For the Indian economy, it's like a shift from the frying pan to fire.

As 2022 draws to a close, the economy's old challenges starts giving way to new ones. Inflation has cooled off remarkably in the recent months, the government's finances are evolving broadly as expected, and the demand for loans is growing at the fastest clip in several years.

The new year will see the government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) grappling with new forces. These forces, while not unknown, will certainly lead to pressures that do not have text-book solutions.

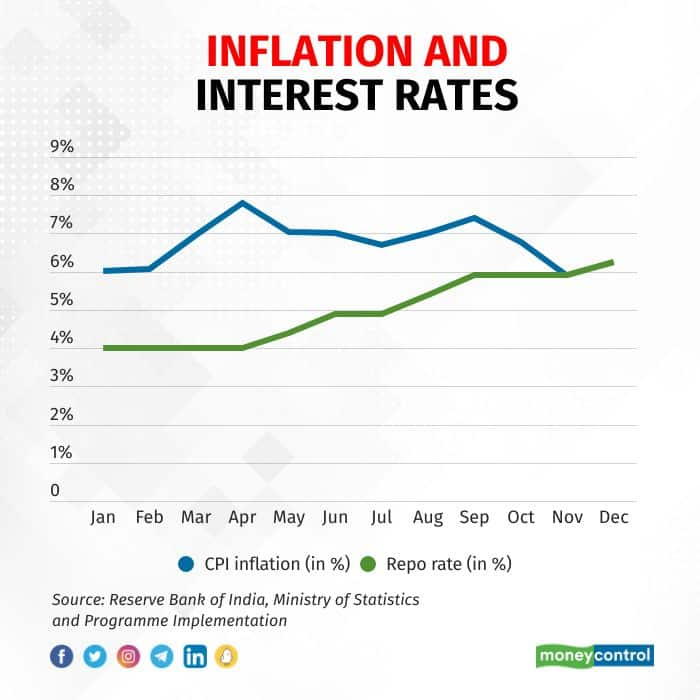

Tackling inflation was perhaps the number one on the policymakers' list of challenges in 2022. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation started the year by exiting the RBI's tolerance band of 2-6 percent. By the time the CPI data for September was released in October, the central bank had failed to meet its mandate, forcing it to submit a report to the government on the same.

Having faced the accusations of being behind the curve, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the RBI finally began hiking the policy repo rate in May. Earlier on December 7, the panel announced its fifth rate hike of the year, taking the total quantum to 225 basis points.

One basis point is one hundredth of a percentage point.

But the larger-than-expected fall in inflation to 5.88 percent in November has almost sounded the end of the tightening cycle, with Soumya Kanti Ghosh, State Bank of India's group chief economic advisor, assigning a "minimal probability" of the MPC raising the repo rate by 25 basis points to 6.5 percent in February.

The positivity from the latest inflation number has been such that economists have sharply lowered their forecasts. Deutsche Bank, for instance, now sees the average inflation for 2023-24 at 5 percent – a full 50 basis points from what it had expected previously.

Return of rate cuts?

If the end of the RBI's rate hike cycle is in sight, its partial reversal may not be far away either.

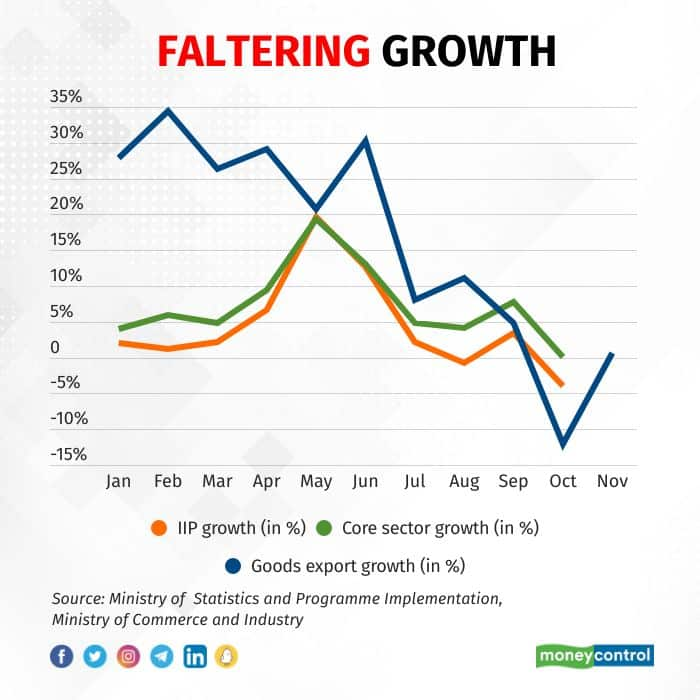

A lower base has helped India post impressive growth rates in the recent quarters - 13.5 percent in April-June and 6.3 percent in July-September. However, the pace of growth is now expected to slow down, with the RBI forecasting a GDP growth rate of 4.4 percent for the last quarter of 2022 and 4.2 percent for the first quarter of 2023.

Moreover, the rapid and synchronised tightening of the monetary policy is likely to slow global growth down further. The effect on India is visible now: merchandise exports fell by 12 percent on a year-on-year basis in October before rising by less than 1 percent in November.

According to Nomura, India's growth rate cycle has already peaked, and the GDP growth may slump to just 4.5 percent in 2023 from its expectation of 6.7 percent in 2022. This, according to Nomura, will force the RBI to cut the repo rate multiple times in the second half of next year.

"In 2023, we expect a global growth slump to play an outsized role in influencing domestic growth, with exports likely to fall precipitously, especially through January-June, when the global hit will likely be most severe," Nomura economists said in their outlook for 2023 this month.

"The private capex upcycle has remained lacklustre, while global uncertainty and tighter financial conditions are likely to weigh on corporate investment plans, resulting in weaker fixed investment growth."

Green shoot

The one beacon of hope the authorities have been keen to point out at every opportunity is growth in bank credit.

Having spent years in the rut, credit growth took off in 2022 and is approaching 20 percent.

"While in absolute terms, the overall real growth recovery is still a work in progress, the type of recovery is working in favour of credit growth," Gaura Sen Gupta, IDFC First Bank's India economist, said in a report last month.

"After the pandemic, a K-shaped recovery is underway where urban demand is seeing a stronger recovery than rural demand… This differentiated pace of recovery is also showing-up in credit growth with loan growth led by metropolitan and urban areas, which account for nearly 80 percent share in bank credit. Meanwhile, the pick-up in loan growth in rural areas is more muted," Sen Gupta added.

The rapid rise in credit growth in 2022 has come despite banks increasing their lending rates. As per the latest RBI data, the weighted average lending rate on new loans was 117 basis points higher in October, compared to April – before the central bank started hiking the policy rate.

However, Sen Gupta pointed out that bounce rates of EMI auto-debits are currently the lowest in three-and-a-half years, suggesting that demand for loans "is likely to hold-up despite higher interest costs".

As we enter the New Year, all eyes will turn to the Union Budget for 2023-24, to be tabled on February 1. The Centre may continue with its capex push. However, fiscal consolidation will not be far behind. Or, at least, it shouldn't be.

Lowering the fiscal deficit from 9 percent-plus to mid 6-percent was the easy part, helped in no small measure by a huge jump in nominal GDP. The next financial year is set to see a much lower nominal GDP growth of under 10 percent, according to economists, resulting in reduced tax buoyancy.

"The Budget needs to focus on a number of sectors which still require handholding and support, while at the same time managing fiscal consolidation," said Radhika Pandey, Senior Fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

"There is a tightrope walk required between supporting some sectors, continuing with frontloading capital expenditure, and managing fiscal constraints. This is a challenge because 2023 is going to be a difficult year," Pandey said.

Over the last two-and-a-half years, Governor Shaktikanta Das' monetary policy addresses have been sprinkled with inspiring quotes. From the look of things, they will be needed next year too.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!