What is it like to live a double life for six decades? Do we have a name for ‘it’—same-sex attraction—until society gives it one: sin? When can one finally decide if it’s a safe time and place for them to come out, and to whom?

Laura Hall in her exquisitely crafted and deeply moving memoir Affliction: Growing Up with a Closeted Gay Dad (She Writes Press, 2021) unearths answers to these questions, treading expertly the personal and political with her measured and taut recollection of her family life in the San Francisco Peninsula.

Because her father used to speak to her “as an equal”, Laura could ask anything and got pointed responses from him. However, whenever she asked him why he changed his name from Duane to Ralph, she got a different response each time.

She had her ‘doubts’, because none of her friends’ fathers used to style their wives or children or were flamboyant as Ralph was, yet she remembers her father to be the “manliest of men”. This is why, in 1975, after 33 years of being married to his wife Irene, when Ralph came out to her 24-year-old daughter—“Honey, I’m gay. I’ve always been gay”—Laura felt as if “the weight of his secret had shifted from his shoulders to mine.”

She was part flummoxed and part annoyed: what should she do of the story, meticulously told with delightful details, of how her parents had met at a dance party? That they decided to marry each other after a short while and made up for years of separation during wartime by having “four babies in five years”? The anger or annoyance subsided only after learning everything about her father in the years to come.

Irene Hall (18), 1942; Ralph Hall (24); 1942 | (Image Courtesy: 'Affliction'; Laura Hall)

Irene Hall (18), 1942; Ralph Hall (24); 1942 | (Image Courtesy: 'Affliction'; Laura Hall)

Laura learns that father was sacked from Crowley Company, despite being a valued partner, because the “US Civil Service Commission found out from a 1940 arrest that he was gay.” By 1975, this law had cost “more than five thousand federal employees” their jobs for being gay and lesbian.

The infamous Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) setup arrests, in which Ralph was convicted, made ‘Duane’ reinvent himself as ‘Ralph’. He was “free of the psychologist and the fees, but not of his record.” (The US courts would make gay people undergo therapy, which they’d have to pay for, as punishment.) Unable to “accept the horrors of being queer” any longer, Duane sanitised his previous life to become Ralph and joined the US Army.

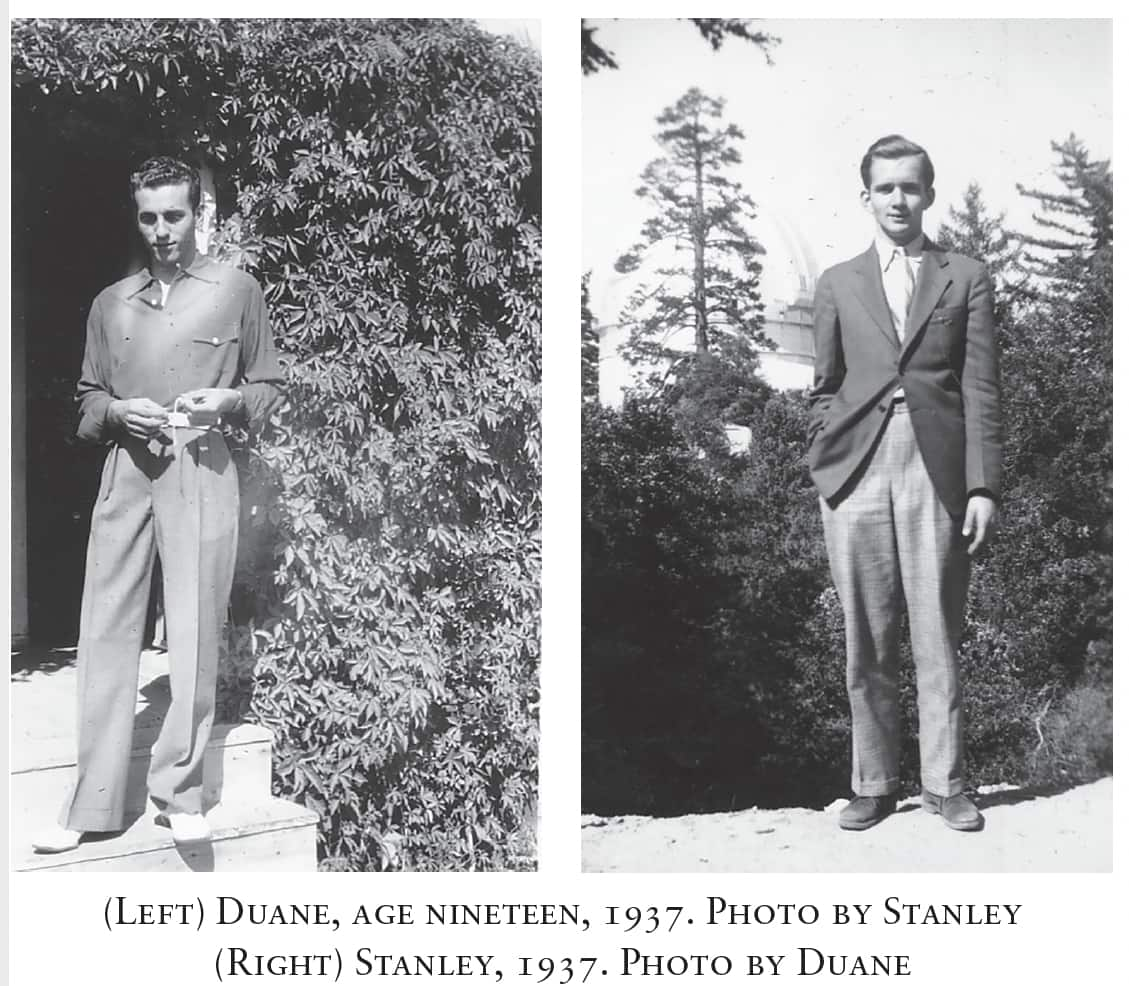

On his deathbed, Ralph, then 90, said he wished he had tried harder to live with Stanley Hughes. (All images from 'Affliction')

On his deathbed, Ralph, then 90, said he wished he had tried harder to live with Stanley Hughes. (All images from 'Affliction')

Unlike other memoirs, Laura’s is not marred by the myopic family-centric narrative, trying to gain sympathy by selling vulnerability, it’s as much a personal story as it’s a historical record of how queer people, through the generations, have been persecuted or stripped of their dignity for being their authentic selves. And in the event of lack of support from the civil society, how they had mobilised support during the AIDS epidemic, which was much popularised as ‘gay cancer’ or how one senator put it: “God’s wrath on homosexuals”. Laura recalls how her father, too, after coming out, started participating in organising such initiatives.

Laura’s prose is also well researched. She has investigated every detail that her father had shared with her. However, candid conversations in this book are equally reflective. One, in particular, is between Laura and her granddaughter Cassie. Laura asks Cassie if she knew her great-grandfather was gay and remained closeted for six decades. Cassie replies: “Yeah, Grandma. He wanted to stay alive.” She put eloquently what Laura could not. Laura finds this change heartening. But, in fact, she was the one who took the first step by educating her daughter Jody about same-sex attraction after her father had come out to her. The initial step is showing effect in the second generation. Laura demonstrates how heterosexuals can be good allies: by propagating that being LGBTQIA+ is a nonissue.

(Image Courtesy: 'Affliction', Laura Hall)

(Image Courtesy: 'Affliction', Laura Hall)

But one can never know what it looked like living in the times when it used to be an issue, a big one at that. Sample this excerpt from a 1943 letter which Ralph wrote to Irene: “There’s that restless, dissatisfied, other self of mine that is continually trying to make itself heard. Though I hate myself for allowing it, occasionally I lose the battle—with the result that I fall far short of the standards that my wife and friends and family have set for me.”

Ralph’s internal conflict is clearly linked to his homosexuality. Irene couldn’t have fathomed it, of course. However, she eventually came to know about it in 1957, when she broke a lock on the box and discovered some photographs. Ralph wanted to leave the family after this incident, but Irene threw her arms around her husband and said, “Please, Ralph. Please don’t leave. I still love you.” Laura always wondered what made her continue with the marriage. She gets an answer to this question, too: Irene wanted her children to have a father because “she never did”.

How devastating it would have been for Irene, no matter how respectful and loving Ralph had been, to surrender her life, knowing she would not get the love that she deserved? However, it must be unbearably suffocating for Ralph, too, who gave his life for the family but knew early on that he was attracted to men, that he was “different”, but “didn’t have a name for it”. He only knew what society wanted him to know: that he “should conceal it, that it was an affliction”. Because of which he stayed in the closet for six decades.

In 2008, at the age of 90, on his deathbed, when asked by his daughter if there’s “one thing you most regret about your life,” Ralph said: “I regret not trying harder to find a way to live a life with that sweet young man, Stanley Hughes.”

Reading this, I was reminded of Bronnie Ware, an Australian nurse, who wrote a book The Top Five Regrets of the Dying: A Life Transformed by the Dearly Departing (Hay House, 2012). Years of being in palliative care, she learnt that the top regret among the dying was: “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

Ralph died with a regret. This, I’m sure, is one of the legacies that Ralph wouldn’t want his future LGBT generations to carry forward.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.