In Odia writer Bamacharan Mitra's 'The Holy Banyan', a four-generations-old acre-wide banyan planted to promote peace in neighbouring villages falls prey to politics and one-upmanship. In Rajasthani storyteller Vijaydan Detha's 'Countless Hitlers', farmers high on the promise of their newly acquired tractor crush a promising youth by the side of the road. In 'The Prospect of Flowers' by Ruskin Bond, an old English lady meets a worthy mentee to pass on her love of—and books on—Himalayan flowers just in time. The stories, written in different languages and by authors from different parts of the country, are among the hundred that have found their way into a comprehensive—if not exhaustive—anthology of Indian short stories titled '100 Indian Stories: A Feast of Remarkable Short Fiction from the 19th, 20th, & 21st Centuries', edited by AJ Thomas, a writer, translator and former editor of the Sahitya Akademi’s bimonthly English-language magazine Indian Literature.

This anthology of Indian stories in English translation, though remarkable in its scope, is hardly alone. In just the last 25 years, for instance, we have seen translators from Shanta Gokhale to Daisy Rockwell (see her translation of stories by Upendranath Ashk and Krishna Sobti as well as the International Booker winning 'Tomb of Sand') and Ministhy S giving the English-reading world a glimpse into the works of Indian writing stars. The late Lakshmi Holmström was widely regarded for bringing Tamil literature to the world through her English translations, from the 1990s. And the work continues. Apart from '100 Indian Stories', anthologies of translated Indian stories such as 'A Teashop in Kamalapura and Other Classic Kannada Stories' and 'Maguni’s Bullock Cart and Other Classic Odia Stories' have released already in 2025.***

'100 Indian Stories: A Feast of Remarkable Short Fiction from the 19th, 20th, & 21st Centuries' editor Thomas has previously translated and edited 50 stories in 'The Greatest Malayalam Stories Ever Told'. And yet, one can imagine the many challenges the present volume would have posed for him. For one, 100 Indian stories may sound like a lot until you start putting together an anthology. The sheer range, regions, styles and languages to pick from can get overwhelming. Add to that the unenviable task of selecting a time frame—for when the stories were published—that's neither so narrow nor so broad as to lose relevance or general interest. Then consider the challenges around finding good English translations from multiple Indian languages and figuring out how to organize the stories in the collection—by chronology, language, literary movements, theme, or form? Should satires sit next to comedy and horror, or would each get its own section? Should stories from the Little Magazine Movement of the 1960s and '70s sit next to Dalit Literature or should they be compartmentalized within the volume for better understanding? Should there be notes explaining the movements and summarizing the greatest works and the impact they had for each segment? Or should all explanations and notes be limited to the end of the book?

Indeed, almost anyone would baulk at the challenge of culling and presenting just 100 tales for a meaningful volume on Indian stories in English translation. A task that requires more than a passing familiarity with—if not encyclopaedic knowledge of—Indian regional literatures, to say nothing about the kind of deliberations that would be necessary to ensure representation of all the regions and the multiple languages and dialects used there. Think of the literary greats that such an editor must—of necessity—leave out. Take the example of Hindi writing in just the 20th century: Munshi Premchand, Nirmal Verma, Krishna Sobti, Mohan Rakesh, Raghuvir Sahay, Mahadevi Verma, Bhisham Sahni, Upendranath Sharma Ashk... whom would he leave out? Because leave out he must, to accommodate the key writers from the 23 other languages recognized by the Sahitya Akademi. Now, consider the (not small or even diminishing) challenge of forever having to justify the (often difficult) choices made to cull the number of stories down to just a hundred. How would he justify picking a story by Nirmal Verma but leaving Upendranath Sharma Ashk out of the collection of 100?

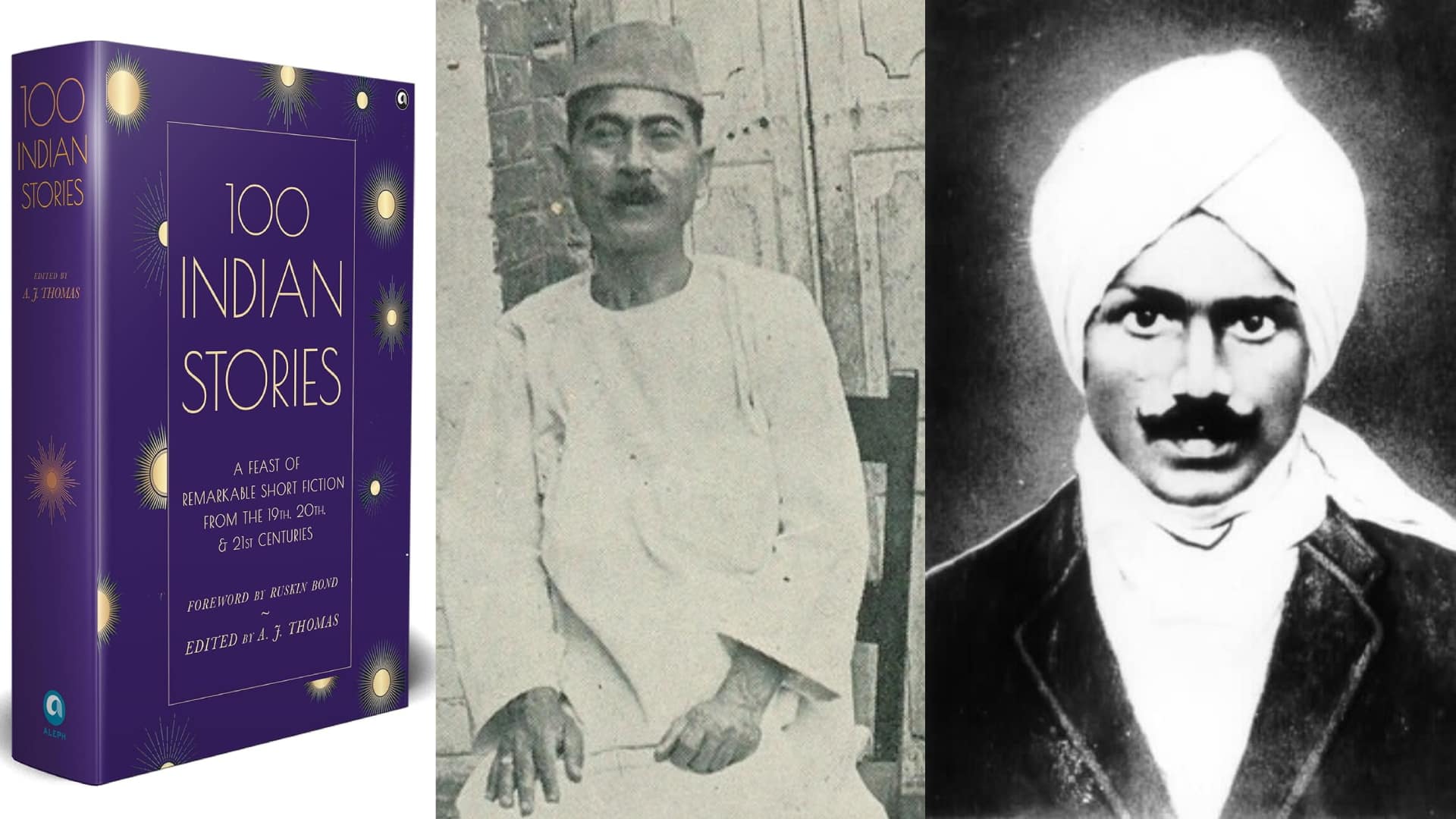

Cover of '100 Indian Stories' edited by AJ Thomas; Hindi writer Munshi Premchand; and Tamil author Subramania Bharati. (Author images via Wikimedia Commons)

Cover of '100 Indian Stories' edited by AJ Thomas; Hindi writer Munshi Premchand; and Tamil author Subramania Bharati. (Author images via Wikimedia Commons)

Speaking to Moneycontrol over the phone, editor AJ Thomas said that you don't explain the choices, you simply can't. Instead, you work with the knowledge that 100 is a tiny number when you're talking about great short stories from around India and hope that there will be more volumes of remarkable tales from around India.

Indeed, '100 Indian Stories' reads a bit like a sampling menu; a taster for stories from different regions, different writers and different translators. If you've read some of these writers or stories before, perhaps just revisiting them or the translations in this book could be worth your while. For the writers and stories you haven't encountered before, expect to find some surprises and some rabbit holes you might want to explore more at your own pace.

Even just flipping through '100 Indian Stories', you see that Thomas has limited his take in the volume to brief write-ups at the start and finish. In an introduction to the anthology, he offers an explanation for the time frame of the stories. The anthology begins in the late-19th century because that is when the short story format started to take root across India, brought here by European missionaries. By the 1930s, the Progressive Literature Movement was producing stars like Munshi Premchand with their stories falling squarely in the realm of social realism. After Independence, and as the decades rolled on, other forms of modern and post-modern literature found expression in the short format.

Thomas has also elected to keep the presentation as simple as possible. For instance, the stories in '100 Indian Stories: A Feast of Remarkable Short Fiction from the 19th, 20th, & 21st Centuries' are arranged chronologically, by the birth year of the author, with stories by writers like Subramania Bharati, Rabindranath Tagore and Munshi Premchand—born in the 1800s—occurring among the first 10 stories, and the writings of contemporary writers like Shashi Tharoor, Vivek Shanbagh, and Nagaland-based writer Avinuo Kire coming much later in the volume.

Satires sit cheek-by-jowl with folktales and fables in the collection, and stories originally written in Assamese, Odia, Bengali, Tamil, Urdu, Hindi, Kannada, Telugu, Portuguese (Laxmanrao Sardessai's 'The Gold Coin' and Vimala Devi's 'Job's Children'), English, Malayalam, Kashmiri, Punjabi, Gujarati, Rajasthani, Marathi, Konkani follow each other, creating a feeling of plenitude, but also a kind of level-playing field, helped along by some really good translations by people like Shanta Gokhale, Lakshmi Holmstrom, Neerja Mattoo, Poonam Saxena, Arunava Sinha, Rita Kothari, Leelawati Mohapatra, Khushwant Singh and Thomas himself.

In a way, Thomas agrees he may have been preparing for editing just this kind of book for decades—even before he began editing Indian Literature at Sahitya Akademi in Delhi. Thomas did his MPhil between 1989 and 1991 at the then newly opened School of Letters (Mahatma Gandhi University) under Professor UR Ananthamurthy, Vice Chancellor, "where Malayalam and English students were joined in one batch (back then) for creative study... with Western theory and Eastern aesthetics together".

UR Ananthamurthy (Image credit: HP Nadig via Wikimedia Commons 3.0)

UR Ananthamurthy (Image credit: HP Nadig via Wikimedia Commons 3.0)

While Ananthamurthy himself was an "excellent teacher and inspiring writer", Thomas also remembers learning a lot from the School Director Narendra Prasad and Professor V.C. Harris. Both Thomas' MPhil and PhD theses were on translation studies; “Modern Malayalam Fiction and English: An Inquiry into the Linguistic and Cultural Problems of Translation" for his PhD, and “Seventeen Contemporary Malayalam Short Stories: Translation into English with an Introductory Study” for his MPhil.

Thomas says his "life changed" in the early 1990s, when Rubin D'Cruz, assistant editor at the National Book Trust engaged him as copy editor for their three-volume anthology 'Masterpieces of Indian Literature', edited by Dr K.M. George, in their project office at Thiruvananthapuram. Thomas' first book of translated stories, 'Bhaskara Pattelar and Other Stories' by Malayalam writer Paul Zacharia came out just two years after he completed his MPhil in Kottayam, Kerala.

In late-1997, Thomas found himself in Delhi, being interviewed to work with the 'Indian Literature' magazine of the Sahitya Akademi. Just before the interview, he remembers getting a call, inviting him to translate Paul Zacharia's stories, to form a collection (the English title of the translated work: 'Reflections of A Hen in Her Last Hour and Other Stories') into English. Thomas landed the job at the Akademi and took up the translation gig, as well. (Thomas has included his translation of Zacharia's 'Reflections of a Hen in Her Last Hour' in 100 Indian Stories.) He later co-edited the two-book, four-volume 'Best of Indian Literature' carrying the best of short stories, poetry and literary criticism published in 'Indian literature' over a half-century from 1957 to 2007 to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Indian Literature.

At Sahitya Akademi, Thomas said he got to interact with some of the stalwarts of Indian literature in multiple languages, including Vijaydan Detha whose stories have since been adapted for films like Shah Rukh Khan starrer 'Paheli'. Thomas got to understand from them firsthand about their motivations, their methods and their craft. He also got a feel for placing literatures from multiple regions, with their multiple influences, in the same magazine issues.

Reading '100 Indian Stories', you get the sense Thomas has also exercised a skill that editors typically pick up over years on the job: how to get out of the way of a good story, and a good story collection.

One final observation: Towards the end of the book, Thomas has given notes on the authors - some of whose command over the short story format is so compelling that it's a shame their names are not as well-known globally as, say, American writer Edgar Allan Poe or Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges. Perhaps this could change dramatically in the 21st century, with more volumes of Indian stories translated in foreign languages - not just English - for the world to read?

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.