The global economy lost steam in 2018 after a synchronized recovery in 2017 and a sluggish growth phase during 2012-16, leading to a broad-based slowdown in the first half of 2019. With escalation in US-China trade tension and growing economic policy uncertainty as a result, global trade, exports, manufacturing and investment activity have been severely impacted.

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates, trade volume growth in the first half of 2019 came in at 1 percent -- the weakest since 2012 -- as the tariff war intensified, disrupting globally integrated supply chains centred around the Chinese manufacturing sector.

Going by data of the Peterson Institute on International Economics, average US tariff on Chinese imports has increased to above 26 percent compared to an average 3 percent at the beginning of the trade war. Similarly, China’s average tariff on US exports have gone up to 21.8 percent from the earlier 8 percent.

Even as manufacturing has been hit by the elevated trade barriers, services and consumer spending have been relatively resilient, especially in the US. Taking note of these developments, the IMF in its October World Economic Outlook review downgraded its forecast for 2019 global growth to 3 percent -- its slowest pace since 2008 -- and is projecting a shallow recovery in 2020 with elevated downside risks.

The latest Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) forecasts are gloomier, with global growth seen at 2.9 percent this year and the next, with a marginal improvement in 2021, as investments are being held back due to worries about economic uncertainty and the trade dynamics.

Falling off the cliff

Among major global economies, China has seen its GDP growth slip to a 30-year low of 6 percent in Q3, as rising US trade tariffs have led to a contraction in Chinese exports as well as imports. As a result, manufacturing activity has been consistently weak since the third quarter of 2018. The non-manufacturing sector, which was performing better, has lost steam too during Q3 2019.

Retail sales growth, a measure of consumption, has dipped to a 16-year low. Fixed asset investment growth fell to 5.2 percent in October, its lowest level in two decades, as Chinese policymakers are focusing on reducing debt levels, which as per the latest estimates of the Institute of International Finance (IIF) have touched 306 percent of GDP.

Considering that the Chinese economy contributes almost a third of global growth, a slowdown has had a wider impact, especially on countries like South Korea and Australia, which are heavily dependent on Chinese imports for their growth. In fact, some of the biggest downward revisions for growth forecasts by the IMF are for economies in Asia like Hong Kong, Singapore and Korea, given their exposure to a slowing growth in China and spill-overs from US-China trade tensions.

Weak economic activity in Euro-zone

With large exports and industrial base, Eurozone’s largest economy Germany has only narrowly missed a recession in 2019. Its economy is witnessing an acute downturn in the industrial sector, along with weak exports growth, led by a contraction in global auto sales and a slowing global trade. Industrial output has contracted since August 2018, and this period of contraction has extended to September 2019. Exports growth has slowed too, with an average growth of 0.5 percent in the first eight months of 2019, after registering 3 percent expansion in 2018.

The composite PMI data in October showed that non-farm activity remained in the contraction zone. For the Eurozone as a whole, industrial production is contracting and GDP growth has slowed sharply to 1.2 percent in Q2 2019, from 2.6 percent in Q1 2018. German GDP growth deceleration has been more pronounced at 0.4 percent in H1 2019, from 1.5 percent in 2018.

US growth prospects clouded by uncertainty

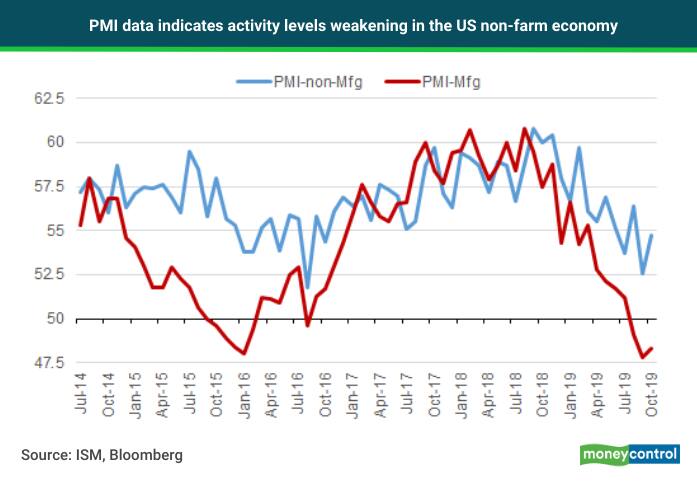

The US economy is the only large economy where growth is reasonably strong and the IMF growth forecast cut is small in magnitude. It is witnessing its longest phase of economic expansion on record, now in its 11th year. Real GDP growth so far this year has averaged at 2.4 percent, somewhat slower than 2.9 percent in 2018.

Growth has been supported by a strong household consumption, which in turn has been driven by a thriving labour market. Unemployment rate is near a 50-year low, real wages are rising and labour force participation rate is picking up. However, slower global growth since the middle of 2018 and increased uncertainty around the trade policy have slowed down manufacturing activity and investment spending. And with the effect of tax stimulus running out in 2020, the US yield curve has been at various points this year signalled a risk of recession by 2021.

Looser monetary policy to the rescue

In response to this synchronized slowdown, central banks of economies constituting 70 percent of global GDP have simultaneously eased monetary policy. Absence of inflationary pressures, particularly from oil, has provided them the space to do so. The most notable change has been in the US Federal Reserve’s policy actions.

At the beginning of 2019, the Fed was poised to continue normalising monetary policy by raising rates. However, in order to counter the spill-over risks from slower global growth, the Fed has gone for a mid-cycle adjustment and has cut the Fed funds rate by a cumulative 0.75 percent instead and has resumed balance sheet expansion to meet the liquidity needs of the US financial system. The European Central Bank too has eased its monetary levers further and has resumed quantitative easing.

Chinese policymakers, however, have shown restraint in providing a large stimulus to the economy and focussed on tax reforms. Monetary stimulus has been limited in comparison to the previous episodes of slowdown like in 2008 or 2015, in order to avoid reflating a debt bubble.

The IMF estimates that in the absence of such monetary stimulus, global growth would have been lower by 0.5 percent in both 2019 and 2020. This global policy stimulus has helped offset the negative impact of the US-China trade actions, which are estimated to cumulatively reduce the level of global GDP in 2020 by 0.8 percent.

Fear of a debt bubble

The latest Global Financial Stability report of the IMF, however, warns of persistently low interest rates encouraging financial-risk taking in search of yield and fuelling a further build-up of financial vulnerabilities in some countries and sectors due to rising debt burden. Market yields have declined sharply, with $15 trillion worth now trading at negative yields and global investors now expect interest rates to remain very low for long.

Low rates have been encouraging a build-up of debt, across borrowers, especially with those with weak servicing capacity. As per latest estimates by IIF, global debt crossed all-time high above $250 trillion or 240 percent of world output during the first half of 2019, with China and US accounting for 60 percent of the new borrowing.

A major driver of the debt build-up is private sector borrowings, which make up almost two-thirds of total debt. Further, the amount of dollar denominated debt issued in emerging markets has gone up sharply in recent years. Non-financial sector borrowers in emerging markets other than China, have increased their foreign currency debt, by more than 20 percent of GDP by the end of Q2 2019.

Any tightening of financial conditions on global risk aversion or further strengthening of the dollar could make servicing this debt more difficult and that remains a key medium-term risk for the global economy. For emerging markets, especially in Asia, any persistent weakness in the Chinese Yuan, which is currently close to an 11-year low, is another risk, which could bring their currencies under pressure.

Stimulus the way out?

Given the downside risks to global growth against the backdrop of uncertainty around the trade policy and already low rates, calls for fiscal stimulus for ensuring a global recovery are growing, especially in countries like Germany, where sovereign borrowing rates are negative and budget in surplus. The OECD has recommended that advanced economies should kick-start bold public investments to support private investment in new energy technologies. The IMF, too, is urging economies with fiscal space to provide stimulus to avoid a long period of stagnation.

The year, however, is ending with asset markets turning more positive about the prospects of an economic recovery next year, following favourable developments around trade, which the US and China are looking to sign as a Phase 1 deal on trade. The next round of US tariffs comes into force on December 15, post which 97 percent of Chinese imports will be covered. The US administration has also delayed imposing tariffs on auto imports from the EU. However, considerable uncertainty persists around trade negotiations ahead of US Presidential elections in 2020 and that remains a major risk.

Where does India stand?

The global backdrop will continue to be a headwind for the Indian economy, which is already grappling with weak domestic demand, poor consumer and business sentiment, lenders’ risk aversion and falling bank credit growth, credit squeeze from the NBFC (non-banking financial company) sector and sector-specific challenges impeding investments.

Growth slipped to a 6-year low in Q1 FY20 and is likely to print below 5 percent in Q2 and around 5.3 percent for the whole of FY20, which is well below the potential growth rate of 6.5-7 percent. Monetary policy has stepped up stimulus to deal with this cyclical slowdown, but rising headline inflation may limit the easing space going forward, even as the policy remains accommodative.

Sector-specific measures to help real estate, telecom, auto and those aimed at increasing bank credit flow, especially to MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises), have been taken. A discretionary fiscal measure in the form of a corporate tax cut to kick-start investment has also been undertaken. At this stage though, the need for deleveraging would take precedence over fresh investments by the corporate sector.

Counter cyclical fiscal stimulus is still required, even as automatic stabilisers in the form of lower tax collections versus the Budget estimates, especially in the case of the GST (goods and services tax), have already kicked in. Other fiscal measures, particularly rationalisation of personal income taxes to support demand, along with stepping up public investments, will be required. One finding of a new NIPFP (National Institute of Public Finance and Policy) shows that demerit subsides at the general government level are still high at around 5.7 percent of GDP.

Further subsidy rationalisation can thus provide the fiscal space, especially at the state government level, for supporting growth. An expansionary fiscal policy, within the space provided under the revised FRBM (Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management) rules, should be used to buttress other policy measures to kick-start growth and improve sentiment.

Countering the private demand slowdown and a weak sentiment is crucial. Otherwise, even a modest economic recovery could take longer than another 3-4 quarters, especially if the global risks escalate and trigger investor risk aversion.

Gaurav Kapur is the chief economist of IndusInd Bank. Views are personal.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.