There’s a scene in Canadian-Pakistani writer-director Zarrar Kahn’s debut feature that feels straight out of Satyajit Ray’s Charulata (1964), young Mariam swings as Asad, besotted by her, lies on the grass. The short-lived felicity would soon turn nightmarish in the Pakistani horror thriller In Flames, which screened at the Director’s Fortnight at the 76th Cannes Film Festival last month. There, fanboy Kahn also met “Anurag (Kashyap) saab”. Once at a Karachi DVD house, Kahn recalls seeing 30 films’ cassettes titled Gangs of Wasseypur: Karachi. “GoW was really influential, it looked a lot like Karachi and spoke of similar themes. Anurag saab’s cinema influenced me a lot as a filmmaker, because it was arthouse, it was South Asian, and it was right now (contemporary), and made on a scale that felt within reach unlike a Karan Johar film, we don’t have billions of crores,” Kahn titters.

In Flames is the second Pakistani film in the Director’s Fortnight 43 years since Jamil Dehlavi’s Blood of Hussain (1980), starring Salmaan Peerzada, whose older self was seen last year in Saim Sadiq’s Joyland, the first Pakistani film in Un Certain Regard at Cannes festival, winning two awards. In Flames is yet another articulation of patriarchy, with added supernatural punch, spooks and jump scares.

“Watching his (Ray’s) films, along with (Bernardo) Bertolucci’s, helped me discover what’s in my mind,” says Kahn, “What he (Ray) was doing with his humanistic values, like one of the foundational films for me is The Big City (Mahanagar, 1963), which I remember watching and not understanding how this film was made and what it was saying about patriarchy when it was saying it, it’s incredible.”

Ramesha Nawal and Bakhtawar Mazhar in a still from the Cannes-premiered Pakistani horror thriller 'In Flames'. (Image courtesy Citylights Media)

Ramesha Nawal and Bakhtawar Mazhar in a still from the Cannes-premiered Pakistani horror thriller 'In Flames'. (Image courtesy Citylights Media)

In In Flames, Mariam (Ramesha Nawal), 24, is studying to become a doctor. Her unsuspecting, widowed schoolteacher-mother Fariha (Bakhtawar Mazhar) gets taken in by uncle Nasir’s (veteran actor Adnan Shah Tipu) cunning niceties after the death of her patriarch-police-officer grandfather. Mariam grows up around predatory men. Strangers attack her car, masturbate outside her balcony, faith healers cross a line, benevolent acts are never not malevolent. Canada-returned Asad (Omar Javaid) is the sole breath of fresh air, albeit short-lived. Kahn fleshed out his Locarno-premiered 24-minute short film Dia (2018), drawing Bakhtawar and “themes of grief, womanhood, family” into this feature. If the short became a thriller fortuitously, horror-thriller was the chassis for In Flames.

Genre cinema

One wonders, had Sadiq’s Joyland not been a social-family-queer drama would it have faced the kind of backlash, trolling, ban it did? “It was banned in the more difficult markets of Punjab and the federal, not in the Sindh province”, Karachi falls in Sindh and that gives hope to Kahn’s crew. “The genre lens will allow us to be able to say things that are more difficult to say through a social-issue film,” says Kahn, “it will give accessibility to those who don’t have that experience to understand what it’s like.”

Genre films also, often, gives “the protagonist more agency, allowing them to defeat their demons/antagonist, to overcome all odds versus social-issue dramas which reflect the real world in all its complexity. I don’t engage with poverty porn, for instance, where you see a terrible world with terrible characters, if I’m in that world, I’ll need cinema to inspire me to continue going, that’s what this art form can do,” he adds.

“I liked what the classic filmmakers (Ray, Bertolucci) were doing with the tools in their time, and, right now, our classic filmmakers are genre filmmakers, who are pushing the medium forward,” he says, mentioning Jordan Peele, Julia Ducarnou, Mati Diop, who are using genre “in inventive ways to amplify voices from underrepresented communities.” So does Kahn, who spotlights Karachi’s Goan Christian community in the short film 1978 (2020).

Pakistani renaissance

Pakistani-Canadian director Zarrar Kahn during the shoot of 'In Flames' in Karachi. (Image courtesy Citylights Media)

Pakistani-Canadian director Zarrar Kahn during the shoot of 'In Flames' in Karachi. (Image courtesy Citylights Media)

Storytelling was the soundtrack of Kahn’s childhood, who’d be consumed by the world of comic books, as his Montessori teacher-mum watched Kajol’s films on the tele on Sundays. Kahn, aged 10, moved to Canada with his family, and returned to Karachi in his teens. He set up the theatre company Citylights, which co-produced his film. Short films took the un-film-schooled Kahn to global festivals. He’s grateful to two mentors: Pakistani-American filmmaker Iram Parveen Bilal’s screenplay writers’ programme Qalambaaz and “Indonesia’s Tarantino”, the Satay Western filmmaker Mouly Surya, at Busan’s Asian Film Academy.

“Our main industry is Pakistani dramas (television), whose production standard doesn’t work for cinema or commercials, which is where the incredible technicians are, but they wouldn’t work on your independent film for 1/10th of what they would get otherwise,” says Kahn.

The Pakistani renaissance happening now harks back to an older time. “For me, it was him (Jamil Dehlavi),” says Kahn. The Blood of Hussain (now on YouTube) was banned in General Zia-ruled Pakistan. “The few independent, arthouse Pakistani filmmakers in the ’70s couldn’t sustain given the lack of an industry/industry support,” adds Kahn, “Now, many short films emerging out of Pakistan are travelling to festivals; so, despite no institutional support, there’s the internet, accessibility, and tools are cheaper…this time, it’s different.”

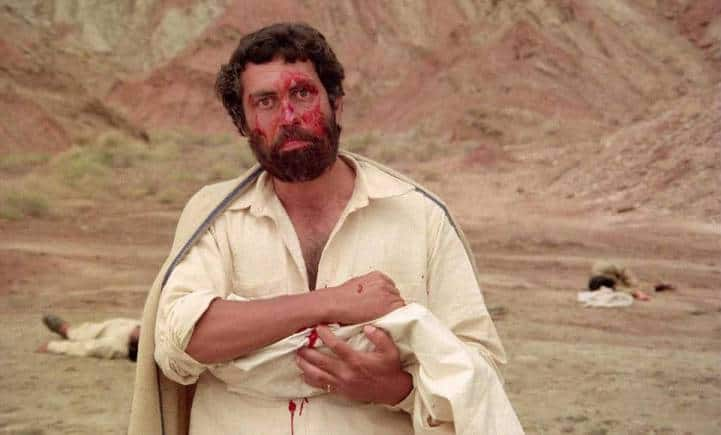

A still from Jamil Dehlavi's Cannes-premiered 'The Blood of Hussain' (1980).

A still from Jamil Dehlavi's Cannes-premiered 'The Blood of Hussain' (1980).

There’s a striking thematic and locational similitude in In Flames and Mati Diop’s Atlantique (2019) and early Senegalese cinema. “Pakistan’s commercial films don’t reflect what it’s like to live here, what the city looks like. Karachi is a Muslim city; it’s a hot city. When I looked at Dakar, at films like Touki Bouki (Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Journey of the Hyena, 1973) and Atlantique, the bougainvillea in that city across many oceans looked just like it is here, them celebrating Eid-ul-fitr was just like we do it in Karachi city. So, I had to cast a wider net for my influences since we don’t have this rich history of cinema in Pakistani industry,” he says.

Lights, camera, sound

Kahn deftly locates the universal in the local, exteriorising the internal. In Flames is tactile and visceral and transports you to the city, to its colours and textures. Three principal colours stand out the way colours do, say, in an Abbas Kiarostami film. “In Karachi, neon green, pink, and orange are everywhere. At nighttime, there’s neon green sparkly lights. Green is also the colour of Islam and is prevalent throughout the city.”

Kazakhstani DOP Aigul Nurbulatova’s camera hovers over the city and the two main characters, like a surveillance tool, like the vultures/black kites seen in aerial shots, like a Panopticon patriarchal state, amplifying the eerie claustrophobia closing in on the women. Two shots stand out. A dream sequence, where Mariam steps out of her red-gold-wallpapered bedroom onto the beach. It was inspired from a Canadian feminist film, The Last Mermaid. A similar scene done differently, where the character escapes the drudgery of urban experience into a dream world. “In Mariam’s case, it felt like a nightmare. This young woman is losing her way, her grip on reality,” says Kahn.

The other is the climactic scene, masterfully mounted, it encapsulates the whole story. In single frames, Kahn uses both warm and cool tones, culminating on a high-contrast lighting crescendo. The camera follows the flames up from a burning beach-hut (built by production designer Matti Mallik). The camera stays static as the sky turns into the road, and at the bottom of the screen a car emerges from the flames. These women, driving out of the fire, are reborn having overcome an impossible problem.

Commanding equal attention is the inventive sound design, which “stemmed from the sounds of the city”. The recurring calls of the birds of prey cheels (black kites) and the sound of a wooden/metal stick tapping the ground, a familiar sound that chowkidars (street guards) make while patrolling South Asian neighbourhoods to signal the area is safe. Toronto-based sound designer Bret Killoran takes this sound of safety and distorts it to signal a sound of danger, “safe does not exist” in the characters’ world. The diegetic sound of horror/fear becomes internal. The sensorium of danger is further compounded by the sounds of wind chimes — that Sri Lankan-origin Canadian composer Kalaisan Kalaichelvan carried with him from Indian temples into the background score — and a groaning metallic construction sound, as if the Earth’s crying.

Simultaneously, “a tapestry of Pakistani music” is embedded into the film. The soundtrack of young Mariam falling in love comprise swing sounds and upbeat pop. “Pakistan has always loved pop music, we had Nazia Hassan in the ’70s. Right now, we have incredible young talent creating pop music, climbing global charts.” Lahore artiste and one half of the band Biryani Brothers, Natasha Noorani (the Faltu pyar girl) came aboard. “There’s a lot of other music, the Sindh-popular been (snake-charmer’s instrument), a Balochi artiste’s music which traces its roots to Swahili music” and Karachi musician Clifford Lucas’ song from Kahn’s 1978 resurfaces as well.

A star is born

'In Flames' actor Ramesha Nawal at Festival de Cannes last month. (Photo: Stephanie Cornfield)

'In Flames' actor Ramesha Nawal at Festival de Cannes last month. (Photo: Stephanie Cornfield)

If Bakhtwar channels her inner South Asian mother to a fare-thee-well, the theatre-trained Ramesha, a fairly last-minute cast replacement, shines in her first time on camera. Not a single note and expression is off-key, she delivers a power-packed performance with great restraint. Both the women are indomitable and yet vulnerable. “A quiet presence in real life, Ramesha transforms as soon as the camera’s on her. A lot of Mariam’s experiences spoke to Ramesha’s own: growing up in Karachi with the baggage/weight of an eldest daughter. I’d give her the character’s backstory, emotional beats, strongest motivation, and her raw instincts would be spot on. They say directing is like 90 per cent casting and this felt like that,” Kahn says.

Mariam wears the hijab, drives a car, listens to pop music, is studying to be a doctor — “these are normal things in urban middle-class Pakistani society, the real risk she takes is in falling in love” — she’s plucky enough to bear the untoward consequences.

Ramesha Nawal in a still from 'In Flames'.

Ramesha Nawal in a still from 'In Flames'.

Mariam is every South Asian woman — a sweet amalgam of the traditional and modern. “In Pakistan, you grow up with religion, many close to me are both extremely modern and deeply religious. Mariam is straddling the line of complexity of that identity,” says Kahn as Anam Abbas, the film’s co-producer and Karachi-based documentary filmmaker, quips, “I cover my head, I’m a religious person, and I’m in this (film) industry. The contradictions are from outside rather than inside, that if you wear a hijab, you must be submissive. Those of us who find comfort or pleasure in our religious behaviours or associations are able to keep that internal, and have the agency to be able to live our lives. That’s what feminism is for us, to be able to make our own rules, choose our own paths.”

What women of Pakistan want

“It is a society that, as Anam says, is violent in many ways, in terms of its response towards feminism…the conflict that’s happening with Aurat March. Power never wants to give away its power. That’s why we want to make this film to speak about the importance of resistance,” says Kahn.

Zarrar Kahn instructing Ramesha Nawal's Mariam during the shoot of 'In Flames' in Karachi. (Image courtesy Citylights Media)

Zarrar Kahn instructing Ramesha Nawal's Mariam during the shoot of 'In Flames' in Karachi. (Image courtesy Citylights Media)

The annual Aurat March, which Abbas follows in her documentary This Stained Dawn/Dagh Dagh Ujala (2021), “grew rapidly from three cities in 2018 to 11 cities in 2019. The second year was when the backlash started, and it has continued, but the marches also continue. If Sindh government is supportive, the march in Islamabad has been attacked twice, it’s definitely something that ruffles feathers. It’s a very large movement that has changed the language of how this country (Pakistan) speaks about women’s issues,” says Abbas.

Mariam’s post-traumatic guilt reappears as ghosts. Fresh trauma unearths a past she’s tried to bury. In Flames is about a mother and daughter bonding over a generational trauma and overcoming it together — the need for community action to redress individual problems makes the film at once a feminist film and a film about hope.

Patriarchy affects all genders, Kahn concurs, “the way they interact, the public space, the public discourse.” Not just in South Asia but across the world, “with abortion rights being rolled back in America; what’s happening in Iran; we’re in this time of conflict, time of flux, and, so, it felt urgent to make In Flames right now,” he says.

Further adding, “In the globally capitalistic world we live in, power comes from money. In South Asia, as in many societies across the world, money comes from property. By restricting a woman’s right to property, you’re restricting power, autonomy, agency. And that’s done in such an insidious manner in Pakistani society, because in Islam, women’s property rights are part of the religion, they are written into the book, but that’s also exploited in our patriarchal culture where even those rights are not given. So, I wanted to speak to the institutional ways that oppression works along with the fantastical.” Weaving the legal tussle into a gender’s timeworn social struggle adds heft to the narrative.

“The laws are there in Pakistan, although the State has tried to roll it back, like they recently rolled back the progressive trans laws. It’s the implementation. Courthouses, police offices are not women-friendly spaces; women avoid them for the fear of being dismissed,” adds Abbas, the daughter of a single mother who’s faced it at close quarters. “Economic power is your real power. Every woman is dealing with property rights, it’s an issue that cuts across class and political leanings,” she says, adding that even the most right-wing, anti-feminist women concede that they have to fight for property rights, which is often seen as a sign of “not loving your brothers”.

“The very act of living in countries like ours is a political act,” adds Kahn, in whose films the realpolitik is always a subtext. In In Flames too, at three spatiotemporal junctures, three different party flags are positioned. “When you live in Karachi, politics is tied to your experience. In Pakistan, as it is in India, a flag is the image of your identity, but it’s also the image of where the city is at that moment in time. I wanted to root the film and the characters in the disparate politics around them that they’re always aware of, but they’re dealing with so much of their own baggage that they’re not engaging with,” he says.

Across the border

A new crop of Pakistani filmmakers like Sadiq and Kahn are internalising the critical gaze and sensitively filming how social violence cage women, while across the border, some male filmmakers are co-opting and encashing historical violence against women to fill their coffers and feed into a propaganda to incriminate a religious-minority community. The trend is “regressive”, says Shant Joshi, of Fae Pictures, the OCI (Overseas Citizen of India)-Canadian producer on In Flames.

These films “break the idealised version of India that Bollywood had built for so long. In the ’70s, it showed a version of India, of a democracy, where people come together, and now we’re looking at a very different type of extreme Indian cinema coming out,” says Kahn, who’s made films on Pakistan’s creeping fascism and dictatorship of 40 years ago. From an “outsider’s perspective”, he adds, “it feels like what happened in the ’70s in Pakistan is happening right now in India, I hope it doesn’t end up like it did for us.”

Way forward: Diaspora producers

(From left) Co-producer Anam Abbas, actors Mohammad Ali Hashmi, Omar Javaid, Ramesha Nawal, Pakistani-Canadian director Zarrar Kahn, actors Bakhtawar Mazhar, Adnan Shah Tipu, Indian-Canadian co-producer Shant Joshi of Fae Pictures. (Photo: Delphine Pincet)

(From left) Co-producer Anam Abbas, actors Mohammad Ali Hashmi, Omar Javaid, Ramesha Nawal, Pakistani-Canadian director Zarrar Kahn, actors Bakhtawar Mazhar, Adnan Shah Tipu, Indian-Canadian co-producer Shant Joshi of Fae Pictures. (Photo: Delphine Pincet)

With widening political gaps, trade and art bans between the neighbours, the only way to work together creatively, perhaps, is through collaborations of their diaspora. India’s Los Angeles-based Apoorva Guru Charan was a co-producer on Sadiq’s Joyland, and Toronto-based Joshi, who was once setting up a project with Onir, found Kahn’s film at the 2020 Berlinale Talents Project Market. “Our (Fae Pictures’) slate of projects encompasses a more global decolonial perspective. The reason to back Kahn/In Flames was because it is decolonial. I work with a lot of Pakistani creatives. And with what was happening with CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act), NRC (National Register of Citizens), the student protests back in 2020, it made total sense to collaborate with Pakistan,” says Joshi.

“Diaspora audiences, producers and production houses have a more active role to play in the content coming out of South Asia because they can navigate outside border restrictions in an increasingly difficult world,” says Kahn, as Abbas adds, “(International Emmy Award-winning producer) Apoorva Bakshi, who’s the producer on (Netflix series) Delhi Crime, has just joined (Usman Riaz’s) The Glassworker, a Pakistani hand-drawn (Hayao Miyazaki-styled) animated film, which has been in the works for many years, so, it’s already happening.”

ALSO READ: The rise of Manipur, women, cinema: Ishanou & documentary on Aribam Syam Sharma at Cannes 2023

ALSO READ: Cannes 2023: How Suzlon, COVID & menstrual taboo served this Kolkata boy a female story

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.