As the Delhi poet Zauq would say, Kaun jaye Zauq par Dilli ki galiyan chhor kar, for Lucknow-born Rana Safvi, 67, Delhi would become her home and her muse. When she was 55 years old, she moved back to India after living in the Middle East for a decade, teaching history in schools. “Delhi beckoned me,” says Safvi, who went on heritage walks and thought of writing one history of Delhi, about all the monuments in one book. But a trip to Mehrauli showed her how insufficient one book on Delhi would be. So, out came three books, a Delhi trilogy: Where Stones Speak: Historical Trails in Mehrauli, the First City of Delhi; The Forgotten Cities of Delhi; and Shahjahanabad: The Living City of Old Delhi and translations of Urdu accounts, Zahir Dehlvi’s Dastan-e-Ghadar on the 1857 mutiny to Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s pivotal piece Asar-us-Sanadid.

The author, scholar, translator and historian has written nearly 10 non-fiction books on India’s capital and, during COVID, started writing her first fiction novel, the recently released A Firestorm in Paradise: A novel of the 1857 Uprising.

Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)

Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)In this interview, she talks about Red Fort, Bahadur Shah Zafar, the 1857 uprising and more. Excerpts:

An illustration of Delhi's Red Fort in 1858. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)How was it transitioning from non-fiction to fiction?

An illustration of Delhi's Red Fort in 1858. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)How was it transitioning from non-fiction to fiction? In non-fiction, I know where I’m going. If I start from A, I have to end at Z. So, there’s a fixed trajectory in which I have to travel and I have to research that. But in fiction, when I started writing this [novel], the book and the characters just took hold of me. The biggest challenge for me was in finding the answers for the questions the characters were asking or dealing with the situations the characters were in. That challenge I never had to face in non-fiction [in which] I’d plenty of sources to work with. But, here, I was working with my imagination, plus a lot of accounts that I had read in Urdu.

You start your book with the Farsi/Persian couplet which we wrongly attribute to Kashmir and to Amir Khusro: Agar firdaus bar roo-e-zameen ast, hamin adto, hamin asto, hamin ast. Was it actually written for the Red Fort?Yes. While researching for my book on Shahjahanabad, and I’d heard earlier, too, that this verse couldn’t have been written by Hazrat Amir Khusro because it’s not in any of his diwans (collection of poems). Plus, it’s a very ordinary verse for somebody who wrote such complex poetry in Persian. He is, in fact, the first poet who has praised Hindustan a lot in his book Nuh-Sipihr (718-1318 AD), in which he talks of its climate, fruits, flowers, people, etc. This describes jannat (paradise) and Kashmir is called the jannat, and hence it [the verse] was used to refer to Kashmir. I was also told that Jehangir had said it about Kashmir and it’s written in the Black Pavilion of Shalimar Garden (in Srinagar). I went to Kashmir to look for it. Then, I went looking for Tahir Khan’s diwan in the National Museum archives, and found the sher was written for Delhi, for the Lal Qila, but again attributed to Amir Khusro. So, popular perception was this.

Verses by Saadullah Khan on the arches of Badi Baithak, describing the construction of Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)

Verses by Saadullah Khan on the arches of Badi Baithak, describing the construction of Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)But, a lot of 18th-19th century books mention it was written by Saadullah Khan, a wazir (minister) in-charge of the construction [of Lal Qila/Qila-e-Mubarak]. When Shahjahan inaugurated the Qila and held the darbar (gathering) at Diwan-e-Khas, he asked all the poets to write verses in praise of the Fort, which was conceived with a paradisiacal theme, with a river, Nahr-e-Bahisht (stream of paradise), trees, gardens…the Qila was built like firdaus (paradise/Eden). What we see today is a very depleted fort.

Nahr-e-Bahisht in Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)Your novel is essentially a romance novel between an imaginary daughter of Bahadur Shah Zafar, Falak Ara, and Mirza Qaiser, in the backdrop of 1857. You flesh out their characters with empathy. Were you trying to say something about the last Mughal?

Nahr-e-Bahisht in Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)Your novel is essentially a romance novel between an imaginary daughter of Bahadur Shah Zafar, Falak Ara, and Mirza Qaiser, in the backdrop of 1857. You flesh out their characters with empathy. Were you trying to say something about the last Mughal?The most popular image of Bahadur Shah Zafar is that propaganda photo taken by the British after he was imprisoned. But when you read Zahir Dehlvi’s Dastan-e-Ghadar (1914) and other accounts of the time, they are full of praise for Bahadur Shah Zafar and his vision. He was a Sufi saint. He was very inclusive and caring [followed the Surah Al-Kafirun or surah/chapter 109 of the Quran: ‘For you is your religion; for me is my religion’].

In Khwaja Hasan Nizami’s Roznamcha-e-Bahadur Shah, a diary of the emperor from around 1848-1852, more layers of his character started opening up for me. Apart from, of course, [William] Dalrymple’s narrative history The Last Mughal (2006), there is Syed Mahdi Husain’s academic book Bahadur Shah Zafar: And the War of 1857 in Delhi, which I used a lot of as well. These books and accounts showed me a character that was very different from the one people normally came to know. So, I wanted to do some justice to him.

Falak Ara is very mischievous and naughty, whatever she wants, she wants…to break all the rules. While (Mirza) Qaiser is very principled, for whom the question of breaking rules doesn’t arise. I thought that was a good foil to create chemistry between the two characters.

The throne in Diwan-e-Aam in Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)You’ve shown a syncretic society under Bahadur Shah Zafar, where people of all religion lived and celebrated festivals together. In an interview, you’ve said, when Bahadur Shah Zafar saw the English banishing people, the Muslim butchers and Hindu milkmen, because they were thought to be dirtying the city, he urged that his tent be erected next to theirs outside the city because he wanted to stay with his people.

The throne in Diwan-e-Aam in Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)You’ve shown a syncretic society under Bahadur Shah Zafar, where people of all religion lived and celebrated festivals together. In an interview, you’ve said, when Bahadur Shah Zafar saw the English banishing people, the Muslim butchers and Hindu milkmen, because they were thought to be dirtying the city, he urged that his tent be erected next to theirs outside the city because he wanted to stay with his people.That story is recorded in Dastan-e-Ghadar. Zahir [Dehlvi] was 22 years old during the uprising of 1857. He was a courtier and a disciple of Bahadur Shah Zafar and would regularly go to the Qila. He’s recorded all that. After the fall of Delhi, Zahir fled Delhi with his wife and family and was on the run until 1864, when he was given an indemnity by the Nawab of Rampur, and he could return to Shahjahanabad. He knew the power of the British. When he wrote this book in the early 20th century, just before he passed away, the British were still firmly in control. And the project of showing the Mughals as very bad had already started, as barbarian Muslims who interrupted India’s golden period. And that is why the Muslim period is called the Muslim period. Zahir Dehlvi talks of the badshah’s inclusivity.

In another book, an 18th century Urdu writer says, Diwali toh hum sabka tyohaar hai (is everyone’s festival). If you look at Mughal miniatures, in them you’ll find how Jahangir and Muhammad Shah played Holi, how Diwali was called Jashn-e-Chiragah (festival of lights, in Akbar’s court). I have not found anything that shows them celebrating Eid. There would be photographs of Shab-e-Barat and Nowruz, which is a cultural festival not a religious one, and comes from Iran. Similarly, Munshi Faizuddin [Dehlvi], one of the courtiers of Bahadur Shah, who wrote Bazm-e-Akhir (The Last Assembly) in 1885, was asked by the publishers that everybody who’s been an eyewitness to the Mughal court should record it. There were more reasons for these writers to praise the ruling British and not the badshah because he [Bahadur Shah Zafar] was no longer the badshah. He was in exile and, then, dead. So, their accounts are as accurate as they could possibly be.

Diwan-e-Khas in Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)Bahadur Shah Zafar and Nawab Wajid Ali Shah were a lot similar, the two were consumed by the arts, were dethroned and exiled. As a historical novelist, how much creative liberty can an artist take?

Diwan-e-Khas in Red Fort. (Photo: Rana Safvi)Bahadur Shah Zafar and Nawab Wajid Ali Shah were a lot similar, the two were consumed by the arts, were dethroned and exiled. As a historical novelist, how much creative liberty can an artist take?In historical fiction and novels, you can take as much liberty as you want. It can be just set in that period, and it becomes a historical novel. But I haven’t taken too many liberties because the historian in me was also cautioning me that this is not what could happen. Like, for example, I know all about the layout of the Red Fort, I know how well-guarded the harem was. So, I knew, it’s not going to be so easy for Falak Ara to just slip out to go and meet Qaiser or for Qaiser to just come into the Mahal. I had to find ways in which they could meet, so I used a medium of correspondence. Had I not known enough about the [Lal] Qila, I’d have made them come and go in and out of it as and when they wanted.

Imtiaz Mahal, one of the private apartments where the ladies lived. (Photo: Rana Safvi)

Imtiaz Mahal, one of the private apartments where the ladies lived. (Photo: Rana Safvi)I have used names which were being used in that time. The women wore khada pajama or churidars not gharara (like in Awadh). I have been very scrupulous about making sure that everything is in place, even the way the fictional characters speak and live in that same milieu as the historical characters. I’ve tried to do justice to all that because my main reason for writing this was also to showcase an era that has now been forgotten.

You don’t ascribe any religion to two characters, Hira and Hariyali. What was your motivation for doing that?Hariyali is like a sutradhar (narrator) because the book starts and ends with her, and she has access to every place in the city as well as in the Qila. For me, she was a kind of a metaphor for the city itself. Hariyali means prosperity, fertility, and she sells bangles, which is a symbol for suhaag (of matrimony/wifehood) in India, in north India at least. And Hira is shown as somebody with a very grey character. For me, one was a negative character and one was a positive character. I didn’t want to give any religion to them because they are generic people, you have good and bad everywhere. I wanted to keep them free, just to showcase human frailties, virtues and propensity to do evil.

The Siege of Delhi in 1857. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)In your works, you keep going back to a watershed moment in India’s history, which, our history books referred to as the Revolt of 1857. Later, we learnt about it as a Sepoy Mutiny and the First War of Indian Independence. But you’ve said it was not the first war of Indian independence. Could you elaborate on that?

The Siege of Delhi in 1857. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)In your works, you keep going back to a watershed moment in India’s history, which, our history books referred to as the Revolt of 1857. Later, we learnt about it as a Sepoy Mutiny and the First War of Indian Independence. But you’ve said it was not the first war of Indian independence. Could you elaborate on that? First of all, the concept of India as a nation was not there. He [Bahadur Shah Zafar] was the Shehenshah-e-Hindustan. And Hindustan was referred to as the northern part of India. I call it an uprising of 1857 because not everybody took part. For it to be a war of Indian independence, it has to be pan-India, but only the soldiers from Awadh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Delhi were fighting. Only a few rulers, like Nahar Singh of Ballabgarh, the Jhujharu, and the Loharu sided with Bahadur Shah Zafar, many didn’t. The rulers of Rajasthan didn’t. Many regiments came from Rajasthan to join the Indian sepoys, but the rulers didn’t. Rao Tula Ram of Rewari (Haryana) joined the uprising but Wajid Ali Shah was already in exile in Calcutta by then. Though his wife Hazrat Mahal joined. (Cawnpore/Kanpur’s) Nana Saheb and (Jhansi’s) Rani Lakshmi Bai joined. But it was not pan-India. It was just restricted to the Hindi patti (Hindi belt). The soldiers who came to fight against the Indian sepoys were the army of the Maharaja of Patiala. How else could the British, with a handful of soldiers, have ousted or won anything. In an army, if you go against your superiors, it’s called a mutiny. Later on, a lot of the ordinary, regular folks joined, too.

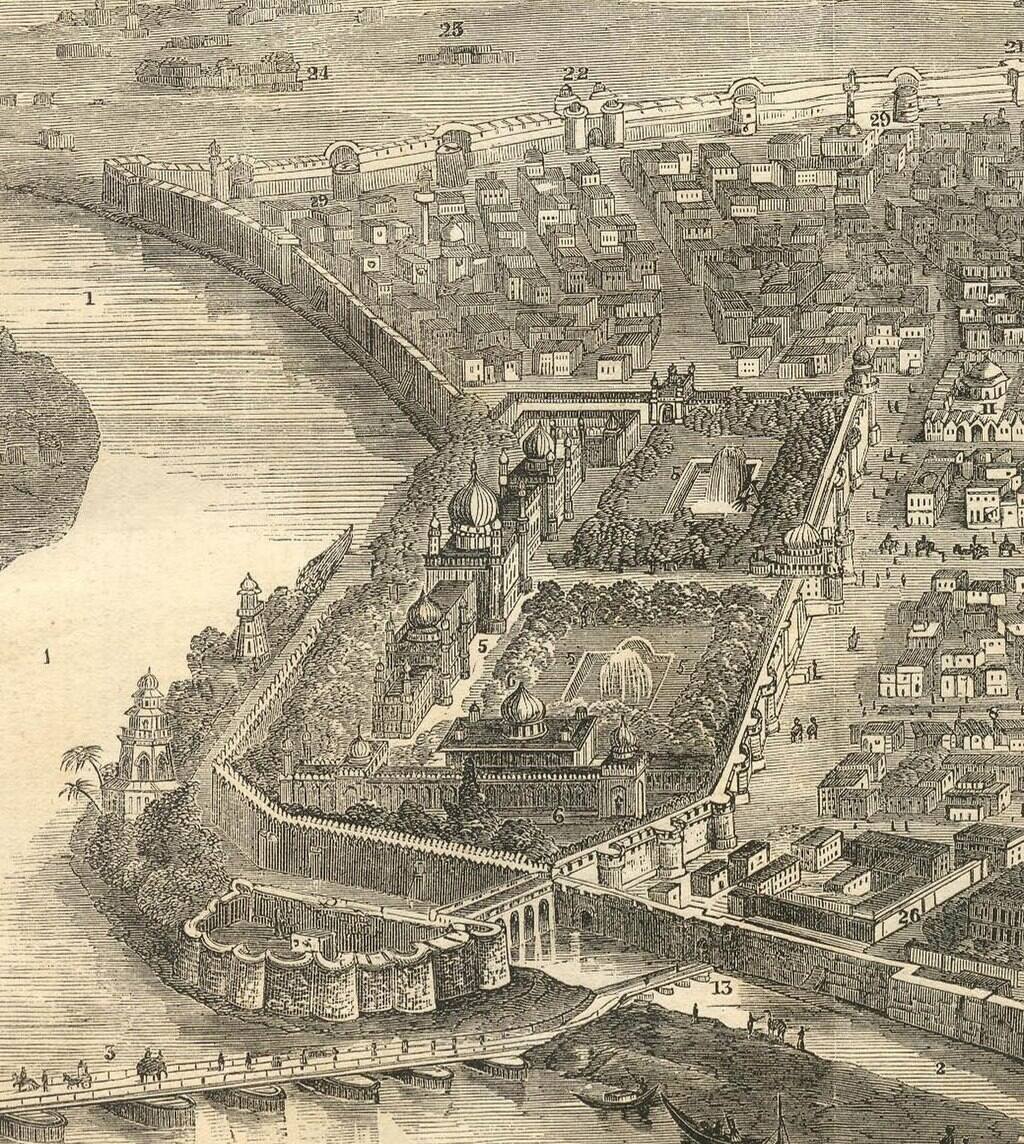

Bird's-eye view of the Red Fort (1785). (Image: Wikimedia Commons)We know Shahjahanabad as Old Delhi or Purani Dilli, but you’ve said Mehrauli was Purani Dilli.

Bird's-eye view of the Red Fort (1785). (Image: Wikimedia Commons)We know Shahjahanabad as Old Delhi or Purani Dilli, but you’ve said Mehrauli was Purani Dilli.When I was writing my book on Shahjahanabad, one of the first things that surprised me was that there were two Delhi Gates. Now, all the gateways in the city, whether in the old city or in Mehrauli, all had gateways which were named after the direction in which the respective road was going to. The Qila-e-Mubarak/Lal Qila has one Delhi Gate inside and one outside. So, it was very clear that what was Purani Dilli for them is what is south Delhi now, the poshest area, and Nayi Dilli (New Delhi) was Shahjahanabad. The Red Fort’s Delhi Gates were leading to Mehrauli. That’s what I’ve written in my first book, where the real Old Delhi was.

Delhi was named after Raja Dehlu (aka Dihlu/Dhilu), and whoever came to rule Delhi, whether the Mughals (Shahjahan shifted the capital from Agra) or British (capital shifted from Calcutta in 1911), they couldn’t rule for long. Could you tell us about the curse of Delhi?What do I say about Delhi’s curse…it’s a very popular, romantic belief because that’s the same thing as for Rome, the seven cities of Rome, and similarly, the seven cities of Delhi. Every ruler who came, tried to build his own capital and ruled around that, and they wanted to build their own citadels, (the walls of) some have survived, while others have not. For instance, Feroz Shah Kotla or Purana Qila, where nothing remains, because people gathered material, stones, etc. from the older cities for new constructions.

A decorative Meenakari art on the walls of the Lal Qila. (Photo: Rana Safvi)In your novel, there’s a mention of how the Slave Dynasty rulers, Qutubuddin Aibak, came and destroyed temples to build mosques. Didn’t it also happen during the Mughal era?

A decorative Meenakari art on the walls of the Lal Qila. (Photo: Rana Safvi)In your novel, there’s a mention of how the Slave Dynasty rulers, Qutubuddin Aibak, came and destroyed temples to build mosques. Didn’t it also happen during the Mughal era?See, power is something that, as they say, corrupts absolutely. So, this kind of demolition of religious buildings of the people before you was something to establish your power. [Art] historian Finbarr [Barry] Flood has written a lot about how the Spolia (stones taken from an old structure and repurposed for new construction or decorative purposes) was used for making other buildings, because there is a limit to how much of stones and building material you can procure. The stones from the Feroz Shah Kotla citadel were used in Shahjahanabad, the stones of Siri and Jahanpanah were used for building Feroz Shah Kotla. Hence, this kind of recycling was always there. It’s only when it comes to religion that people become very sensitive about it. People who are far more qualified than I am, like Finbarr Flood, have written a lot on this. Establishing of power is something that every monarch wants to do. Richard M Eaton starts his book, India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765 (2019), by describing two races, one by Mahmud Ghazni and one by Rajendra Chola, they both go and break temples. Rajendra Chola goes to Bengal and breaks a temple there. Mahmud Ghazni comes to Somnath and breaks a temple there. The only difference is that Chola brings back the idol and installs it in the temple in his kingdom. So, again, this was establishment of your authority. And the best way to do that is through religion.

In today’s time, there is a certain disdain for historians. How do you see your role, and that of translations, in rescuing history?(Smiles) Rescuing history…I like that. What I see my role as is something that happened very organically. I didn’t plan it to be so. I was just writing about history, about the things I was fond of and I researched. That got translated into writing books. I write a post almost every day on social media, on some aspect of history or the other. Once we have narrative history or popular history out in the public domain, the extent of misinformation and fake history reduces.

Rana Safvi in front of Asad Burj in the Red Fort. (Photo courtesy Rana Safvi)Can you debunk one myth about the Mughals?

Rana Safvi in front of Asad Burj in the Red Fort. (Photo courtesy Rana Safvi)Can you debunk one myth about the Mughals? Let’s talk of the Taj Mahal. How it’s being said that Taj Mahal was a temple, Tejo Mahalaya. Mughals were very scrupulous about writing their records, and this farman (decree) is there in Jaipur’s Kapad Dwara Collection [in the City Palace museum] that it was Raja Man Singh’s Mahal-e-Aliya (palace), and from his grandson Jai Singh I, Shahjahan got this palace in lieu of char havelis (four mansions). The farman even describes the char haveli. Nowhere does it talk of it being a mandir, it mentions Mahal-e-Aliya. That’s something I talk a lot about, of this farman’s existence. The Kapad Dwara Collection is under dispute so it’s not [publicly available] but it’s available in books. I have posted it many a time on Twitter (now X).

One Mughal dish that has survived and is relished today, other than biryani.(Laughs) Biryani came much later, the Mughals ate a lot of khichdi. In one of Aurangzeb’s letters to his son, he’s written that jaade mein khichdi se zyaada kuchh aur lazeez nahin hoti (no dish is tastier than khichdi in winter). Jehangir used to eat a lot of khichdi. Akbar’s Ain-i-Akbari even mentions khichdi ki tarkeeb (recipe).

One rarely known Mughal monument in Delhi.It’s not Mughal, but it belongs to Firoz Shah Tughlaq’s era (14th century), the Bhuli Bhatiyari Ka Mahal, a hunting lodge of Tughlaq. It’s near Karol Bagh, near Jhandewalan, and is a lovely place, but is in ruins now. Because it’s surrounded by dense thickets, people are scared to go there alone, but it’s a lovely monument.

Bhuli Bhatiyari Ka Mahal, Delhi. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)One thing you did not like about Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Heeramandi.

Bhuli Bhatiyari Ka Mahal, Delhi. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)One thing you did not like about Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Heeramandi.Oh my God! I liked Richa Chadha’s and Sonakshi Sinha’s characters. It was very well developed. But you are talking of Lahore, and Lahore had Punjabi culture, so much Urdu was not spoken in Lahore as it was spoken in Lucknow. Lahore didn’t have nawabs. Nawab culture was only in Awadh (present-day Lucknow). The makers have made a mishmash. Even the clothes, they looked beautiful but they were not accurate. I felt that he missed out on the opportunity of making a very sympathetic picture of the courtesans. Courtesans were very highly respected in that society but they never visited the zenanas (andarmahal/women’s enclosure) in households, unlike Manisha Koirala’s character who does so on Bakri-Eid, they [courtesans] stuck to the mardanas (outer apartments for guests and men), that was a big difference. Second, they have shown that everybody is out to run down the other, they could have shown some kind of sisterhood. Third, the songs. The Basant song… in Punjab and Lahore, it is Bulleh Shah and Baba Farid who are very popular, who’d sing Sufi songs in Punjabi. The zevar was over the top, no courtesan wore jewellery in such a [ostentatious] way. There were many things in which they (Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s team) did not research at all.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.