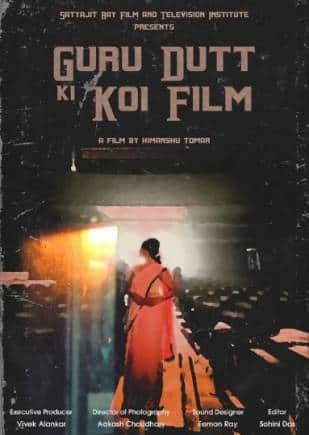

A cinema projectionist who’s been awaiting the return of his now-film-star-wife, who was once the light of his life, is unable to recall her face when she arrives, and resumes writing happy-ending stories. When Himanshu Tomar, 29, was making his graduation film at Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (SRFTI), Guru Dutt and Tennessee Williams came to his rescue. He adapted Williams’ short story Something by Tolstoi (1931) into his short film, Guru Dutt Ki Koi Film (2022). The short story is “thematically similar to Guru Dutt’s personal life,” he says, it aroused in him the same feelings he had when he saw the Arif Zakaria and Sonali Kulkarni play Rahenge Sadaa Gardish Mein Taare in Delhi in 2017, based on the tempestuous personal life of the maverick director and his star-singer-wife, Guru and Geeta Dutt (née Roy). Dismissing Dutt’s films as tragic and sad, Tomar had been scared of watching them until he joined SRFTI.

Poster of Himanshu Tomar's 'Guru Dutt Ki Koi Film'.

Poster of Himanshu Tomar's 'Guru Dutt Ki Koi Film'.

Gurudutt Padukone’s personal life piqued biographer Yasser Usman’s curiosity, leading him to Dutt’s younger sister and now-late artist Lalitha Lajmi (seen in Taare Zameen Par, 2007). “That rare thing of commercially successful films that engage you intellectually, too — that was Guru Dutt’s cinema. It fascinated me to no end. I was particularly intrigued by how personal his cinema actually was. Storylines, scenes and songs, everything reflected his personal turmoil,” says London-based Usman, author of Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story (2020).

Guru Dutt, an introvert in real and reel (Pyaasa’s Vijay; Kagaz Ke Phool’s Suresh Sinha), was that eternal Romantic — lost in his creation. Director Raj Khosla, Dutt’s once-assistant (Baazi, Jaal, Baaz, Aar-Paar) recalled in Nasreen Munni Kabir’s documentary In Search of Guru Dutt (1989), “It is one thing to love and another to say I love you. Guru Dutt loved but could never express it. That was his enigma. The whole thing came out in his films. You couldn’t read through him but I read one thing, he was really lost: Lost in filmmaking, lost to life.”

Guru Dutt's first lead actress Geeta Bali (left) with his singer-wife Geeta Dutt. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

Guru Dutt's first lead actress Geeta Bali (left) with his singer-wife Geeta Dutt. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

“Lalitha Lajmi made the narrative personal and special. So much so that the story of one of the greatest filmmakers of the world became a cautionary tale about mental health. This is where my book is different from all previous books on Guru Dutt,” says Usman. Lajmi shared how Pyaasa’s story was based on their father Shivashankar Padukone, whose clerk job left him and his poetic pursuits frustrated. She narrated a haunting dream about Dutt, who attempted suicide multiple times (each time he was making his classics: Pyaasa, Kagaz Ke Phool and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam) before succumbing to it in 1964. She also speaks of Dutt’s psychiatrist, who’d charge Rs 500 per visit for “just talking” and was never called back.

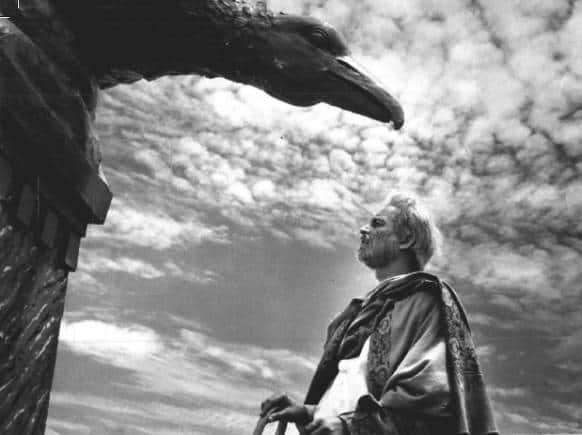

“When the will to destroy the self expresses itself not through the actual act of self-destruction but through a work of art — which is haunted by the visions of self-destruction — it is lifted out of the ambit of personal life,” writes Arun Khopkar, in his pioneering study, ‘Guru Dutt: A Tragedy in Three Acts’ (1985), translated from Marathi by Shanta Gokhale, further mentioning Émile Durkheim’s Le Suicide (1897) and GM Muktibodh’s Satah Se Uthata Aadmi (adapted by Mani Kaul in 1980). In Pyaasa, originally titled Kashmakash, the beetle crushed underfoot and Vijay’s crucifixion of Christ-like pose at the memorial function held at the theatre to mark his supposed death anniversary symbolise the Rousseau-esque relationship of man (artist) at odds with society.

Khopkar writes, “After the long shot of man in Classical literature came the close-up of Romanticism and, with it, came self-expression and confession…the ‘Autobiography’… The most important Romantic work in cinema is found in the work of neorealists of the post-Second World War period… Two outstanding Indian filmmakers in whose work the confessional element plays a vital part are Ritwik Ghatak and Guru Dutt.” Both Ghatak and Dutt deployed the much-scorned “melodrama” and “the melodic aspect of melodrama [as] an essential part of their work”.

The tragic fall of Pyaasa’s poet is symptomatic of the collapse of the euphoria of an ideal modern republic and disillusionment with Nehruvian socialism in newly independent India. While Pyaasa will remain a reference point for films that follow, on the withering and reification of an artist, like Imtiaz Ali’s Rockstar (2011), Oscar Wilde said “all comparisons are odious”.

The iconic Crucifixion of Christ-like pose of Guru Dutt from 'Pyaasa' (1957). (Image via X)

The iconic Crucifixion of Christ-like pose of Guru Dutt from 'Pyaasa' (1957). (Image via X)

Vinay Shukla who directed Godmother (1999) says, “When you look back, the themes he [Dutt] picked up in his films don’t age. A film like Pyaasa and its outrage against capitalism, that an artist has to continuously struggle as commercial consideration tries to suppress that voice, will remain relevant always. Here was a man showing how a story can be told through cinema, who bared his soul historically in his films. In Guru Dutt’s films, external behaviour of the characters didn’t matter as much as their inner turmoil. The hallmark of his narration was his intensity and that of his style was simplicity and minimalism.”

Shabana Azmi in Vinay Shukla's 'Godmother' (1999).

Shabana Azmi in Vinay Shukla's 'Godmother' (1999).

Shukla was inspired by Dutt-VK Murthy’s lighting and tried to play with light and shadow on Shabana Azmi in Godmother. “The round trolley shot in the song Raja ki Kahani in my film was his [Dutt’s] influence on me. I’ve not been imitative of his style but the way he approached things,” he adds.

The use of light and shadow on the caged Meena Kumari in 'Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam' (1962). (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

The use of light and shadow on the caged Meena Kumari in 'Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam' (1962). (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

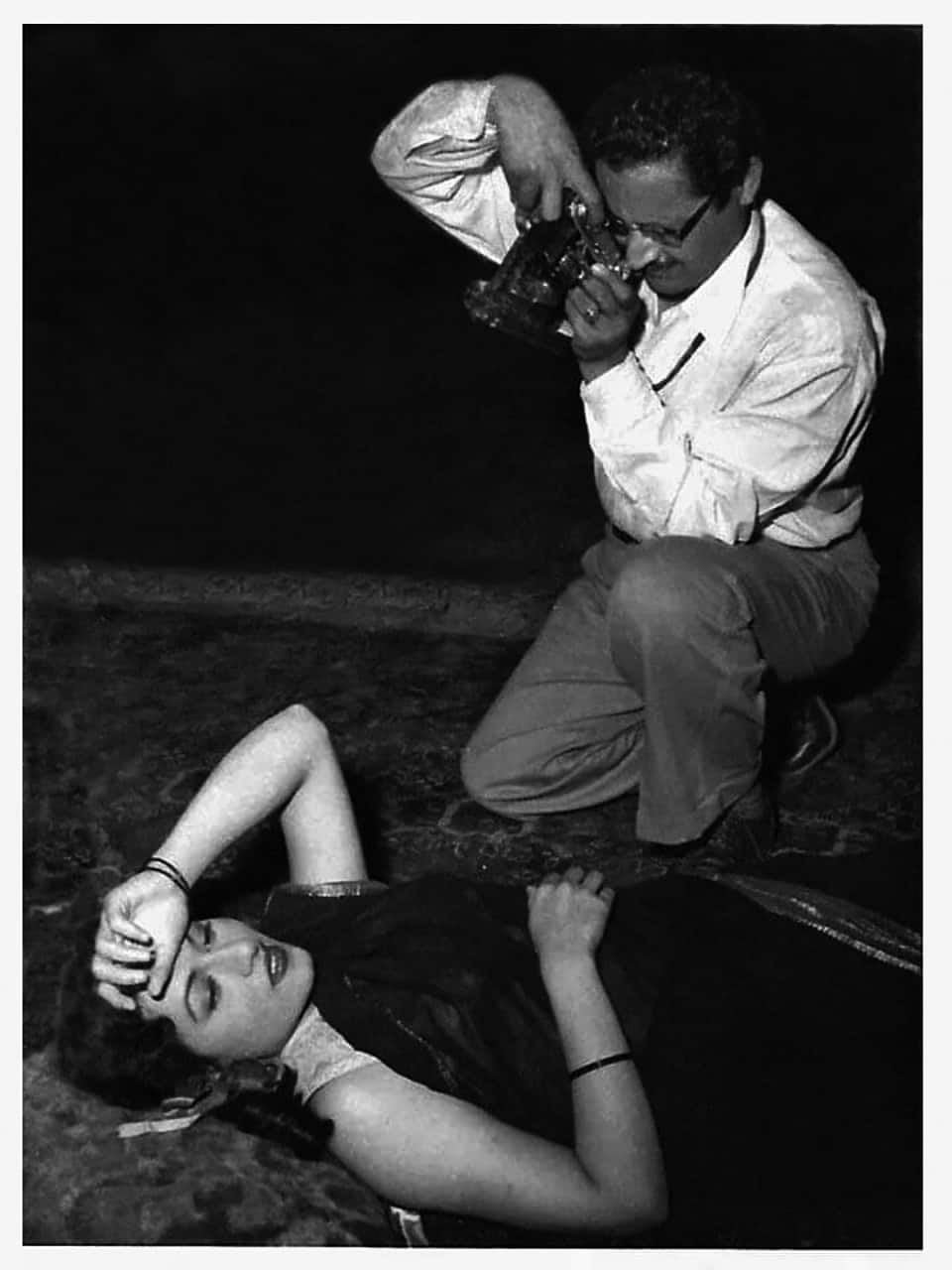

“Lighting played a very important role to convey the state of mind. VK Murthy was a great cameraman, he was really Guru Dutt’s eyes,” says cinematographer Baba Azmi (Mr. India, Tezaab). In his many accounts, Govind Nihalani (Ankur, Manthan) has narrated what his mentor VK Murthy told him the day Guru Dutt died in 1964: “I cried, but more for myself than for him [Dutt].” Murthy and Dutt were a dream team, like Spielberg and Kaminski, David Lean and Freddie Young, aligned in their vision, together they created magic: the round trolley shots in songs, the half-lit face, characters in dark silhouettes, oblong chiaroscuros, the Christ-like shots in Pyaasa, the “mirror shot” in Waqt ne kiya song from his swansong as an official director, Kaagaz ke Phool, India’s first film made on CinemaScope.

![]() An iconic shot from Kaagaz ke Phool (1959) framed inside Mehboob Studios in Bombay. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

An iconic shot from Kaagaz ke Phool (1959) framed inside Mehboob Studios in Bombay. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

“How not to light and how to create shadows, that’s what I learnt from Guru Dutt’s cinema. Today, you see everything through the monitor, if [a shot] is dark, it’s brightened up by adding a light but no thoughts are given prior to shot design,” says Azmi.

In his short life (he died at 39) and an even shorter career (officially directing eight films in 10 years), Dutt dabbled in myriad genres: neo-noir, adventure film, romcom, social drama, says Yasir Abbasi, author of Yeh Un Dinoñ Ki Baat Hai: Urdu Memoirs of Cinema Legends (2018), and “[Dutt] didn’t believe in zooms, he used track and trolley”. In the song Sun sun sun sun zaalima from Aar-Paar (1953), recalls actress Shyama in Kabir’s definitive biography Guru Dutt: A Life in Cinema (1996), “he got the camera whirling around us. There was nothing on that set, just a car in a garage.”

Guru Dutt, Shakila and Johnny Walker in a poster of 'Aar-Paar' (1954). (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

Guru Dutt, Shakila and Johnny Walker in a poster of 'Aar-Paar' (1954). (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

Murthy’s camera would often become a tool to project the character’s emotion, if in Aaj sajan mohe ang laga lo (Pyaasa) song, it moves away from Waheeda’s streetwalker Gulabo and rushes towards Dutt’s poet Vijay, establishing her desire to embrace him but physically/socially she’s unable to; in Kaagaz ke Phool, like the Garuda Eagle statue/symbol of the Ajanta Studios, the camera crane is predatory, it swoops down at a startled Shanti as she walks into the studio. Dutt, who’d trained at Uday Shankar’s dance academy and choreographed for Lakharani (1945), made the camera dance in his own films.

A great shot by VK Murthy in 'Kaagaz Ke Phool' (1959), inside Vauhini Studious, Madras. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

A great shot by VK Murthy in 'Kaagaz Ke Phool' (1959), inside Vauhini Studious, Madras. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

Dutt was a master of filming song sequences, which were plot devices for propelling the narrative forward. Usman says, “[Dutt’s former assistant] Raj Khosla took various creative elements, including the outstanding song picturisation [to his own films]. Indirectly, I felt even Sanjay Leela Bhansali was inspired by him in his earlier films and the fact that he also balances the artistic and commercial elements pretty well.”

Shukla adds, “You can see glimpses [of Dutt’s style] in thriller-maker Vijay Anand films (in the song picturisation in Guide, 1965; the round trolley shot in the song Tumne mujhe dekha in Teesri Manzil, 1966). Manoj Kumar could have been inspired from Mala Sinha’s character in Pyaasa and cast Zeenat Aman as a similar, materialistic character in his 1974 film Roti, Kapada aur Makaan. In a Rishi Kapoor-Tina Munim song from [Subhash Ghai’s] Karz (1980), the lovers’ souls merging is a tribute to Waheeda and Dutt from the mirror-reflection shot in Waqt ne kiya song (Kagaz Ke Phool).”

Azmi narrates how Waqt ne kiya got written, as told to him by his poet-lyricist-writer-father Kaifi Azmi: “SD Burman had created a tune and Guru Dutt told my father: ‘gaana likhna hai’. The situation for the song wasn’t in the script. Kaifi Saab wrote mukhda after mukhda but Dutt was not happy, he couldn’t explain well to Kaifi Saab what exactly he was looking for. So Dutt said ‘drop the song, Kaifi. Come along with me to Poona, to Prabhat Studios.’ They stayed there for a week but the two had stopped talking to each other. While returning in Dutt’s car, each looked out of his window, to the other side. Kaifi Saab uttered then: Waqt ne kiya, kya haseen sitam, tum rahe na tum, hum rahe na hum. Guru Dutt turned towards my father, in a half-smile, and said: That’s it, this is what I want. The car was stopped and song was written.”

So iconic is the song that Amitabh Bachchan sang it for Rishi Kapoor in their last outing together, 102 Not Out (2018).

“Every [Dutt] song is a scene in itself”. Even when Guru Dutt ‘gifted’ films to others, to use Kabir’s words, he held the reins of directing the songs in those films. In his most commercially successful film, M Sadiq-directed black-and-white Chaudhvin ka Chand (1960), Dutt shot the songs in colour. In writer-director Abrar Alvi’s Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam, a commentary on the fall of decaying feudalism, adapted from Bimal Mitra’s novel (previously adapted into the Uttam Kumar-starrer 1956 Bengali film), the song “Na jaao saiyyan was staged in a room, in it a woman (the ethereal Meena Kumari’s Chhoti Bahu) is willingly drowning in intoxication, trying to coax and seduce her husband (Rehman’s Chhote Nawab), to stop him from going to the nautch girls,” says Shukla.

Guru Dutt as Bhootnath and Meena Kumari as Chhoti Bahu in 'Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam' (1962). (Photo: SMM Ausaja Archive)

Guru Dutt as Bhootnath and Meena Kumari as Chhoti Bahu in 'Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam' (1962). (Photo: SMM Ausaja Archive)

In Kabir’s documentary, Alvi speaks of Dutt’s emphasis on the colloquial, spoken dialects and mannerisms for different characters as seen in Aar-Paar (hero from Madhya Pradesh, his Parsi acquaintance and Punjabi lover, adding to Bombay’s cosmopolitanism), which ushered in the modern era in the Hindi film industry and changed how Bollywood wrote dialogues for its characters.

Lyricist Majrooh Sultanpuri, in the documentary, relays how “in Sun sun sun zaalima, Dutt changed the original pyaar mujhko tujhse ho gaya to pyaar humko tumse ho gaya, which Sultanpuri pointed out was grammatically wrong but Dutt interjected, “lafz khushk hai, surr dab jate hain (the words are wry, they flatten the notes), and opted for the easygoing humko tumse.” Alvi notes Dutt’s “wordplay” in dialogues with layered meaning, when in Mr and Mrs ’55 (1955), Lalita Pawar’s aunt Sita asks Preetam (Dutt): ‘Are you a communist?’ he replies, ‘Ji nahin, I am a cartoonist!’ Most of the characters Dutt played: Kalu (Aar-Paar), Preetam (Mr and Mrs ’55), Vijay (Pyaasa), Bhootnath (Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam) are unemployed or seeking a job.

Suresh Sinha’s (Kaagaz ke Phool) is a riches-to-rags story, of a director who accidentally meets a woman (Waheeda) and turns her into a star while he falls from grace. Kaagaz ke Phool would have been called a spin-off of A Star Is Born (1954) or What Price Hollywood? (1932) had it not been Dutt’s most autobiographical work.

Waheeda Rehman as Gulabo from 'Pyaasa' (1957). (Photo: SMM Ausaja Archive)

Waheeda Rehman as Gulabo from 'Pyaasa' (1957). (Photo: SMM Ausaja Archive)

From establishing shots to establishing people’s careers, including his friend Badruddin Jamaluddin Kazi whom he renamed Johnny Walker, Dutt has been instrumental in more ways than one.

Not only have Guru Dutt films fired the imagination of, or eked tributes from, future filmmakers, his songs have engendered films, too. Abbasi says, “Tigmanshu Dhulia’s Saheb Biwi Aur Gangster film series franchise [a modern retelling of the relationship between a man, woman and their servant] is a hat-tip to Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam. Anurag Kashyap has said on record that he made Gulaal (2009) based on Dutt’s song from Pyaasa, Sahir Ludhianvi’s yeh mahalon, yeh takhton, yeh taajon ki duniya…yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaaye toh kya hai. Recall Piyush Mishra’s singing in Kashyap’s film, O ri duniya…yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaaye toh kya hai?”

Piyush Mishra in a still from Anurag Kashyap's 'Gulaal' (2009).

Piyush Mishra in a still from Anurag Kashyap's 'Gulaal' (2009).

In Bombay Velvet (2015), too, Kashyap makes Anushka Sharma’s club singer Rosie (Waheeda Rehman’s iconic character from Vijay Anand’s Guide; Waheeda plays a club singer-dancer in her debut CID) sing Dhadam Dhadam, a reimagining of Pyaasa’s Jala do, phoonk daalo yeh duniya song.

Anushka Sharma in a still from Anurag Kashyap's 'Bombay Velvet' (2015).

Anushka Sharma in a still from Anurag Kashyap's 'Bombay Velvet' (2015).

Sharma also sings Geeta Dutt’s Jata kahan hai deewane, the song that the censor board edited out of the Dutt-produced Dev Anand-Waheeda-starrer CID (1956). Filmmakers Kaul, Kabir, Kashyap, Bhavna Talwar, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, each wanted to make a Dutt biopic.

Waheeda Rehman made her Hindi film debut in Dutt-produced 'CID' (1956), starring Dev Anand. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

Waheeda Rehman made her Hindi film debut in Dutt-produced 'CID' (1956), starring Dev Anand. (Photo: From Yasser Usman’s 'Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story')

“What I love the most about [Dutt’s] craft is what I call the ‘joy of pain’. I can see the beauty in being sad. The pain that he shows is almost aspirational. He was an absolutely phenomenal filmmaker to be able to elicit that kind of response. It is something that I have felt while watching films like Sadma (1983), 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981) and Life is Beautiful (1997),” says adman-turned-filmmaker R Balki, who made a full-fledged tribute to Guru Dutt with his Dulquer Salmaan-starrer crime caper Chup: Revenge of An Artist (2022).

A poster of R Balki's 'Chup: Revenge of an Artist' (2022). (Image via X)

A poster of R Balki's 'Chup: Revenge of an Artist' (2022). (Image via X)

It’s replete with conspicuous Easter eggs: a cover of Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaye, the iconic stone-clicking sound of Jane kya tune kahi (Pyaasa) song as a hook for the killer, the song itself punctuating the lead pair’s love story, the paper flowers (kaagaz ke phool) the anti-hero gifts to the heroine, the Christ-pose by the cop Sunny Deol, and the iconic Kaagaz ke Phool shot in an empty studio and the oblong shadow and light projection. A Kaagaz ke Phool-fanboying psychopath anti-hero hacks down critics in the film, which was co-written by film critic Raja Sen, who was on Balki’s hit list.

“I didn’t start out to make a film as a tribute to Guru Dutt but a tribute to artists in general. On the entire dilemma of criticism versus artistry and where do you draw the line. Kaagaz ke Phool is a classic today but was panned in its time, by absolutely insensitive critics,” he says, adding that most film criticism are “way off the mark, blasé and boring. Critics rushing off to comment echoes trade journalists, but trade journalism and film criticism are poles apart. Critics expect artists to be sensitive on the one hand and thick-skinned to their criticism on the other,” says Balki, who has stopped reading reviews of his films since Khalid Mohammad wrote a “scathing, agenda-driven, review” of Cheeni Kum (2007). “I was really broken. Filmmakers should have a copyright on what they create and sue those [critics included] making money off them,” he says.

Guru Dutt and Madhubala during the shoot of Mr and Mrs '55 (1955). (Photo: SMM Ausaja Archive)

Guru Dutt and Madhubala during the shoot of Mr and Mrs '55 (1955). (Photo: SMM Ausaja Archive)

Shukla says, “As a director, what’s crucial to know is what you are aiming at, what do you want to say and how? And how truthfully you say it — that is Guru Dutt’s legacy.” Though he echoes critics of yore, like Baburao Patel, when he calls Kaagaz ke Phool “an inconsistent film, with apparent commercial compromises, such as the Johnny Walker track and the daughter’s track.”

Khopkar finds the yardstick of “realism” a limited one to gauge Dutt’s works. He records Feroze Rangoonwala’s criticism of Dutt in Filmfare in his book and writes, “Guru Dutt was compelled to work within the framework of the industry. He did not possess the freedom of creation that had made [Satyajit Ray’s] Pather Panchali possible. Even in the three [classics], there are ugly patches of broad comedy and other compulsory additions.” “Barring these three films, there is much spice of the commercial-formula variety in Guru Dutt’s work. In fact, the film industry acknowledged Guru Dutt because his films made money.” Khopkar says, his “assessment of Guru Dutt’s importance as one of the masters of world cinema, as a genuine auteur, has been vindicated by the esteem in which he is held today. The Guru Dutt book (in 1985) was the first expression of my belief in the underlying unity of all artforms, of which cinema is one.”

Sathya Saran would agree. The author of Ten Years with Guru Dutt: Abrar Alvi's Journey (2008) has said, Guru Dutt will become even more important to filmmakers who are trying to break away from the formula.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.