Sylvester Stallone has been in the film business for nearly 50 years. But he has been in the “hope business”—as he calls it in the new Netflix documentary Sly—for a lot longer. It might seem like a strange thing to say about a man who’s best known for turning the craft of pugilism into a multi-million-dollar film business, but hope, or the pursuit of it, has been at the core of Stallone’s enterprise.

For several generations, Stallone, the man behind iconic Hollywood franchises Rocky and Rambo, was the ultimate portrait of masculinity, but he also represented the underdog who prevailed over his circumstances—both in person and the larger-than-life characters he brought alive on screen.

Premiere of Sylvester Stallone's movie F.I.S.T. in April 1978. (Photo by Alan Light via Wikimedia Commons 2.0)

Premiere of Sylvester Stallone's movie F.I.S.T. in April 1978. (Photo by Alan Light via Wikimedia Commons 2.0)

Now nearly 80, Stallone is still throwing punches—a reality show with his children, films like Tulsa King, Expendables 4 and the upcoming Levon’s Trade. As an aspiring actor who also wrote and later directed, Sylvester Stallone casts a long shadow on ’80s Hollywood. What keeps him from being just another has-been—what keeps Sylvester Stallone standing?

Sly offers some insight and fascinating biographical details. Stallone’s story begins in the rough-and-tough New York neighbourhood called Hell’s Kitchen in 1946. Born with a slur due to an accident, raised in a traumatic environment, Stallone was the troubled child who attended 13 schools in 12 years, never really good at academics, more inclined towards jock-like activities.

The desire to act, the film suggests, was born early—perhaps out of a desire to find the right role models, which he did in Steve Reeves as Hercules in the 1958 film by Pietro Francisci. Stallone grew up idolizing this “perfect well-built role model”. After a short-lived stint with playing polo—a potential career that the film suggests didn’t endure due to Stallone’s father—he moved to New York to study acting.

Years of struggle followed—in New York and LA. Even after a notable debut in the 1974 film Lords of Flatbush, Stallone, with his droopy eyes and slur was deemed “uncastable”—or at best, cast as a thug. So he began to write his own scripts, inspired by the testosterone-fuelled cinema of the time, such as Martin Scorcese’s Mean Streets.

The story of how Rocky got made is the stuff of urban legend. Walking out the door after an unsuccessful audition with well-known producers Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff for a different project, Stallone happened to mention that he also wrote a bit. The producer-pair was kind enough to ask him to send them his stuff. Stallone sent across a script that he had already sold to a different set of newbie producers, which they liked but could not work out.

Disappointed but noticing that “the window of opportunity had not closed”, Stallone and his (first) wife got a new script together in just three days—which got greenlit if the budget were kept low enough. Stallone also had to fight to keep his part as the leading man; instinctively knowing that if he sold this as a script, he would lose out on a lot.

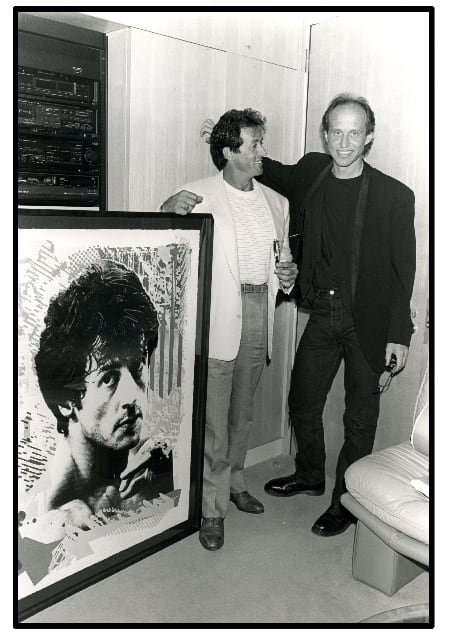

Sylvester Stallone with Jim Evans. (Photo credit: Robert Knight, Jim Evans via Wikimedia Commons 4.0)

Sylvester Stallone with Jim Evans. (Photo credit: Robert Knight, Jim Evans via Wikimedia Commons 4.0)

In 1976, when Rocky first hit theatres in the US, it became that rare word-of-mouth monster hit that went on to take an Oscar. It signalled the arrival of a new superstar and even a new genre. Stallone had reinvented the “likeable thug” character—the sensitive lugnut who was more man than machine.

Stallone is also believed to have re-invented the action movie genre, which took centre stage in the 1980s, a time that also erected poster boys in Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis and Jason Statham. In his own words: The action movie before Rocky was simply made up of car chase sequences, but in this period, it came to rely more heavily on the physicality of the lead character.

In Stallone’s case, at least, it wasn’t just the physicality—these were, in retrospect, movies with a lot of heart, and for their time, deeper investigations of masculinity than had been seen in commercial cinema. Through its many chapters, Rocky was never simply a boxing movie—it was also a love story, a family drama, a treatise on parenting. They were all also deeply personal: Stallone drew deeply from his own experiences in real life, often even reconciling with his flaws, absences and mistakes through Rocky Balboa.

Rambo, Stallone’s other big franchise, still astounds with its acute portrayal of PTSD, embodied in a war veteran who’s lost everything, including his own humanity. The successes of Rocky and Rambo, hall-of-fame Hollywood franchises, were built on Stallone’s deep need to “save people”, the observation that people do not like to watch their heroes dying on screen (even if that’s what happened in real life) and a preternatural belief in the personal redemption story.

All of this, Stallone combined with a business acuity that told him to never “discount the sequel”. It’s this very formula that helped him gain third wind in the 2010s, with the Expendables series—bringing the biggest action stars of yesteryears onto the same playing field, that was as much a meta joke as it was a genius move.

Actor Sylvester Stallone on the Expendables panel at the 2010 San Diego Comic Con in San Diego, California. (Photo by Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons 2.0)

Actor Sylvester Stallone on the Expendables panel at the 2010 San Diego Comic Con in San Diego, California. (Photo by Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons 2.0)

Stallone’s story is a remarkable one, and the talking heads on Sly, directed by Thom Zimny—including Quentin Tarantino and Henry Winkler—provide immense insight into his value and influence upon Hollywood, not just a certain era, but stretching well into the 21st century.

At a time when celebrity bio-documentaries are a dime-a-dozen—each masquerading as its own kind of inspirational story of the triumph of human spirit—Sly’s value is in expertly documenting a pre-Internet slice of time, perhaps the last decade that such raw masculinity held such sway over the imagination of the masses.

It’s no small coincidence that we are reckoning with Stallone’s version of virility in the same year that we’ve seen it decimated at the hands of current Hollywood’s biggest filmmaker. Greta Gerwig’s portrayal of Ken in Barbie, she has said, relied heavily on Stallone (and Rocky and Rambo’s) maximalist persona, which, at least in Sly, is given a softer sheen.

As critics have noted, there is much that Zimny does not touch upon in Sly—the allegations of abuse against Stallone; no mention of Creed, the Rocky spinoff that actually earned Stallone his last Oscar nomination; his own families and relationships (he’s been married thrice) talked of in abstract, his late son Sage’s death but a footnote; his tangle with body enhancement drugs completely eclipsed. Sly is, no doubt, a moving, inspirational take on a giant of English-language cinema—but it also comes across as somewhat smitten with its subject, and myopic in its view of the man’s cultural impact.

Still, Sly does a good job of defining Sylvester Stallone’s key persuasions—and hope, it is clear, is central to both his personality and his fortune. That spirit of “hope” is perhaps best encapsulated in what is now famously known as the “Rocky Steps” scene.

Towards the end of Rocky, which is a story about a down-and-out thug with no prospects, who finds purpose in life as a fighter, Stallone runs through the city of Philadelphia, as the iconic soundtrack plays in the background. At this point Rocky Balboa has lost a critical match to Apollo Creed, but in this morning training session, he embodies the triumph of self—skipping up the 72 steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and raising his arms up to sky in a gesture of victory.

The Rocky Steps scene is film canon—the kind that film students pick apart to understand why cinema is magic, and the kind that generations after hark back to. Will Smith (The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air), Eddie Murphy (The Nutty Professor), Toni Collette (In Her Shoes), Lisa Simpson (The Simpsons), have all retraced Balboa’s steps, and helped build a cultural cornerstone out of this one scene in this iconic film that, as a critic in Sly says laughingly, “is rigged to make you feel like Rocky won.”

Netflix’s Sly does much the same thing. As Stallone sits in his LA mansion, packers around him wrap up his house because he now wants to move East. He wants new adventures, his priorities have shifted. He listens to old cassette tape recordings of himself, and reacts to older versions of himself. He is candid, astute, thoughtful, considerate. He is, oddly, presented as a “poet, philosopher, artist”—three words no one has ever associated with Stallone. When he talks about hope, you know that Sly is rigged to make you feel like Stallone has won.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.