By Julian Novitz, Swinburne University of Technology

“Like most people I read a book or two on holiday,” says Stuart, a character in Julian Barnes’ 1991 novel Talking it Over. He does not have time for recreational reading; it must wait until he is at leisure. His best friend, the erudite but erratically employed Oliver, derides this attitude. To Oliver, a summer reader is a pedestrian one: incurious and intellectually lazy.

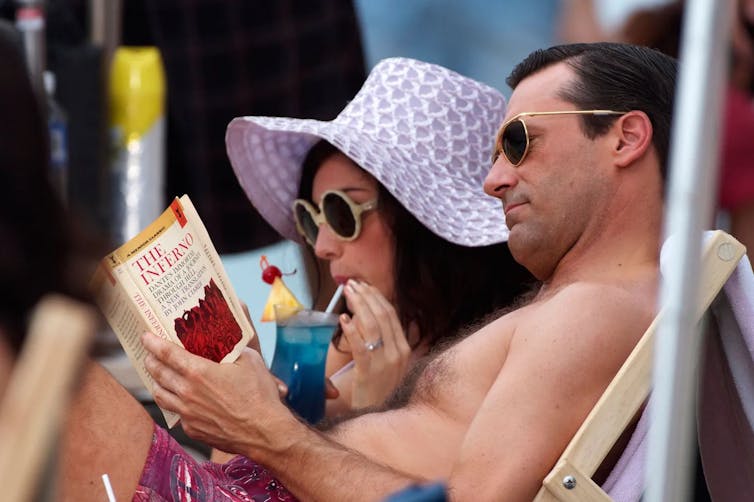

Summer reading – or the beach read – is often associated with undemanding, enjoyable narratives: “middlebrow” literary fiction, thrillers, fantasy novels, historical and contemporary romances. This is even reflected in the physical design of books released in the summer months. Light colours and cheerful covers signal their lack of intimidating seriousness.

While the term “beach read” itself is relatively recent, first appearing in publishing lists and booksellers’ catalogues in the early 1990s, traditions of summer reading are much older.

The anonymous author of the essay Summer Philosophy exhorts vacationers to read books that are “good of their kind”, and offers the volumes of Lord Byron and Charles Lamb’s Ulysses as examples of “perfect” summer reading.

In the United Kingdom, summer months had traditionally been a fallow period for new books. Christmas was the more important holiday period for publishing. But in the post-Civil War United States, publishers and booksellers were becoming aware of the growing appetite for light reading among summer vacationers.

Rising literacy and declining costs of production had made books increasingly accessible, typically in cheap, paper-covered formats. These “dime novels” largely consisted of suspenseful narratives focusing on murder, adventure, and romance. Because of their convenient formats and frequent sales at railway and dockside newsstands, sensationalist, diverting fictions became associated with summer vacation and travel.

By the 1870s, American publishers had begun to capitalise on this trend, launching dedicated summer reading series of “light literature”. These were marketed as a respectable alternative to their dime novel competitors. Summer reads soon became a ubiquitous feature of holiday recreation.

Much like today, summer reading had its detractors. The form of the novel itself was still viewed with suspicion throughout much of the 19th century, and the escapist titles published during the summer season were seen as especially pernicious.

The popular Brooklyn preacher Reverend Thomas De Witt Talmage delivered a memorable denunciation in 1876, labelling summer novels as “literary poison” and “pestiferous trash”, and cautioning his congregants on the shame of being found struck dead with one of those “paper covered romances” in hand.

Others mocked the formulaic conventions and subjects of popular summer titles. The satirical magazine Puck proposed an indexation project (“castles at sunset, pp. 3, 13, heroine’s dresses, pp. 38, 54, 68, 69, 120, 240, 246, 318”), so that readers would be able to skip to their favourite trope.

This list included Frank R. Stockton’s humorous short stories, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s passionate exploration of inequity and exploitation in the Lancashire coal pits (That Lass O’ Lowrie’s), the surreal, proto-science-fiction tales of Fritz James O’Brien, as well as travel writing, histories, and a small collection of Plato’s dialogues.

The Bric-a-Brac series (memoirs and reminiscences of famous writers) was enormously popular in the summer months, as were reprinted editions of international fiction, and holiday collections of classic and contemporary poetry.

Critics and publishers defended summer reading as a necessary “release” from the stresses of the year. But a release doesn’t necessarily imply triviality, and it could clearly be found in many kinds of text.

Lothair was not just a melodramatic potboiler, but also grappled with the challenges of reconciling organised religion with personal faith and morality, which would have resonated with 19th century readers. Popular beach reads may engage with familiar concerns and preoccupations – family, gender roles, history, wealth – in ways that offer a cathartic sense of release and escape.

Like the dime novels and holiday editions of the 19th century, beach reads are often disposable and exchangeable. The remnants of past summer reading seasons can be found in beachside secondhand bookstores, the common rooms of hostels, and on living-room shelves in Airbnbs. Fat, faded books with broken spines, warped and wrinkled from the sand encrusted between their pages.

The best lesson to take from the history of the beach read is that if you can only get through a book or two while on holiday, then make sure they are ones you will like.

This year, a friend of mine will be taking Ulysses with them on vacation, so they can be completely immersed – whereas I’m still looking for a worthy successor to Samantha Shannon’s The Priory of the Orange Tree, which kept me hooked all last summer. Both are perfectly fine beach reads.

As Fran Leibowitz says: “I have no guilty pleasures because pleasure never makes me feel guilty.” This should be our attitude to recreational reading all the time, but the summer beach read provides the best opportunity to fully embrace it.

This year’s summer reading lists – literary, historical, fantasy, thriller, and more – probably contain many novels that are “good of their kind”, regardless of their genre or cover design. And if they’re not, then you might enjoy them anyway.

Everyone needs their own kind of release.![]()

Julian Novitz, Senior Lecturer, Writing, School of Media and Communication, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.