Among the many comedy of errors in this star-craved country, was one such a decade ago. In 2014, when non-fiction filmmaker Nishtha Jain won the National Film Awards (Film on Other Social Issues; Non-feature Film Editing) for her film Gulabi Gang, many audiences and the media assumed that she directed a Madhuri Dixit and Juhi Chawla film that had won. The air was eventually cleared. Two films, of the same name and similar subject, had released back to back. The prime difference was the form. Jain’s documentary, Gulabi Gang (2012), followed Sampat Pal-led group of women in Bundelkhand who, clad in pink sarees, fight the caste-based, patriarchal society and violent and oppressive system for women’s rights and empowerment. And the Madhuri-Juhi feature film, Gulaab Gang, was co-produced by Anubhav Sinha. It was because of Ship of Theseus director Anand Gandhi and actor-producer Sohum Shah that the documentary film was released in the theatres a week ahead of the Bollywood film. But, unfortunately, Netflix didn’t buy the film.

When the Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF) selected Gulabi Gang for its 2014 edition, the film also broke the jinx of the documentary filmmaker who had been making non-fiction films for close to a decade at the time, having screened in 200 international festivals but was yet to open her account at home. To return to MIFF, this year, with another film must feel like “homecoming” for Jain, whose internationally-acclaimed documentary Paat Katha/The Golden Thread, is competing in the International Competition Section: Documentary, in the ongoing MIFF, June 15-21, in Mumbai, Delhi, Pune, Kolkata and Chennai.

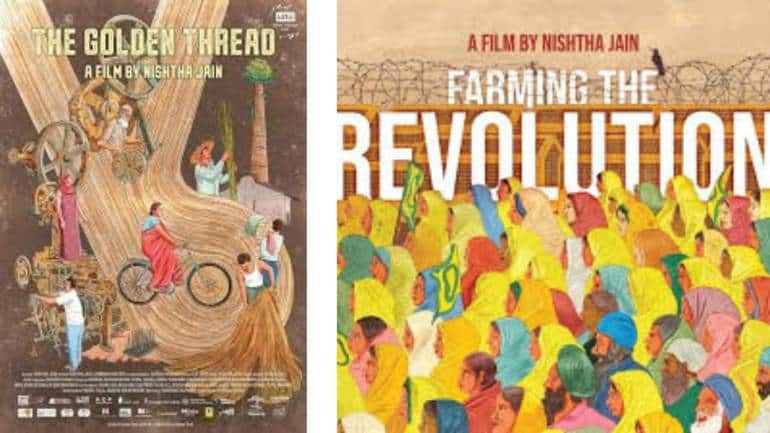

In The Golden Thread, Jain zooms in on two long-standing jute factories in Bengal’s districts, Wellington Mills and Hukumchand Mills. Her endearing, minute and detailed lens captures the beauty, the rhythm and rhyme in the grind and grime, the labour and toil, the million-crushed-dreams and the little joys of the workers engaged in spinning jute, hailed as the “fabric of the future”, from its bare kernel to the final sacks, ropes and more, passing through the myriad intensive stages of production and through the hands of its stakeholders and craftspeople, including the women, who work at home and work in the factory. The cycle never ends. While her film, The Golden Thread (2022), which is set outside of Kolkata, and looks at the lives of jute workers is screening at MIFF, her last film, Farming the Revolution/Inquilab di Kheti, on the farmer protests of 2020-21, screens at the International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala (IDSFFK), from July 26- 31. Both her films have won awards internationally.

Narrative documentaries, Jain said in one interview, “complicate the gaze and celebrate the plurality and complexity of our existence”. In the recent past, India has been seeing a surge in narrative or creative documentary films, which have been hogging the limelight at global festivals and award ceremonies. Jain has stood witness to the genre’s evolution because she’s a pioneer in narrative documentary storytelling in India and is among those who paved the way for the younger filmmakers to emerge and bend the rules of filmmaking.

In this interview, Jain speaks about why in her film, The Golden Thread, the factory, the jute fibre, and the industrial town were as much of characters as the workers of the jute industry, which was the birthplace of the trade union labour movement in India, and why human welfare must be made a crucial part of our environmental concerns. Edited excerpts:

How do you view your approach to your subject matter/films — is it journalistic, humanist, that of a historian, or an activist, as a catalyst for change?

What matters to me is what we will experience on the screen. So, the entry point of a film could be a place, a character, an event or an idea. What informs the film is my gaze, my worldview, and what I want to say through the film. As a documentary filmmaker, I’m an archivist, historian, and humanist.

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

You went to a film school after having worked. You went to both Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi and Film and Television Institute of India, Pune. Recently, Anurag Kashyap and Ram Gopal Varma said film schools are unnecessary to become filmmakers. What do you have to say to that?

You don’t have to go to a film school, you can also learn filmmaking by assisting filmmakers or you can learn by doing. A film school, however, gives a structure to your learning, exposure to world cinema, and a chance to make short films without the pressure of commercial viability. And if you don’t want to be part of the mainstream industry, film school is a better option provided you can afford to spend three or more years focusing on the craft.

Some filmmakers learn by assisting other filmmakers. For me, that was not an option. I was not interested in working in the mainstream film industry. I remember writing to a few filmmakers in Bombay, seeking to assist them but they couldn’t afford to pay me a salary that enabled me to make a move to Bombay. So, I preferred to go to a film school and was fortunate to get admission at FTII. But after graduating from FTII, I still had to take a job in TV to survive. Once I had some savings, I could find time to make independent films.

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

How did you come to the story of the century-old Hukumchand Jute Mill in Bengal and what triggered you to make the film?

I was screening the Gulabi Gang in Kolkata in 2014 when I heard about a violent clash between jute workers and management. At the time, many jute factories were also closing down. I wanted to know more about the industry which was the birthplace of the trade union labour movement in India. I got a chance to visit a jute factory and it was like time travel. It felt like I had entered a factory floor in the early industrial period — noisy and dusty, with century-old machines and fatigue and disappointment writ large on workers’ faces. However, it took me quite some time to decide on the artistic approach to the film. Imposing a character-driven narrative seemed false. After all, this was a story about the collective. For me, even the factory, the jute fibre, and the industrial town were characters and not just the workers. I wanted to explore the social and cultural life of the jute fibre.

The Golden Thread is the third film in a trilogy of your films on the working class after Lakshmi and Me (2007) and At My Doorstep (2009). The working class has more or less vanished from our screens, from the mainstream Bollywood films to the OTTs. Do you see your cinema as a voice for the working class and would that continue in the future?

We are living in a post-industrial world and the factory worker has little space in our world or our discourse which is largely to do with identity — religion, caste, gender. The jute industry is an eco-friendly industry but our concerns for the environment do not extend to the welfare of workers. If we don’t make human welfare part of our environmental concerns, the environment and climate crisis will only benefit the people who can profit from this crisis.

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

There are also few takers for working-class cinema, Anamika Haksar found it difficult to find a big distributor/OTT platform for her avant-garde film Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon. Considering celebrity personality cults, BTS publicity films and adapted true-crime docu-series have co-opted the OTT platforms in the name of documentary, what is the scope for actual documentary films like yours reaching the masses?

It’s difficult to take documentary films to the ‘masses’. One can hold community screenings but that requires time, equipment and money. It’s a full-time job. TV broadcast is another option that is not available in India. If you are not seeking to monetise, you can release your film on YouTube for free.

You bookend The Golden Thread with Phanishwar Nath Renu’s poem about jute mill workers and Hemanga Biswas’ Bengali revolutionary song Naam tar chhilo John Henry. You infuse poetry and music (folk music, workers singing in their free time as a pastime and protest music) into the drab reality of the jute mill workers’ life. How important is music for you, and selecting the sound design for this film, which is unusual for a documentary film, traditionally.

Sound design is crucial to all my films since most of them are experiential. I create the space and time through sound. Sometimes, sound works like music, like in The Golden Thread.

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

A still from 'The Golden Thread'. (Photo: Rakesh Haridas)

Similarly, your long-time lensman Rakesh Haridas’s stunning factory visuals of the reams of gold-like jute and the suspended dust particles seen in beams of sunrays entering the mill almost like one sees in the light the projectors throw at the big screen in pitch-dark cinema halls. The coordinated rhythm between machine and human movement in the factory and in the riverbeds, it’s all very cinematic. Such shots in ‘creative documentaries’, which look as if designed but aren’t, seem to be the new trend in Indian documentary films now, a breakaway from classic documentary. But you’ve always bent the rules and set your own template. Do you allow for a little play within the cinema verité setup?

We don’t design our shots nor choreograph the movements of our characters. We observe and shoot without changing anything in the setting. The Golden Thread is strictly cinema verité film. It’s the great camerawork, editing and sound design that makes the film cinematic.

Could you talk about the mill worker who doubles up as a godman at night? He’s quite an interesting character.

He’s a faith healer. To survive he has to work in the factory. He has customers visit him all night. I found it interesting that everyone in the area depended on the jute mills for their survival.

How much of a barrier was the language while making this film?

There was no barrier, workers spoke Hindi.

Farmers reading Trolley Times in a still from 'Farming the Revolution'. (Photo: Akash Basumatari)

Farmers reading Trolley Times in a still from 'Farming the Revolution'. (Photo: Akash Basumatari)

Congratulations on winning the prestigious Hot Docs award (presented by the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival) for Farming the Revolution, a film shot over 135 days about the farmer’s protest on Delhi border. At what point did you feel it was important to make a film on it?

I have been following the protests against the farm laws since June 2020 when the farm laws were presented in Parliament. The farmers arrived in Delhi on November 26 and we began filming two days later. We didn’t know when we began filming, how the protests would pan out, or how long they would last. They were epic in size and I hadn’t seen anything like this kind of solidarity or care before. There were several other filmmakers as well filming at the same time.

How different was the experience of making Farming the Revolution, unlike the other documentaries where you go with a certain idea of how you want to see the movie take shape, here the story was unfolding in front of you, with no end in sight?

We persevered with the farmers and kept filming till they won and returned home.

During the closure/merger of Film Division with NFDC in 2022, you told me how the option left for documentary filmmakers was to go to international funders with ‘begging bowls’ and they might have a say in the film shapes. Did that happen with The Golden Thread?

International film funders don’t interfere with our films. But interference could come from broadcasters. And, of course, the co-producers might give their suggestions and opinions.

No changes were made in The Golden Thread for anyone. But one of the broadcasters would have been happier with a character-driven film.

Talk a little about Bitchitra Collective, the Indian women and non-binary documentary filmmakers’ collective based in India and the US. We hear you gave the collective its name.

Yes, I take the credit for its name but I’ve been too busy with my films and I haven’t been able to give it the necessary time. Hope to be a little more active in the future.

You, along with fellow Jamia Millia Islamia alums Shirley Abraham and Amit Madhesiya (Cinema Travellers) were on the Oscars jury for the 2021 edition; would you attribute that as contributing a little towards the shortlisting of Jamia graduates Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Sen’s Writing with Fire in the Best Documentary Feature category for the Academy Awards that year, that was a first for India?

There are more than 3,000 members in the documentary section of the Academy. It’s mandatory to watch a minimum number of films before you can vote. In the last round, all active academy members can vote for the documentary nominees. The majority of the voters are still Americans. So, I don’t think our induction into the Academy influenced their nomination.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.