"I would like to emphatically reiterate that our inflation target is 4 percent and not 2-6 percent."

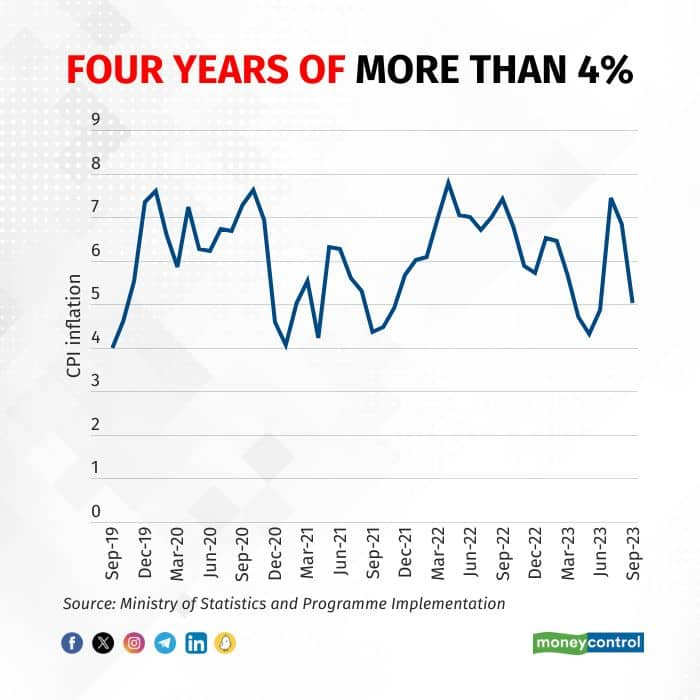

When it comes to reminders, Reserve Bank of India governor Shaktikanta Das spelling out the central bank's target on October 6 was both opportune and ironic – because the statistics ministry confirmed less than a week later that headline retail inflation had completed four full years above the medium-target of 4 percent.

Also Read: RBI doubles down to ward off complacency as long rate pause gets longerIndia's flexible inflation targeting, or FIT, framework was formally adopted by the government and the RBI in August 2016. And Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has been above the 4 percent target for more than half of the framework's life.

Of course, there have been mitigating circumstances: a once-in-a-century pandemic followed by a war and almost-constant geopolitical tensions. But the law is the law, and the law must be followed.

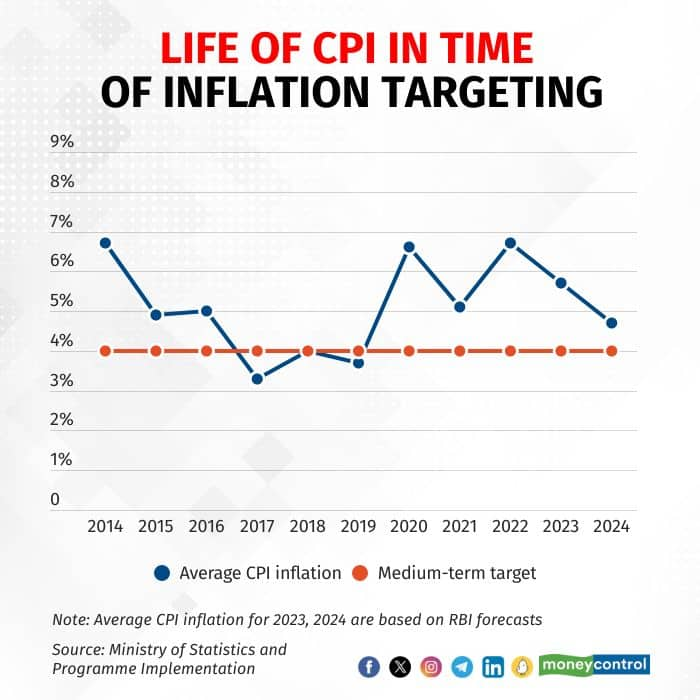

Success yearsThe FIT framework essentially became the RBI's operating target in January 2014 after then governor Raghuram Rajan accepted the recommendation of the Urjit Patel committee to revise and strengthen the monetary policy framework to reduce CPI inflation – shifting the central bank's focus from Wholesale Price Index (WPI) inflation – to 8 percent by January 2015 and then to 6 percent by January 2016.

Also Read: RBI staff see India soon entering a 'low inflation regime'One year later, in February 2015, the government and the RBI signed an agreement codifying the glidepath and a 4 percent target for the medium term. This was notified as law in August 2016, a month when CPI inflation slowed to 5.05 percent. Clearly, the fruits of the FIT framework were visible even before the law came into effect, thanks in no small part to cooling global crude oil prices.

But such was the success that average CPI inflation eased from 6.7 percent in 2014 to 3.3 percent, 4.0 percent, and 3.7 percent in the three years starting 2017.

Equally importantly – because growth, too, is part of the RBI's mandate – monetary policy did not become tighter.

"We do not find that the RBI became more hawkish following the transition to IT (inflation targeting); to the contrary, adjusting for inflation and the output gap, policy rates became lower, not higher," an October 2020 paper by economists Barry Eichengreen, Poonam Gupta, and Rishabh Choudhary concluded.

Pandemic shockWhile COVID undeniably pushed up inflation, it had shot up even before supply restrictions caused by global and nationwide lockdowns came into effect. CPI inflation surged from 3.99 percent in September 2019 – the last time it was below 4 percent – to 4.62 percent, 5.54 percent, and 7.35 percent in the final three months of 2019 before starting 2020 at 7.59 percent on the back of soaring vegetable prices.

In December 2020, inflation for tomato, potato, and onion was 35 percent, 38 percent, and 327 percent, respectively.

But the pandemic ensured inflation stayed elevated, pushing it up to 6.6 percent in 2020, almost 300 basis points higher than the average for 2019. This was after initial expectations were that lower demand would bring inflation down – the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) had noted in its March 2020 statement that COVID would weaken aggregate demand and ease core inflation.

The nature of the disruption caused by COVID was a key discussion point among MPC members in 2020: what would last longer – the demand or supply shock? This year was also when half the membership of the committee changed, with the first batch of external members replaced by the current three.

Before the reins were handed over, former external member Chetan Ghate sounded a rather prescient warning in August 2020: "Inflation has now been above the upper band of 6 percent for a number of months… Future MPCs should not go soft on inflation."

War and failureOf course, Ghate and the others could not have predicted a war would break out.

The imposition of new restrictions following the second COVID wave pushed inflation past 6 percent in mid-2021, but it cooled down and averaged 5.1 percent that year. However, it was an uneasy truce.

Also Read: One year of Russia-Ukraine war – The economic impact in five chartsBy January 2022, it had edged past the upper-limit of the tolerance band again, with Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 sparking another sharp price rise that forced the RBI to finally admit its failure to meet its inflation mandate.

Critics of the RBI would argue the central bank had failed its mandate in 2020 itself when it said the lack of sufficient price data meant the 'imputed' inflation numbers for April and May constituted a break in the CPI series. But there was no technicality in 2022 when average retail inflation was outside the 2-6 percent range for three consecutive quarters – a report had to be submitted to the Centre detailing the reasons for failure, the remedial actions the RBI proposed to take, and an estimate of the time period within which inflation would return to 4 percent on a durable basis.

Long road to 4%While the first two of the three aforementioned questions can be answered by most central bank watchers – COVID, war, and 250 basis points of repo rate hikes – the third was really up to the RBI. And, going by the RBI's public statements, two years is an appropriate time to bring inflation down to 4 percent. Considering the RBI submitted its failure 'letter' to the government in late 2022, it suggests the central bank would like inflation to be at target by the end of 2024.

Also Read: MPC's Ashima Goyal sees policy pivot if inflation approaches 4% sustainablyThe RBI expects inflation to average 4.3 percent in January-March 2025, but it be lower in the preceding quarters – particularly in July-September 2024. According to Kaushik Das, Deutsche Bank's chief India economist, CPI inflation could fall to as low as 2.7-2.8 percent in July 2024 and average 3.7 percent in the third quarter of 2024 thanks to a favourable base effect. This is broadly in line with the RBI's own forecast of 4.5 percent inflation in 2024-25 in a range of 3.8-5.2 percent.

Inflation may not need a sixth year to return to 4 percent. But more than four years is a long time. And who knows what shocks could come next.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.