Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is a boon for Indians for everything from buying pizza to paying bills. But for banks, non-banking finance companies and fintech companies, this means a steady deceleration in income from fees and charges because UPI generates zero revenue.

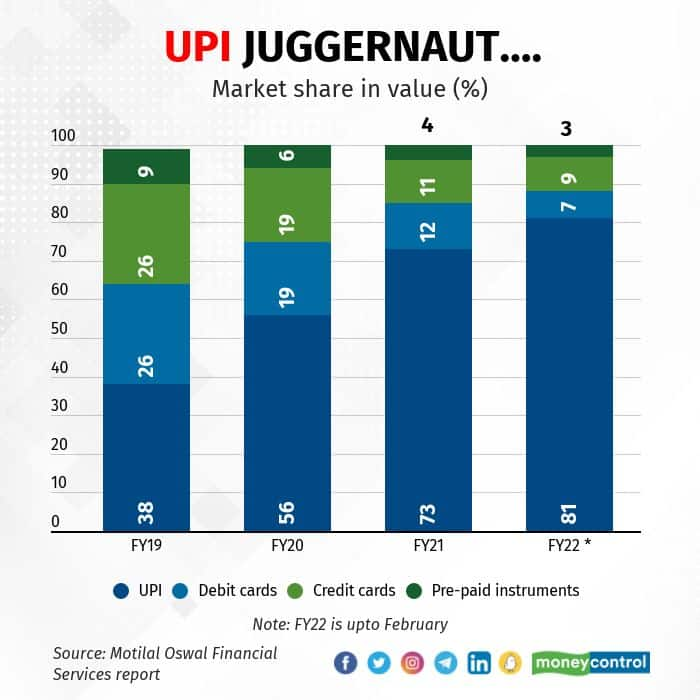

As the share of UPI grows in the overall retail payments pie, payment processing agents will lose out on revenue over time, analysts said.

“The shift in merchant payments towards low-yielding form factors such as UPI, coupled with rising competitive intensity across payment modes, is driving the overall payments fee yields lower across the ecosystem,” HDFC Securities analysts wrote in a note.

UPI is a real-time payments system that facilitates the instant transfer of funds between bank accounts. The platform was developed by the National Payments Corporation of India, an umbrella organisation that operates retail payment and settlement systems in the country.

In February, UPI accounted for about 80 percent of the total retail digital payments by value. Digital payments here exclude net-banking routes such as IMPS and NEFT, which process large-sized transactions and recurring payments such as equated monthly instalments of loans in addition to other retail payments.

The share of UPI in person-to-merchant payments widened to 42 percent in the first nine months of FY22 from 28 percent in FY21.

In 2019, the government cut the merchant discount rate (MDR) on UPI transactions to zero to encourage greater use of the digital payment system. MDR is a charge paid by merchants to payment service providers for the infrastructure to give customers digital payment options.

Widening share

In February, UPI accounted for a little over half the share in person-to-merchant transfers, data shows. The share of UPI is expected to increase as more merchants adopt it as a digital payment mode.

“UPI will continue to grow but the disproportionate growth we have seen so far may become more stable,” said Nitin Aggarwal, an analyst at Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

Banks have a dominant share in the MDR payment pool as card issuance and usage are largely through them. Banks can charge MDR on card-based payments and other digital modes.

Analysts estimate that the fees collected through cards and other payment modes account for at least a quarter of the total fee income of banks. This is now threatened by the surge of UPI.

Take the case of Axis Bank. The share of retail card fee income in overall fee income has come down to 1.9 percent in the third quarter of FY22 from 2.5 percent four years ago.

For State Bank of India, the country’s largest lender, UPI users have increased to 175 million in Q3 from 87 million two years ago. UPI’s share in remittances has also been rising and remittance charges contribute to about 25 percent of fee income for SBI. True, UPI has acted as a customer acquisition tool for SBI’s YONO app, but its usage has meant forgoing revenue too.

While banks have multiple streams of revenue, fintech companies such as Paytm suffer intensely due to the MDR waiver. UPI’s rise has been a big factor in Paytm’s troubles convincing its investors about its future revenue.

The outlook on payments revenue isn’t clear. In December, the Reserve Bank of India said it would revisit the charges involved in various digital payment modes through a discussion paper. The intent is to keep payment costs reasonable for customers so that the adoption of digital payment modes is not hindered.

Market participants said the RBI could allow a nominal MDR on person-to-merchant payments involving UPI but may bring down charges levied currently on card swipes.

A lot depends on whether the rules on MDR will be changed for different payment methods. Until then, most payment processing agents have a tough road ahead. Given their multiple streams of fee income, banks are perhaps among the least affected.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.