In a fascinating turn of science and narrative, small mice have assisted scientists to go back in time. By inserting a human-specific gene into their genetic code, scientists potentially opened up an early chapter in the history of speech. The modifications were minute but profound—translating squeaks into hints at how humans discovered their voice.

A single gene, a new way to squeak

Researchers at Rockefeller University focused on the NOVA1 gene. This gene is crucial for brain development and is found in many animals. But the human version of NOVA1 contains a special difference in its sequence. That tiny change alters the protein it makes—one that affects vocal expression.

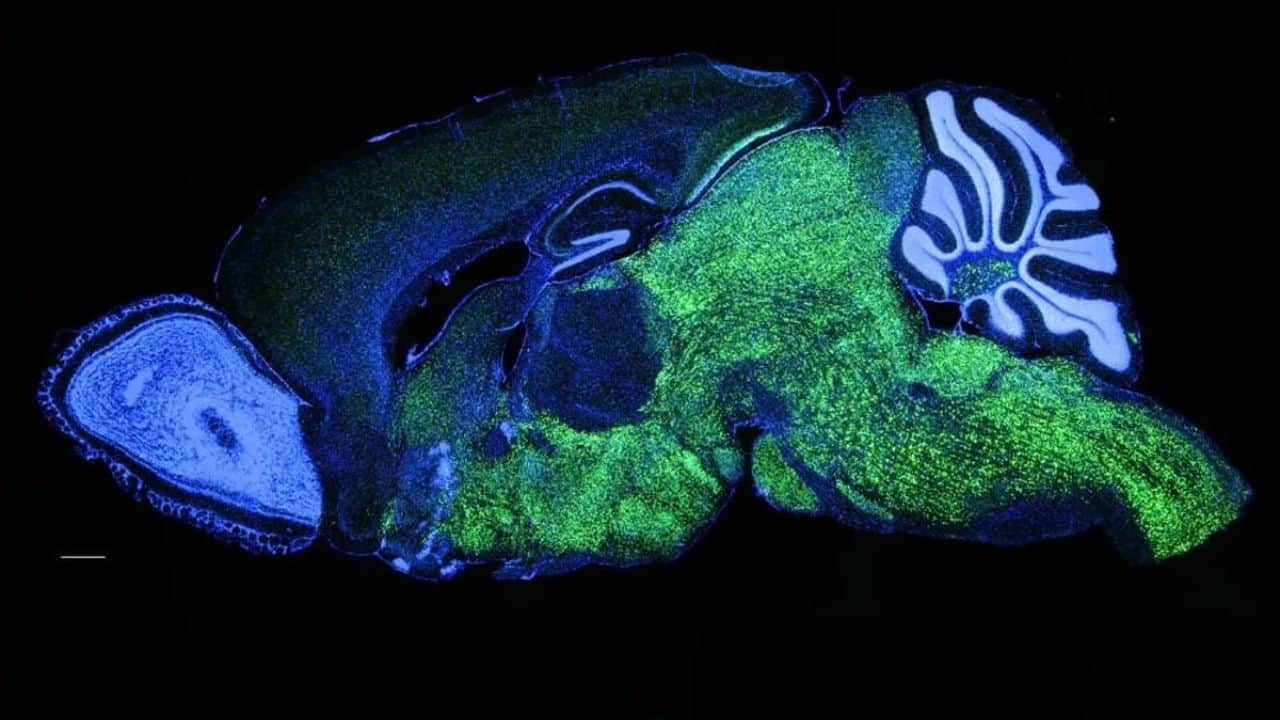

NOVA1 expression pattern in a mouse brain: NOVA1 shown in green, nuclei (DAPI) marked in blue. (Image: Laboratory of Molecular Neuro-oncology at The Rockefeller University)

NOVA1 expression pattern in a mouse brain: NOVA1 shown in green, nuclei (DAPI) marked in blue. (Image: Laboratory of Molecular Neuro-oncology at The Rockefeller University)

To understand the effect of this gene, the team gave baby mice the human version of NOVA1. The results surprised everyone. The modified mice squeaked differently than normal mice. They used higher-pitched calls when calling for their mothers. The range and type of sounds also shifted. These weren’t just soft differences—they were dramatic enough to draw attention to how genetics shape communication.

Rewriting the rules of rodent communication

Normally, baby mice make ultrasonic squeaks to reach their mothers. These sounds can be broken into four sound types—S, D, U and M. After the human NOVA1 gene was added, those squeak letters changed. The new sounds showed that the gene was affecting their ability to vocalise.

As the mice aged, their vocal patterns evolved further. Adult males showed a broader range of high-pitched mating calls. These findings point to a deeper truth: genes don’t just shape brains. They might shape how creatures connect and communicate.

The team noted that the NOVA1 gene plays a key role in the brain. It helps bind RNA and guide movement-related processes. The human version, while similar to the mouse one, uniquely affected vocalisation. Many of the sounds came from genes that are targets of NOVA1. This suggests the gene has a direct hand in shaping how species learn to speak.

A tiny change that humans alone carry

One detail stood out during the study. The NOVA1 version that altered mouse sounds is found only in modern humans. Neanderthals and Denisovans lacked this specific form of the gene. They carried a similar version, but not the one with the I197V amino acid change.

That difference may have played a role in what made us human. Professor Robert Darnell, who led the research, said the result was unexpected. “We thought, wow. We did not expect that,” he said. “It was one of those really surprising moments in science.”

He added that the human version likely appeared in early African populations. It spread far and wide, perhaps enabling humans to develop clearer forms of speech. This small genetic change may have given a crucial advantage. Being able to exchange thoughts and warnings may have assisted Homo sapiens to survive, as other hominins became extinct.

Until recently, the squeaks of some laboratory mice provided a quiet reverberation of our history—one that was shaped by one gene that enabled us to discover our voice.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.