The Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) crisis may now be passé but to the question as to how banks in India escaped the impact, we often point to their resilience and rule-based regulation that insulated them from global events. This is hard to refute, but there are some nuances to the crisis which relate to how banking works in India and the US. One, banks in the US have long moved away from traditional lending to investment, originate-to-distribute lending models and non-fund activities in their quest for higher returns. Indian banks have mostly stuck to the well-trodden path. Two, even as US banks grew non-traditionally, deposits were still their mainstay, which made them more vulnerable than when they were traditional banks.

The risk came from both sides of the balance sheets – flighty deposits and asset portfolios that were constantly revalued. Changes tended to get transmitted quickly through the stock and other asset markets adding to their vulnerability; a short seller in a bank stock, for instance, could trigger a run. Indian banks enjoyed some important differences that made them less vulnerable.

Staying Traditional Helps

Even though its lending avenues had declined, SVB chased deposits

especially zero-interest accounts which had grown too rapidly for comfort. Its loan-to-deposit ratio was just 43 percent as it locked up the rest in long-dated securities. But with over 80 percent of its deposits repayable on demand, and by not hedging interest risk, SVB was betting on interest rates not climbing much or depositors not pulling back all at once. Neither happened and the losses it booked when it sold securities to repay deposits eroded its regulatory capital, triggering its stock to plunge and causing a run on its deposits. Chasing deposits to invest them principally in market securities was not banking as one knew it. The model failed them and a few other smaller regional banks. They were also said to be inadequately supervised, but in the end, what mattered was how depositors perceived them.

In contrast, Indian banks continue to be bastions of traditional intermediation and maturity transformation with a high credit-deposit ratio (76 percent). The flip side was higher non-performing loans, but that did not impact valuations or perceptions of safety much as transmission mechanisms (securitised loans market) were either weak or non-existent. Regulatory forbearance also played a huge part. Some of the onerous reforms like a few of the Basel-3 requirements, expected loss-based provisioning, disclosure of interest rate risk in bank book, and minimum capital requirements for market risk were kept in abeyance. But most importantly, government ownership of a predominant chunk of banking, acted as an implicit guarantee even as official deposit insurance remained low like in the US. That perhaps explains why, despite high NPAs and scams, there have been no major bank runs, except calibrated closures initiated by the regulator to pre-empt possible runs.

Safety in Government Bonds

The contrast is also visible in investments. Over 80 percent of Indian banks’ investment portfolio consist of government securities, driven either by statute (statutory liquidity ratio, liquidity requirements) or by risk aversion (regulatory forbearance again, which assigns zero risk to government securities); in the US, securitised credit forms a significant chunk of bank credit (mortgage-backed securities, securitised consumer credit), which means banks face not only credit risk but market and interest rate risks as well.

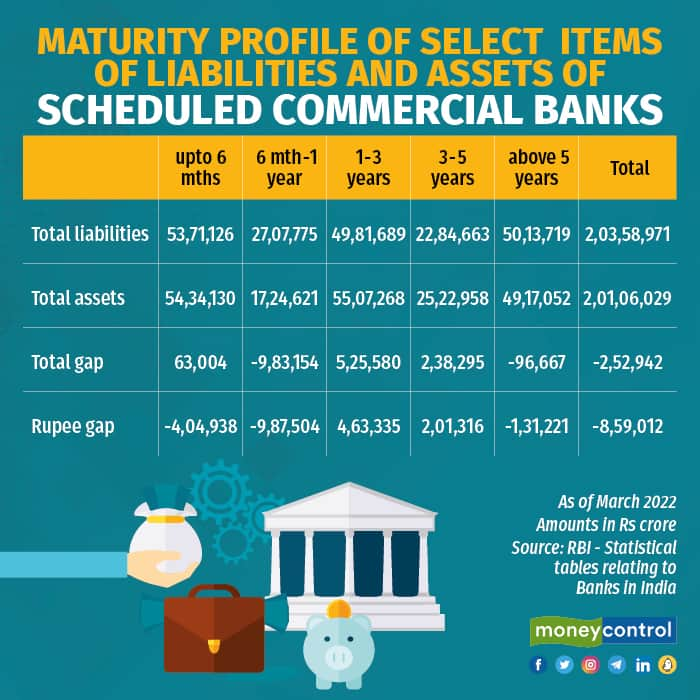

At the micro level too, there are key differences in funding and cash flow profiles. Thus, even as problems such as asset-liability mismatches or bad debts remained the same, banks were less vulnerable. For instance, Indian banks also face large asset-liability mismatches, which may not be so well known.

As can be seen from the graphic, except in the middle buckets (1-5 years), banks have large liquidity gaps, in rupee terms. This is not surprising given the high current account and savings accounts (CASA) ratio of 44 percent and the limited short-term lending and investing. But mismatches did not cause any major issues which has to do with the nature of the liabilities.

Nearly all of SVB’s deposits came from a homogenous depositor class (venture funds, tech start-ups) while CASA deposits of Indian banks are diversely owned (retail individuals 65 percent and the rest by government, corporates and others). More importantly, these deposits flow from the transaction demand for money (payments). The spectacular growth in UPI transactions from Rs 8 lakh crore in 2019 to over Rs 80 lakh crore by 2022 could be a factor in the rapid growth of CASA deposits. Being less sensitive to interest rate movements, these deposits have become a reliable and consistent source for banks, unlike the US where the proportion of non-interest-bearing deposits is smaller.

Traditional banking, the play of forbearance, funding and cash flow characteristics, all combine to make Indian banks less vulnerable than their US counterparts. A former governor once termed Indian banking as a grand bargain, where in return for low-cost funds and safety, banks agreed to invest in government securities and lend to priority sectors. The true test of resilience will perhaps be when there is greater privatisation, lesser forbearance and more market reforms.

SA Raghu is a columnist who writes on economics, banking and finance. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.