Abhijit Bhalerao’s The Man Who Avenged Bhagat Singh begins with a scene of ritual bloodshed — two young Indian revolutionaries circa 1932, Baikunth Sukul and Chandrama Singh, are on the outskirts of Bettiah, the Bihar town where they have to pull off an assassination. But before they embark on an irreversible course of action, the two give in to superstition and cut themselves with a khukri (a small, curved blade favoured by Gorkha soldiers). As Baikunth says, “To fully realize the strength of the blade, a khukri must taste blood.” And so it is that these two young men shed their own blood by the riverbank.

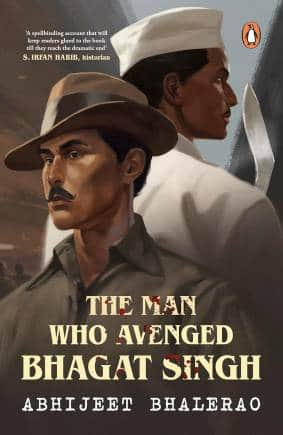

The Man Who Avenged Bhagat Singh

The Man Who Avenged Bhagat Singh

What's interesting about this scene is that neither Baikunth nor Chandrama thinks of themselves as particularly religious or superstitious but by the end of the conversation they have talked each other into the ritual. This scene is almost a metonym for the revolutionary life itself — the line between extreme self-belief and mythology remains as thin as ever. Some small measure of suspension-of-disbelief is required to convince yourself that you’re a revolutionary. How else is one supposed to summon up the unimaginable levels of courage displayed by these twenty-something young men?

The novel is a fictionalized retelling of the assassination of Phanindra Nath Ghosh, the former revolutionary who later turned approver for the British government in India. Ghosh’s testimony was instrumental in the death sentence handed down to Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru. For Ghosh’s betrayal, the HSRA (Hindustan Socialist Republican Association) approved the punishment of execution against him and that’s exactly what Baikunth and Chandrama carried out. The operational details and the interlocking set of circumstances around the assassination itself are depicted in the book’s second half, mostly—the first half shows us the sequence of events that led up to that moment. This gives Bhalerao the chance to introduce us to the full cast of revolutionaries, including Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekhar Azad, Jatin Das and several other individuals who are household names in India now.

Bhalerao’s style is accessible, straightforward and clearly informed by the great spy novels of John Le Carre and others. You want to keep turning the pages to follow the fast-moving plot, but along the way, the novel also keeps making sly, ‘commonplace’ observations about politics, Indian society and colonialism. This way, the readers are entertained but also kept on their toes throughout.

The spy-novel influence can also be seen in the dialogue. Sample this, for example, where Chandrashekhar Azad is advising Bhagat Singh on a revolutionary’s code of conduct—a sort of ‘trust nobody’ cautionary rant that would have worked just as well in an espionage story.

“You are playing a dangerous game. Except for yourself, nothing and no one can be trusted. Your worst nightmare can come true. Your friends and brothers will turn approvers, and they will sabotage everything sacred to you. I have gone through this pain in Kakori. Most of my friends died because of the traitors. What is the guarantee that it won’t happen again? This is the country of Mir Jafar and Jaichand. This is why I prefer to fight as long as I am free.”

There are parts of the novel that use well-known lines spoken or written by these revolutionaries. The diaries of Bhagat Singh are probably a major source. (Indeed, Bhalerao translated Bhagat jail notebooks as Shaheed Bhagat Singh Yanchi Jail Diary in Marathi almost a decade ago.) When Jatin Das, a pacifist bomb-maker, is finally convinced to join the resistance, he tells Bhagat Singh sarcastically, “Tell me, where do I have to die alongside you guys?” (You might remember this moment from The Legend of Bhagat Singh starring Ajay Devgn.) When Phanindra Nath faces Bhagat Singh after becoming an approver, the latter mocks his former colleague by pointing towards the ground and saying, “You’ve betrayed her, not me”. These moments are carefully unfurled by Bhalerao, especially in the book’s second half—the author realizes these are ‘showstopping’ or ‘paisa vasool’ moments, the equivalent of a crowd cheering at a punch line inside the cinema hall.

The Man Who Avenged Bhagat Singh is a great starting point to understand the everyday texture of the revolutionary life, especially for younger readers. It has the velocity and panache we associate with well-written commercial fiction and its historical research is basically faultless. Read it to experience one of the most fascinating phases in Indian history.

The Man Who Avenged Bhagat Singh by Abhijeet Bhalerao (Pages: 376; Price: Rs 350), published by Penguin Random House India.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.