The government has launched a massive repatriation effort to bring back thousands of Indians stranded across the world following the coronavirus outbreak. Students, from neighbouring Bangladesh and as far as the United States, are among those headed home as part of the Vande Bharat effort.

The repatriation of students is a stark reminder of the failure of policymakers to build educational institutions of eminence. This is best illustrated by the number of students going overseas for higher studies.

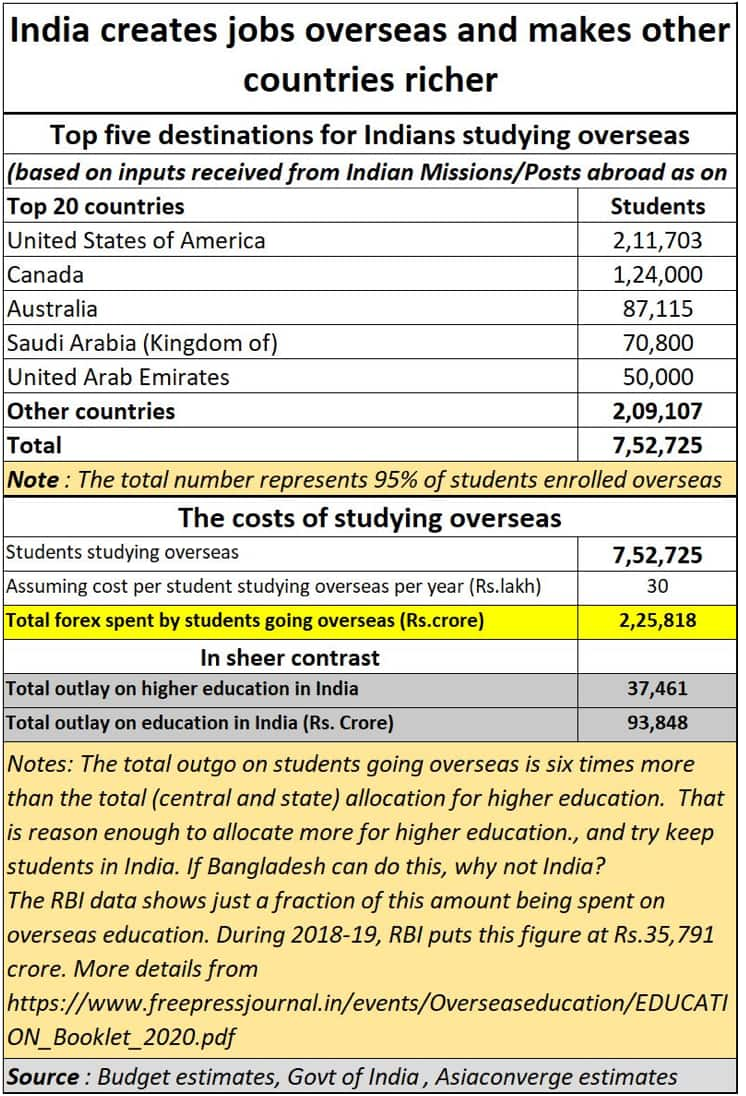

An exact number is difficult to arrive at but by adding the figures reported by overseas Indian missions, it is possible to reach a fair number. These numbers are likely to be higher, as they don’t include students who go for a vacation, stay with relatives or friends and enrol for short-term specialised courses in lesser known institutes.

Even an approximation of the numbers is important.

It gives information about the countries Indian students prefer. A time series can tell us about popular countries and those that have fallen out of favour.

For instance, the UK saw a drop for two years running until it allowed students to work for two years after graduation.

But the UK, as well as the US, can be expensive. Canada appears to have the most interesting possibilities for students who want to work overseas.

In the UK, which accounted for a total of 16,550 students as in July 2018, a student on an average ends up paying around $114,000 (around Rs 80 lakh annually.

The US is more expensive at $140,000 (Rs 1 crore) at well-known universities. Canada is a tad cheaper than the UK but it is the EU and China that are more economical.

Most EU member-countries offer full scholarships to foreign students. Selection is tough and merit-based.

Many countries do not charge tuition fees and students only have to bear living and entertainment expenses. Experts put the average annual expenditure for such students at around $15,000.

But there are only a handful of Indians at EU universities—that is why they are bracketed as “Other Countries” in the table alongside.

In 2018, Germany had 15,308 students from India, most of them for STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) courses.

In France, enrolments were lower at 6,000 while Italy had 2,348 students, most of whom were studying gastronomy, jewellery design or fashion.

So how much money did these students spend annually? It is not certain. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) didn’t respond to request for information.

Government websites showed RBI’s numbers for 2018-19 but they appear ridiculously low. The RBI puts this figure at Rs 13,993 crore. If you divide the amount by 7,52,725 students, it translates to each student paying barely Rs 1.8 lakh per year.

One explanation could be that many students paid the fees without going through the RBI. Some may have got the money from their relatives staying overseas. Some got paid through funds available in those countries. Children of bureaucrats and ministers are known to receive scholarships from universities often through affiliates (direct and indirect) of businesses located in India.

But a conservative average of Rs 30 lakh per student adds up to a cumulative Rs7.5 lakh crore a year. The amount is likely to be much higher.

Now, compare this with the government’s 2017-18 allocation of Rs 4.83 lakh crore—for primary, secondary, colleges and universities.

Yes, the amount is higher than the Rs 3.34 lakh crore in 2011-12 but adjusted for inflation, the allocation for 2017-18 is lower.

While ‘real money’ for education declined, the government increased the number of primary schools by 72 percent over these six years, senior secondary school by 48 percent, colleges by 15 percent and universities by 55 percent.

Money should have been doubled over the six years to keep up with the expense but the government reduced funds.

India ends up creating more jobs – often for better-paid teachers -- and students end up spending a lot more overseas when this could have been done in India for Indians and mostly by Indians.

India could have been a great hub for education – it used to be one when Nalanda and Takshashila were around 2,000 years ago—but it isn’t.

It prefers to play politics instead, by dumbing down standards at schools, allowing sub-standard students in colleges, and burdening prestigious institutes like IIMs and the IITs with conditions like reservations, worse, it now wants reservations for teachers but that is for another day.

If education is the bedrock of a country’s future, India’s policymakers have all but wrecked it. The quality of education in most government schools is abysmal and policymakers celebrate new institutes and courses, without providing for them. They prefer to keep other countries happier instead.

(This the second article in a three-part series on the state of education in India.)

The author is a consulting editor with Moneycontrol

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.