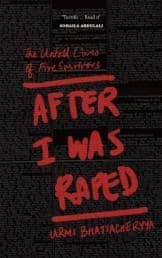

Delhi-based independent journalist Urmi Bhattacheryya’s debut book After I Was Raped (Pan Macmillan India, Rs 399) tells the story of five survivors of rape and gang-rape. Even while laying bare the apathy, cruelty and injustice that survivors of sexual violence have to deal with during and after the assault, the book is grounded in empathy, objectivity and a sincere search for solutions.

Bhattacheryya writes for various national and international publications on issues of sexual assault, women’s health and culture. In 2020, Bhattacheryya won the UNFPA Laadli Award for Gender Sensitivity for her reporting on child sexual abuse.

We asked Bhattacheryya about her key learnings from her years of research.

You have interviewed rape survivors from varied backgrounds in this book. What were the main insights about violence against women that you gathered during these interviews?

You have interviewed rape survivors from varied backgrounds in this book. What were the main insights about violence against women that you gathered during these interviews?

That it is a systemic and systematic problem, and it isn’t going to go away without active, concerted effort. That we still don’t hold men responsible and accountable – both for the crime of rape and for rape culture that perpetuates it.

Men aren’t held responsible – particularly, cisgender heterosexual men – because that’s what patriarchy does: make one loath to question the abusers of power – men themselves.

Until we stop tiptoeing around this problem, until we stop judging women for their clothes, how late they were out at night or not (sometimes, inadvertently – sometimes, blatantly – saying women “deserved that rape”), the crime will continue unabated.

We need to hold men accountable; we need to dismantle patriarchy and rape culture so insidious that it excuses men and protects them from the law, and disadvantages women.

Most of the women I spoke to for my book belong to socio-economically underprivileged communities; two of my case studies are Dalit women who were subjected to the utterly invasive, humiliating and unnecessary two-finger test.

These women were raped to be “shown their place”; in the context of the Dalit survivors, the rape occurred as a result of dominant-caste anger at the woman “stepping outside” dominant-caste-delineated caste lines. Their rapes were committed by men who fully believed they would get away with it, despite living in close quarters, and/or being related to the survivor, and/or having known the woman/child for some time.

They were entitled and their entitlement is a horrifying indictment of rape culture in India: they know all that is to know – that the woman might not report, that she and her family might succumb to intimidation or reminders of “family honour”, that cases would drag on for years and that they would ultimately go scot-free. We need to stop placing an idea of honour in a woman’s vagina and place culpability solely in a man’s violation of her consent, agency and body.

The stories are indeed heartbreaking, especially since some of the women are still living in close proximity to their rapists. How did you deal with the personal emotional impact of speaking to them about their experiences? How did the research of this book change you as a woman and as a journalist?

That was one of the hardest things to encounter – the microcosmic, claustrophobic after-effect of a crime that doesn’t end with the crime itself.

As you’ve rightly noted, most of the survivors in the book do live in close proximity to their rapists, still. While one shares a wall with him, another lives in the same village (where no one came to her help during or after the rape). Yet another survivor lives in the same house as the man (her relative) accused of rape – and another, a young child, still plays on the same railway tracks near her home where she was hauled across, raped and left for dead. Can you imagine the utter horror and helplessness of that spatial discomfort?

These survivors do not have the resources or the infrastructure to physically upend their existence and find alternative living arrangements. They cannot abandon the little land they own or the slum settlement they currently occupy in the aftermath of a family member’s rape, needing to live, therefore, in an atmosphere of constant revulsion, anger and grief. And they shouldn’t have to. Nothing should make their safe space feel relinquishable – but it does.

That was a reality I confronted over and over again in my time as a journalist and friend with them. It humbled me to the endless, everyday infinitesimal realities that they must live with. I realised I could walk away if I wanted to. They couldn’t. I could wake up elsewhere, change my milieu out of active choice and not let geography dictate my mental or physical health. Not so, here.

One thing that I wanted to change through my reporting for this book was the “hierarchy” of reporting – the chain of merely visiting, sitting apart from the survivor and family, on surfaces and platforms that are far removed from them, conducting staccato, stiff one-on-ones and then, departing, offering them the idea of a detached outsider.

I didn’t want to sit on elevated platforms or chairs, where one’s case study usually offers you their one piece of furniture while they settle down on the floor and feel like they receive nothing in return. I wanted real, physical contact over days, months, years. Many, many phone calls. Many, many visits. Many, many offers of companionship to go to court, to make a call on their behalf, to translate documents.

It is not the same as living that reality – not even close. But I wanted to offer friendship beyond mere reporting, and, in the process, break the shackles of traditional reporting, constantly reinventing what interviewing survivors looked like.

In the process, I was changed – but that change is inevitable when you know someone intimately. I cannot imagine doing journalism any differently anymore. I want to go in thinking I’m going to change things today – or, at least, try my butt off.

As a reader, I certainly feel rage after reading these stories. But are the rape survivors themselves and their families and communities angry enough to fight back for years on end?

In my experience, the anger never dissipates – it is merely occluded by the lack of resources and the disillusionment with the system… Imagine fighting for years on end, taking that auto/bus/Metro ride to a sessions court every couple of months, showing up with a brave face to listen to your “character” get assassinated and make peace with the fact that that’s how things are, living in milieus that still remind you of the accused – if not physically, then culturally.

It would break anyone; yet, the survivors I spoke to for the book have continued this fight for years. Pia’s (the eight-year-old survivor's) mother keeps abreast of every change in the law, every development in a rape case, just to wonder how it will affect the case of her little girl.

Nidhi’s (the four-year-old's) mother is bewildered and oppressed by a system that conveys no information to her – she depends entirely on me to make calls, but fiercely protects her two girls’ right to education, telling them over and over again that there is no difference between them and a son. Neither Dalit woman is backing down.

When you’ve been pushed to the brink long enough, sometimes all thresholds break.

Are these cases taking so long in court because the judicial system is generally slow, or because these are ‘women’s issues’?

It’s obviously a bit of both, in a cycle. Rape happens because women are devalued and dehumanised in India. As a result, our judicial system is taxed – in fact, overtaxed. Official data from the country’s high courts (from 2019) show that 1,66,882 rape cases are pending trial – and, in fact, have a time lag of a little over a year. And this is official, recorded data – to say nothing of the cases that go unreported or are withdrawn before trial.

What will stop rape?

Number one? Teaching consent. Consent is not rocket science.

You’ve talked about the psychological impact of rape on the women. Do their families and communities understand their need for healing and do they make any efforts in that direction?

Ranjini was disbelieved by her husband who as good as said that she must have been in a relationship with her rapist – and had made up the story. Smita’s family didn’t understand for years; heck, she didn’t either, choosing to denigrate herself for loving the man who eventually raped her. She censures herself for a trope of a survivor she’s been told she doesn’t live up to.

These women do receive kindness and affection from their immediate family – their first support system – but what they need and what they don’t get, is solidarity. Solidarity against the crime and empathy for the many tiny ways in which they are changed.

Smita, now married, can no longer think of sex the same way. Nidhi’s mother does not trust the daughters beyond the parameters of the railway tracks where Nidhi plays (yet, it is next to the tracks that a man the family knew lured her and raped her and slashed her with a blade).

It is important to understand the ‘what-after-rape’ not only in the sense of a larger, cumulative healing but also the many ways that one cannot imagine they need to heal and unheal, recover and unlearn that recovering, every second of every day.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.