. Grief swelled between the lines he delivered; there was nothing playful or spontaneous about Dilip Kumar’s acting.

By the 1960s, he had established himself as the “tragedy king” of Hindi cinema. Tragedy also became him by then. In London, he visited a psychiatrist after a spell of depression. On the advice of the psychiatrist, he decided to play goofy characters in films—like his role in Gopi in 1970. Comedy, in his fine wiring, became slapdash and had no soul. Most of these films also backfired at the box office.

Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor in 'Andaz' (screen grab).

Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor in 'Andaz' (screen grab).Around this time, a watered down version of Wuthering Heights, Dil Diya Dard Liya (1966), won the fans back. His Heathcliff, Shankar, dizzy in love with Waheeda Rehman’s ethereal Roopa, roused all the gravitas back to the battered lover, living up to the self-loathing, emasculated, drunk lover of Bimal Roy’s Devdas—but in a much more sophisticated vein.

Shakeel Badayuni’s lyrics in Dil Diya Dard Liya, “Koi sagar dil ko bahalata nahin; Phir teri kahini yaad ayi” was as eviscerating an anthem of male dejection as “Kaun kambakht pita hai bardasht karne ke liye; Hum to peeta hain ki yahan par baith sake…”

***

Dilip Kumar’s cinema wasn’t directly political or socio-political in spirit, but he attracted enough controversies. Equally proficient in Urdu, Hindi and English, through the 1980s, he faced unfair public scrutiny from the Hindu right. A former nominated member of the Rajya Sabha, he was never in electoral politics. His secularism, questioned on many occasions, is in the broadest sense of the word—a philanthropist, he has fought against the censorship establishment, and for freedom and human dignity.

In Gunga Jumna, the censors wanted the last words of his character, “Hey Ram”, cut—how could Dilip Kumar, a Muslim, use the same last words as Mahatma Gandhi, even if it was only on screen? He was accused of being a Pakistani spy based on some bizarre grounds. He was the target of the Shiv Sena’s ire when Pakistan bestowed its highest honour, the Nishaan-e-Imtiaz, on him. By then, he was in his 70s, and unwilling to fight.

July 11, 1999, photo of Dilip Kumar (left) and then Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee. This photo was taken at meeting in New Delhi, soon after the Shiv Sena asked Kumar to return "Nishan-E-Imtiaz". At the meeting, Vajpayee said it was up to Kumar to return the award, and no pressure should be put on him. (Photo: Sunil Malhotra/Reuters)

July 11, 1999, photo of Dilip Kumar (left) and then Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee. This photo was taken at meeting in New Delhi, soon after the Shiv Sena asked Kumar to return "Nishan-E-Imtiaz". At the meeting, Vajpayee said it was up to Kumar to return the award, and no pressure should be put on him. (Photo: Sunil Malhotra/Reuters)The passing of Dilip Kumar is the passing of a sensibility already in the trenches of 20th century cultural cache—the sensibility in which progressive ideals that fuelled a new secular nation in the years following Independence informed all of the arts. It transcended religion, language and ethnic barriers. Dilip Kumar invented a delicately rehearsed ego within this sensibility that showed Indians through their most-loved and most-popular art form, cinema, that machismo doesn’t always define the most complex, elegant and enduring masculinity. That’s enough reason for the beautiful Dilip Kumar to live on, beyond Generation Z-plus.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.