What is left to be said about Raja Ravi Varma, the princely artist from Kerala who gave the nation an everlasting visual imagery of gods and goddesses? Since there is no dearth of scholarly books and articles that focus on the life and work of the artist, this was what even lawyer Ganesh Shivaswamy wondered when the idea of writing a book on the artist was suggested.

The Bengaluru-based lawyer and an avid collector of Raja Ravi Varma’s chromolithographs has been interested in the works of Raja Ravi Varma and even founded the Ganesh Shivaswamy Foundation which, focuses on structuring the legacy of the artist. But when he toyed with the idea in 2018, it was to write on the legacy of the Ravi Varma Press. On a visit to Kilimanoor Palace, the serendipitous find of a wooden box, unattended for decades, containing the reference materials relied on by the artist, set Shivaswamy on a new narrative.

The cover of the first book of a six-volume series called 'Raja Ravi Varma: An Everlasting Imprint'.

The cover of the first book of a six-volume series called 'Raja Ravi Varma: An Everlasting Imprint'.

Today, he is set to launch the first book of a six-volume series called Raja Ravi Varma: An Everlasting Imprint, which has delved into information gathered from images from museum displays and store rooms, governmental, institutional, and personal archives, from personal collections and conversations with a range of people. “My work begins when Ravi Varma’s images got into the common man’s life,” Shivaswamy says, “It delves into the trajectory of the images, the people behind the scenes, the models featured in the paintings, and the artist’s legacy in the social narrative.”

Here are some images and their impact which have been featured in the series, as told by Ganesh Shivaswamy:

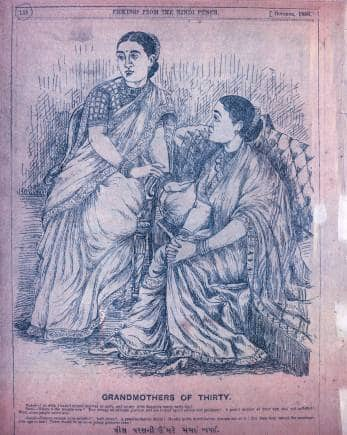

A powerful illustration that changed the law

The illustration 'Grandmothers of Thirty', a powerful illustration that changed the law, showed two ladies called Gunga and Seeta, wearing shoes and seated in the poses of Radha and her sakhi as they converse. This inspired Raja Ravi Varma to paint

The illustration 'Grandmothers of Thirty', a powerful illustration that changed the law, showed two ladies called Gunga and Seeta, wearing shoes and seated in the poses of Radha and her sakhi as they converse. This inspired Raja Ravi Varma to paint

A year after the Radha chromolithograph was published, it inspired a cartoon in the satirical magazine, Hindi Punch, titled Grandmothers of Thirty. The illustration showed two ladies called Gunga and Seeta, wearing shoes and seated in the poses of Radha and her sakhi as they converse:

The illustration 'Grandmothers of Thirty', a powerful illustration that changed the law, and inspired Raja Ravi Varma to paint this (pictured), showed two conversing ladies Gunga and Seeta

The illustration 'Grandmothers of Thirty', a powerful illustration that changed the law, and inspired Raja Ravi Varma to paint this (pictured), showed two conversing ladies Gunga and Seeta

Gunga: I do wish I hadn’t myself married so early, and let my little daughter marry early too!

Seeta: Where is the trouble now? You occupy an enviable position and are looked up for advice and guidance! A grand-mother at your age and not satisfied? Well, some people never are!

Gunga: Reason enough to be satisfied! Isn’t there? A grand-mother at thirty! Hardly in the world before you are out of it! It’s time they raised the marriageable age in law! There would be no more young grannies then! The minimum marriageable age was the subject matter of the first legislation in India when the Age of Consent Act was passed in 1891. This fixed the minimum age for consensual sex at 12 years but did not address the minimum age for marriage. Hence, when the illustration appeared in the Hindi Punch, this was still a burning issue. The grievance espoused by the ‘Grandmothers at Thirty, cartoon was finally remedied only by the Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, which fixed the minimum age of marriage for boys at 18 and girls at 14. In more recent times, this age has been revised to 21 and 18 through the promulgation of the Child Marriage Act of 2006.

Background: At the time when this illustration was published, British India was steeped in controversy and litigation battles related to a woman’s right to refuse to cohabit with her husband. This came to the fore when Rukhmabai of Bombay to this issue to the High Court of Bombay. Rukhma was married at the tender age of 11 to Dadaji Bhikaji in 1876 and when she turned 19, she refused to go to the house of her husband. This led to the filing of a petition, seeking a restitution of conjugal rights by the husband, which came up before Justice Robert Hill Phinney in 1884. Phinney opined that since Rukhma was still a child at the time of her marriage, her consent was contractually invalid. This judgment was however soon reversed, leading to Rukhma writing in the press and even petitioning Queen Victoria. The queen eventually intervened and annulled the marriage. Rukhma went on to train as a doctor in London and returned to practice in Gujarat.

A painting that became popular iconography

The painting first became a chromolithograph and then propelled into the public space which, later, artists then made it their own, the representation showcased here is by artist S Murugakani.

![]() From (left to right) a painting to Raja Ravi Varma's chromolithograph, to a popular iconography in an artist's recreation by S Murugakani.

From (left to right) a painting to Raja Ravi Varma's chromolithograph, to a popular iconography in an artist's recreation by S Murugakani.

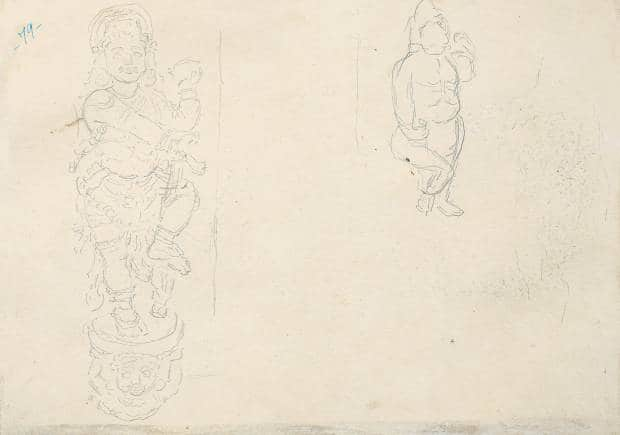

A hitherto unseen drawing of Raja Ravi Varma

One of the artist's greatest talents was his ability to diligently document many aspects of life, be it textiles, draping styles, adornment, sculptures, and so on. Here is an example of a sketch and the actual dwarapalaka.

A dwarapalaka statue that inspired a hitherto unseen drawing of Raja Ravi Varma's.

A dwarapalaka statue that inspired a hitherto unseen drawing of Raja Ravi Varma's.

A hitherto unseen drawing of a dwarapalaka by Raja Ravi Varma.

A hitherto unseen drawing of a dwarapalaka by Raja Ravi Varma.

An inspiration found in the wooden box

This painting of the Reclining Nair Lady have been said to be reminiscent of Edouard Manet's painting, Olympia. “That was simply not true,” Shivaswamy said. The inspiration was from an illustration found in one of the many art journals which Ravi Varma owned.

A painting from an art journal that inspired Raja Ravi Varma to paint the 'Reclining Nair Lady'.

A painting from an art journal that inspired Raja Ravi Varma to paint the 'Reclining Nair Lady'.

Raja Ravi Varma's painting, 'Reclining Nair Lady'.

Raja Ravi Varma's painting, 'Reclining Nair Lady'.

Using photographs as study

Rajibai Mulgaonkar was photographed at Ravi Varma’s studio where she struck several poses in front of a background. These photographs were used by Ravi Varma (for painting Lakshmi and Ahalya) as well as his brother C Raja Raja Varma who was also an artist and painted in the studio. This photograph is Raja Raja Varma's painting.

Rajibai Mulgaonkar was photographed at Ravi Varma’s studio where she struck several poses, these photographs were used by Ravi Varma for painting Lakshmi and Ahalya.

Rajibai Mulgaonkar was photographed at Ravi Varma’s studio where she struck several poses, these photographs were used by Ravi Varma for painting Lakshmi and Ahalya.

Ravi Varma's painting Lakshmi and Ahalya was inspired from the photographs of Rajibai Mulgaonkar clicked at Ravi Varma’s studio.

Ravi Varma's painting Lakshmi and Ahalya was inspired from the photographs of Rajibai Mulgaonkar clicked at Ravi Varma’s studio.

Horse

Did you know Raja Ravi Varma painted and sketched horses very well? This was probably because the vahan of his family deity, Sastha (Shaastha), was a horse, the seal of the Kilimanoor family is also a horse and the logo of this book series is also fashioned from a horse. It is an animal associated with energy and power. This rare watercolour sketch of a horse by the artist features in the first volume of the series.

Raja Ravi Varma's 'Horse'.

Raja Ravi Varma's 'Horse'.

Societal influences

In the 1890s, around the time the Malayali Lady was painted by Ravi Varma, the women from Kerala dressed differently to indicate their caste and position in the society. In Travancore, tensions brewed as only the Princesses and Zamorin (women from royal household) could cover their breasts while the rest could cover themselves unless in the presence of upper caste women. It was called the upper garment dispute or the breast tax. Later, according to Shivaswamy, the Zeenat Aman-starrer film Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978) revisited the painting by draping the protagonist in a manner similar to the Malayali Lady painting. “It is documented that JP Singhal, the photographer, was inspired by Raja Ravi Varma,” he says. “Talk about the influences of Ravi Varma’s iconic artworks.”

Raja Ravi Varma drawing inspiration from society, from how the women of Kerala dressed differently to indicate their caste and position in the society.

Raja Ravi Varma drawing inspiration from society, from how the women of Kerala dressed differently to indicate their caste and position in the society.

Depiction of Ravana

One of the mentions in a suit (now dismissed) against Adipurush film about its alleged unflattering depictions of Lord Rama and Ravana was Raja Ravi Varma’s depiction of the Ramayana in a positive light. Ravi Varma painted Ravana just thrice: Jatayu Vadha (1906), Ravan and Sita (1910), and Victory of Indrajit (circa 1910). “He painted Ravana as a muscular, dark-skinned man which was the way he visualized the demon king.”

Raja Ravi Varma's depiction of Ravana in his famous painting 'Jatayu Vadha' (1906).

Raja Ravi Varma's depiction of Ravana in his famous painting 'Jatayu Vadha' (1906).

Raja Ravi Varma hailed from the aristocratic Kilimanoor family of the princely state of Travancore. His artistic talent was recognised and patronised by the Maharaja of Travancore. He trained in water colours by Rama Swami Naidu and oil painting by British portraitist Theodore Jenson. In 1881, the newly crowned maharaja of Baroda, Sayaji Rao Gaekwad III, invited Ravi Varma to make his portrait. Thus began a series of commissions from the Maharaja resulting in iconic paintings like Shakuntala, and more. Ravi Varma travelled the length of the country — from Travancore to Lahore — sketching whatever he saw. At an exhibition of his works in Mumbai in 1894, the artist was stunned by the lines of people queueing up to see his paintings. He decided to set up his own press to reproduce affordable lithographs of his paintings. The press was financially unsuccessful, plunging Ravi Varma into debt. Towards the end, he sold the press to Fritz Schleicher, a German lithographer, who used the mythological figures on products like match boxes, fliers, advertisements and calendars. The calendars were a huge hit and changed the visual imagery of gods and goddesses.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.