Author Devdutt Pattanaik has carved a niche as a modern-day interpreter of mythologies. In 70-plus books, starting with 'Shiva: An Introduction' in 1997, Pattanaik has culled lessons for business and for life from Hindu mythology, Jainism and other mythologies. Pattanaik's latest book, 'Ahimsa: 100 Reflections on the Harappan Civilization', is a continuation of this work though the source material is decidedly different from his usual reliance on Hindu, Jain or Buddhist mythologies.

In an exclusive interview with Moneycontrol in late September, Pattanaik explained why he continues to draw upon mythologies even after 27 years: "Mythology is like a tool kit which is developed over thousands of years across all cultures; it communicates to us through stories, symbols, rituals. And if you study mythologies, you understand the human mind. That's what interests me. How do human beings approach life? How do they make sense of the world? That's why I write so much on mythology."

That Pattanaik has turned his attention to Harappan mythologies in 2024 is no coincidence - the release of 'Ahimsa' coincides with the centenary month of the Archaeological Survey of India's discovery of an ancient urban civilization at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. Yet even as Pattanaik read works by history and archaeology scholars like JM Kenoyer and Mayank Vahia as research for this book, he maintained his own mythological filter. The result is a selection of stories and conjectures around objects, symbols and organizations in the Harappan culture.

"I was interested in Harappa because you don't have stories from Harappa, but you have architecture and art. And I asked myself what was the mythology of these people? How did they imagine the world? How did they see the world?" Pattanaik said in the exclusive interview to Moneycontrol.

Pattanaik spoke at length about his take on the Harappan Civilization, the usefulness of mythologies in the present day, why he thinks historians prefer ideologies to mythologies, why he illustrates his works, and whether there is any similarity between Harappa's unicorn seals and unicorns of the start-up world today. Edited excerpts:

Mythology and Harappan Civilization - what got you interested to explore this side of India's ancient past?

I was interested in Harappa because you don't have stories from Harappa, but you have architecture and art. And I asked myself what was the mythology of these people? How did they imagine the world? How did they see the world?

What struck me about Harappa was the fact that they were obsessed with standardization. They were obsessed with modular thinking. Everything was very well-organized; everything was well-measured. Everybody says what a wonderful civilization, but it really feels like an industrial unit where everything is tightly controlled. It didn't feel in many ways a standard Indian idea (where diversity is in evidence everywhere).

So I said, let me just read this. And the more I went in, I realized these Harappan cities were trading communities. They were trading with the Middle East. They were exporting Lapis Lazuli from Afghanistan, Carnelian from Gujarat. And it was going up the Makran coast towards the Persian Gulf. Oman has Harappan seals. You realize it is a trading community, and like all trading communities, they prefer standardization.

But outside the cities, there is a lot of diversity in the farming practices, in the animal husbandry practices. We focus too much on the cities and we forget about the villages which support cities. These were the ideas I wanted to share with the world; and how a civilization could last for 700 years with very barely any signs of violence.

This book is different from some of your other books, in that your source material is different. Can you tell us a little bit about the research that you did for this book and how long did it take you? And it is not a coincidence that this book is coming out in the same month when we celebrate the centenary of the ASI finding the Harappan cities in the 1920s?

No, it's not. I love writing, I love researching, I love mythology, and I have always been wanting to write on Harappan mythology because when I read archaeologists and historians, they completely ignore what they call ideology. Nowadays they're using this word ideology in a very dismissive way. But they really don't get ideology because they don't know their own ideology. Unless you know your own ideology, you cannot understand other people's ideology.

When I heard about this centenary a couple of months ago, I got very excited. But I didn't realize what I was getting into, because unlike Ramayana and Mahabharat and the other mythologies that I have been studying for decades, this I had sort of had a little information and I just assumed that was enough. But then I had to listen to scholars.

My research involved reading as many books as I could, research papers of archaeologists and really it's the archaeologists and lots of amateur archaeologists and scholars - there is Mayank Vahia who was formerly with Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. Then there is a young lady called Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay who has decoded the script very differently and using very lateral thinking. There are these archaeologists from the Archaeological Survey of India, Ajit Prasad. I can't remember all their names... Jonathan Mark Kenyore who works a lot in Pakistan... big scholars who have really done a lot of work, and they have published all their papers, shared it on videos on YouTube and channels. They shared it with the world on Harappa.com, which does it very beautiful, and they really exchange information - and I wanted people to know their work.

But my focus was on mythology, and not so much on the length of the brick and length of the street and the number of wells... That's important as data from which get this knowledge of how they imagined the world, and I wanted to tell people how the Harappans probably imagined the world and why we should look at the monastic-mercantile model in a little bit more detail because that is more Indian. And why we should avoid using Western words like citadel and acropolis and blocks, and use words like graam, kula which are Indian words which of course came later.

This research of about 6-8 months... I have mentioned as many scholars as I could remember, whose works I have referred, to at the end of the book. The original part of it is the mythology part (that) I am focusing on. But all the data has been collected by so many scholars, so many archaeologists, historians, script decoders, astronomers, experts in agriculture... It's an amazing amount of work, which is not taught in schools.

What are the most fun lessons for businesspeople and economists from the Harappa civilization?

The biggest thing is the assumption about who managed the business: was it men or women? One of the things I noticed is that the powerful characters in these Harappan seals seem to be rather androgynous. They are wearing male costumes as well as female costumes, which means that the ones who controlled the ecosystem were people who gave up wealth, power and also perhaps gender. It is not impossible that the women managed the show at home while the men travelled on boats and did the actual moving around. The role of women I think needs to be highlighted.

The use of industrialization, the industrial production of beads and fabrics in warehouses - this has to be highlighted. It is fantastic how logistics was being managed.

The idea of gated communities. These were people who protected themselves with the walls and courtyards. There were multiple gated communities. In fact, Harappa is not a single city. It is a set of gated communities and your access to the gated communities was perhaps controlled using these seals.

These seals clearly deal with financial documents like revenue and licences, and that makes it very, very interesting. And how did they manage all this with minimum or no violence, and how are violence and non-violence linked to economics? It is about sparking thought and making you think differently about ancient civilizations. The fact that it starts in Gujarat and Haryana; today also we speak about businesspeople in Gujarat and Haryana. Maybe Rakhigarhi (in what is now Haryana) was more an industrial centre and the ports were there in Gujarat from where the ships sailed - Dholavira and Lothal.

You have some lovely drawings in the book... tell us about the one that inspired the title of 'Ahimsa'.

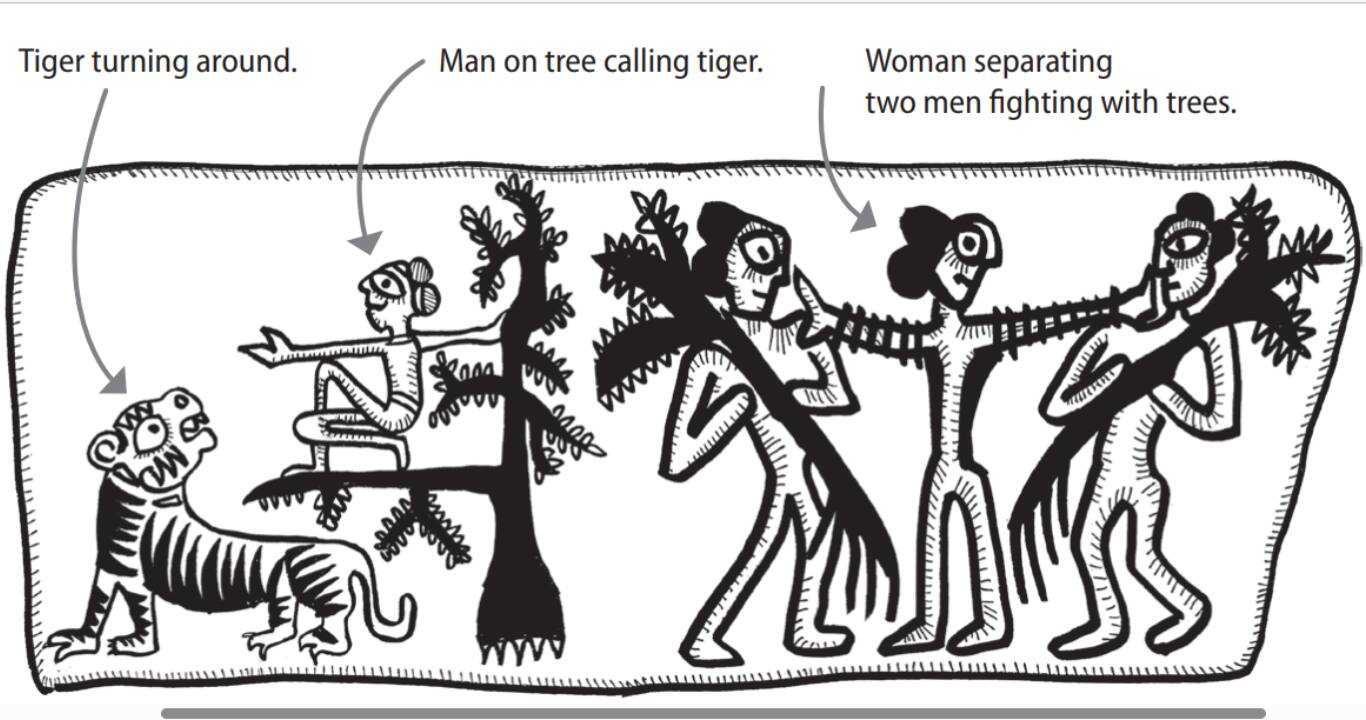

The images (in the book, inspired from carvings in Harappan seals, pots, tablets, jewellery) are very big, but the seals actually would be barely an inch. For example, if you look at this image from a clay tablet, you will see a woman separating two men from fighting. The two men are holding some kind of plants. It's like Sugriva and Wali fighting, but here they seem to be separated by someone wearing bangles, most probably a woman.

Illustrations by Devdutt Pattanaik in 'Ahimsa: 100 Reflections on the Harappan Civilization' (2024).

Illustrations by Devdutt Pattanaik in 'Ahimsa: 100 Reflections on the Harappan Civilization' (2024).

I would look at the interpretations, and they would always say it is men fighting over a woman. And I said that is a very patriarchal gaze. Could it be that the woman is separating the men and saying that violence and fighting is not good for business, but trading instead of raiding is what gets value for everyone?

And maybe she is talking about ahimsa and connecting with trade and nonviolence. And I said this is the ahimsa seal of Harappa. I said, so it doesn't start with Gandhi, but it starts with Harappa. And that is the idea which sort of sparked the title of the book.

Because nonviolence... how do you make money? You make money by hoarding wealth. You raid people, you plunder people or you trade. So you have a choice between raiding and trading. And I think Harappans realized this long, long ago. And they spoke of trading which is a nonviolent way of doing business rather than raiding.

Even today, if you see images of African mines and how mining takes place based on plunder, it's based on violence. It's not based on exchange of wealth. The idea that one company controls, has monopoly is a very hoarding practice. These are unhealthy practices. They lead to violence immediately.

There is a violent business which is promoted by modern industry and there is nonviolent business which is based on mutual benefits. And these are the ideas which perhaps were created by the old Jain and Buddhist merchants and monks long ago and even before that in Harappa; Harappa existed 1,500 years before Buddhism and Jainism.

So maybe these are old old Indian ideas, and I want to just propose it, it is very difficult to prove it or disprove it, but I want to propose that it is certainly not a patriarchal fight of two men fighting over a woman. That is a very pedestrian gaze.

You talk about the division of ideology versus mythology in 'Ahimsa'. Now, the stories you are pulling from for this book are typically seen as the preserve of history. So how does this divide apply to this book?

I have been reading a lot of historians and I realized that historians are very uncomfortable with the word mythology. They are afraid of things or matters of faith. They are afraid because, you see, a historian depends on material, artifacts, objects, texts and they have to make sense of objects, archaeological artifacts and texts. And in doing that, they are not really equipped to understand the imagination of people.

Nowadays they have started using word like imaginarium and ideology. They just don't want to talk of the word mythology. There is another word which is used in the humanities called social construct; anything but not the word mythology because their predecessors created this word called mythology which they said is not true and they started believing that mythology is something false and disturbs people and ideology is something better. This is just word politics that is very common in academia.

But every culture has a mythology. Historians have ignored mythology because they assumed it is religious and they were looking for a world where religion does not exist. And that is impossible.

I use the word mythology because it is the belief system of people, and beliefs can be secular, beliefs can be rational, irrational, they can be based on one God, many Gods, no God.

And if Harappa for 700 years was building cities, trading, having these seal systems, they obviously had a way of imagining the world. What is that mythology? What is that social construct? You can call it ideology, but ideology makes it sound very intellectual. It doesn't capture the rawness of human imagination. It sounds very like an intellectual exercise, a professor sitting and coming up with an idea. Nobody talks about tribal ideology. Ideology is always related to Marxism, socialism and all these European ideas.

So I wanted to know what was the imagination of the Harappans? How was it different from the imagination of Egyptians? How was it different from the imaginations of people who built the pyramids? How is it different from the imaginations of people who built tombs in Mesopotamia in what is called the Fertile Crescent?

The earliest cities in the world, the trading empires in the world - how did they imagine? I use the word mythology which, as I said, the academicians call problematic because they don't admit they themselves come from a mythology and they do not ever share their own mythologies which shapes their writings.

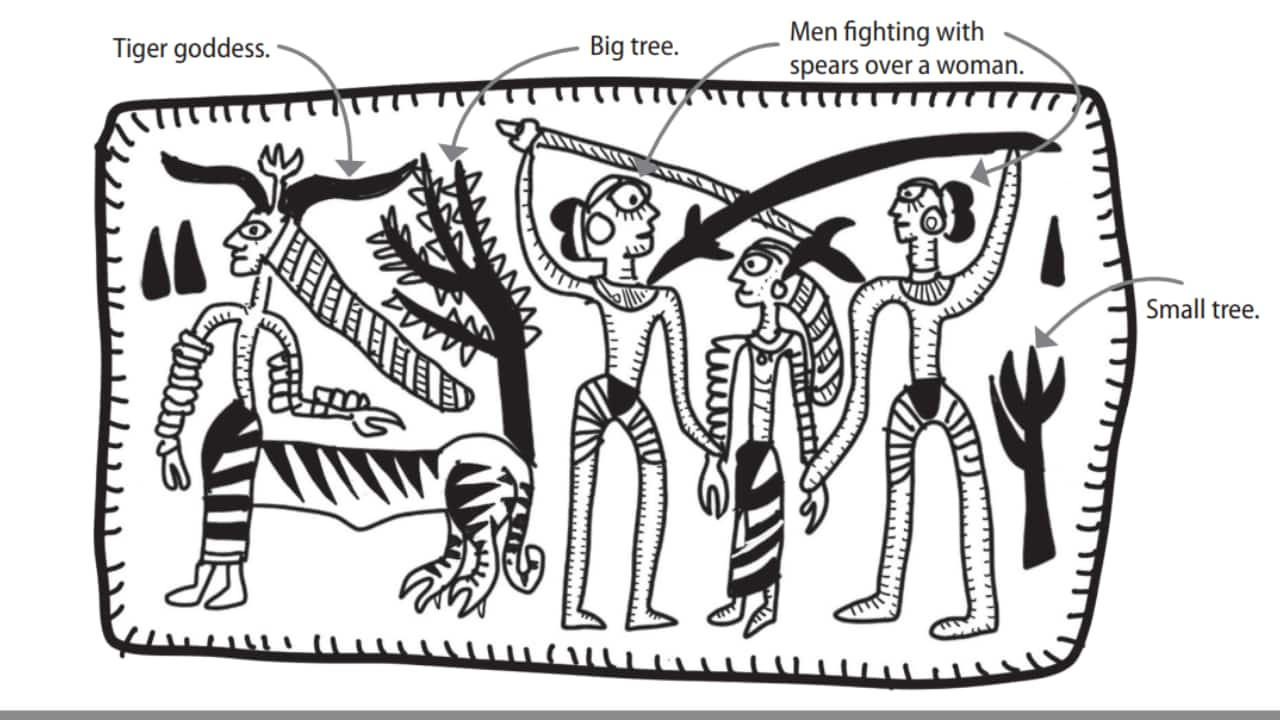

In the book, you have illustrations that show the difference between the Indus Valley Civilization and Sumerian art. Can you talk us through that a little bit?

The earliest cities we know were built in Sumeria. Now what is Sumeria? It is southern part of Iraq, the delta of the rivers Tigress and Euphrates. You find that these cities are not as organized as the cities in Harappan. They do not have this very clean architecture of roads, which are perpendicular to each other (in the Harappan cities). You have in the center of the city a temple and a slightly disorganized array of residentials around it. While when you see Harappan cities, they are very well organized, they are very well planned and there is no dominating temple as such.

The more you study the civilization, you realize it (the Harappan Civilization) is a highly collaborative civilization - very, very collaborative. There does not seem to be a king or chieftain or an empire, unlike in Sumeria. That's fascinating, you do not find gods. There is worship and veneration, but it lacks the kind of reverence to supernatural beings that is very evident in Mesopotamian writings.

Mesopotamian art shows a lot of violence, a lot of individualization, while Harappa shows very little or absolutely no violence, I can say. And it shows institutional thinking, not individual thinking. For example, all the seals seem to be carved using standard rules and these seals are found in distances of 500-1000 kilometres apart. Same seal, same design for 500 years. And look at this geography spread.

But when you go to Mesopotamia, you will find the seals which are of different materials by different people, with individual names, with different themes. A lot of diversity exists.

So it is very strange that today when you go to the Middle East, you see a highly homogeneous culture and you come to India and you see like diverse culture. But in the Harappan period, it almost seems that there was more homogenization in the Harappan side, the Indian side, and there is a diversity in the Sumerian side. So with time, things change.

It's interesting how that translates into the iconography of the place, the civilization. In the book, you talk about the Unicorn seals. Are the unicorns here in any way similar to the startup unicorns we talk about now?

When people use the word Unicorn, in their mind there is the Christian imagery of a horse with a single horn. The word Unicorn is a mistranslation of a biblical term and became a hit because in the medieval period, the idea of the Unicorn being attracted to the virgin innocent girl became very, very popular and it became a symbol of Christianity.

But in India, the word was ekashringa. Ekashringa many people believe referred to the rhinoceros, but we are not really sure. If you look at the Unicorn symbol in Harappa, some people think it is a two-dimensional image of a bison or a gaur, but it's not so because you actually have figurines with one horn. So this is a mythical creature.

Now the local communities seem to have used wild animals like an elephant to represent themselves (on seals). But when they had to work together, they needed a symbol that everybody could agree upon, and they could not agree upon a natural animal which they could see around them. So they came up with a mythical animal, one with a single horn and that became like the team that ensures collaboration and resolves disputes between different communities.

Eighty percent of the Harappan seals have this image (of unicorn/s). Some people suggest it's the bureaucracy. I believe, and I am hypothesizing, that these were regulators of the business. They were managing and creating the standardized patterns that you find across the civilization.

Illustrations by Devdutt Pattanaik in 'Ahimsa: 100 Reflections on the Harappan Civilization' (2024).

Illustrations by Devdutt Pattanaik in 'Ahimsa: 100 Reflections on the Harappan Civilization' (2024).

But they got their power not through violence, but through non-violence. Now what does that mean? These were people who were monks. These were people whose power came by renouncing wealth and power.

Even today we believe monks because they were orange clothes are supernatural, and then they are simple and they are fair and they are honest and they are connected to the divine, and everybody sort of follows the celibate monk. And I think in Harappa too, there were these celibate monks who may have been successful businessmen who at a height of their career, gave up their businesses and participated in a kind of a collective ecosystem of hermit regulators. And I think the Unicorn was their seal and symbol and they helped people.

The Harappan script is used in business financial documentation - in all probability, that's the direction in which the scholars are going - regulating such a business can either happen violently with a forceful feudal royal authority, or non-violently, as it has always happened in India, through monastic systems. So the Jain business community, the Buddhist business communities were controlled, managed, regulated, inspired by monks, who would also manage banking, settle disputes, enable negotiations, create networks, and I believe in Harappan. Something like this also existed, represented by the Unicorn.

Unicorn today means someone will make a lot of money for himself. I think the Harappan Unicorn was someone who enabled others to make money, so it is far more spiritual than the greedy things that we nowadays call ambition.

The merchant-monastic complex that you spoke about, there now seems to be a division between religion and trade. You are saying that back then there was a clear line of regulation?

If you see where the oldest Buddhist stupas and the oldest Jain images have been found, they are always found on trade routes. For example, the Buddhist caves of Bombay itself: Jogeshwari has caves, Kanheri has caves, and if you go towards the north, you have the Bhaja caves. Who funded these caves? Not kings, but merchants, collective merchants. Across Maharashtra, in Andhra Pradesh and Sanchi these was not built by a king, it was built by merchants. So there is clearly a merchant. Why would they give so much wealth to the monks? Because they obviously got something from the monks. What did they get? The monks were translators. They were literate people, they were educated people. They provided medical services. They provide rest houses. This we know very clearly from Buddhist literature, is not the Buddhist image that is 19th century construction, but scholars know that Buddhist monks played a key role in banking practices in Southeast Asia. Wherever Buddhism went, farming took place. You see large tracts of farms being built, and the whole idea was if farms exist, food exists. If food exists, they can pay the bhikshu and the bhikshu and Buddhism will flourish and therefore Dhamma will flourish. And therefore you find a close relationship between economics and Buddhism, economics and Jainism. And I am saying the same idea existed in Harappa.

We don't have to see it from a military point of view. Military way of making money is something which comes from colonizers. It comes from the British East India Company and nowadays with democratic nation states which use military to get markets. But these are very violent, dangerous ways of making money, never makes people happy. And traditionally in India it has the business had to associate with non-violence and non-violence was about enabling other people to make money. And I think these monks enabled it and they could do it because they genuinely did not collect wealth, not like some gurus of today who have their own private jets and private islands. But these were people, if you see the Digambara images of the Jainism, these were people who didn't. So you sort of trust people who don't own anything. And I think the unicorns perhaps represented these kind of people. and there it's very interesting you find these models across India, in temples of India where somehow in people trust monks. The church was the oldest banking institutions; they collected money. The Knights Templar started banking and they learned from home. They learned it from Jain traders in the 14th. So these ideas I wanted young people to understand through Harappa. Because when we talk of Harappa, everybody is talking about art and architecture. I'm like why is nobody talking about the economics, the business? It's a business community is trading with Middle East and doing import, export and logistics and financial documents. Nobody talks about that. They are somehow interested in looking for Aryans and Shiva and God. And I am like, really? That's like a politician who tries to divert attention from economics and politics and wealth management and focuses on useless issues.

Which methodologies are you drawing upon, and how are you sort of distilling some of these lessons from them?

All mythologies; you cannot study one mythology without by and ignore other mythologies because they are all sort of interrelated and they reveal, as I said, cultural truths, and then if you go deeper, they reveal something about the human condition, how our brain functions, how do we respond to challenges. For example, if you travel West, you come to the Middle East, you come to Arabia, you come to Europe, and then beyond this America. And these are the lands where we find a domination of mythologies which are monotheistic, one God, one truth. And from that land comes ideas like universalism: everybody should think in the same way. So even secular ideas like democracy becomes universalized. Everybody has to be democratic. Everybody has to believe in universal human rights.

So its equality, diversity, inclusion, everybody has to follow it. You see it in western mythologies. But you go to the east towards China, towards Japan and you study the mythologies of China and Japan and you see they don't talk about God as much. There is no one God out there controlling and telling you how to live your life. Instead you have walls being built and they don't like universal ideas, so they built a wall around their cities and within the walls they follow filial piety. Now that's the way you see in Japan, China, Korea. They tend to be xenophobic. They love hierarchies, they respect people in positions of power. So you find a very different language. Then you come to India, and the stories are again very, very different because India talks about rebirth and that is what is unique about Indian thought and rebirth and karma and action and reaction and consequences. Now you suddenly understand how why the West's business practices are very different from, you know, Chinese business practices, Japanese business practices. Why is India looking so messy? Because it's a different mythology.

Could you unpack that a little bit more in terms of, you know, the context of business? How do you sort of distill lessons from mythology to business?

So think of this; everyone who does an MBA is told have a vision statement and you have to do have a mission statement. And if you see how businesses stock, they say we bring value to the customer and shareholder value. They never talk about the consequences of their actions. What is the consequence of establishing an industry? What is the price to nature? It is only now when we are talking about pollution and climate change that people are even raising these issues. The idea that an action can have a reaction is not there in Western thought and therefore they are always talking of progress. They never talk of the price of progress. The word progress assumes whatever they do is good. But Indian thought would talk about karma. So they will say if you cut a tree, what are the consequences of cutting a tree? You need to cut a tree, otherwise you can't build a home, you can't have firewood, you can't do so many things, you cant have furniture. But what are the consequences of cutting a tree? Now that idea does not exist in the West. So they talk about democracy without talking about the price of democracy. They talk of secularism as a good thing. So secularism becomes so in business practices.

You had globalization being talked about 20 years ago, when I started my career; one way of thinking World Wide Web, globalization. Today we are every country is talking nationalism because that one idea didn't work.

This homogenization and standardization didnt work. And now we are using words like diversity and inclusion. This word was not used 20 years ago when globalization was being talked about. So this idea, one versus many, static versus dynamic, it is happening around the business because most business people, they are sort of overwhelmed by Western narratives and and Western narratives really are the same space where colonization came from and industrialization came from.

And you see that impact in the stories. The stories reveal why things work and why things don't work.

So we are circling back to the original way of thinking really that you sort of find in Indian mythology. Is that right?

Yes, because India has always dealt with diversity. Every form of diversity: tribal diversity, community diversity, religious diversity, linguistic diversity, economic diversity, diversity of skills and capabilities. It is not based on homogenization of society. Think from a business point of view: standardization is efficient. So stand efficiency, what efficiency? So you want standardization, but standardization is anti-diversity. So you suddenly realize diversity means inefficiency. And this is not an idea that is discussed in business schools because the whole problem with diversity is it's inefficient. You have to invest more resources to talk in many languages, to deal with people with different cultures, to talk about different gender. All these things cost a lot of money.

You will never see Apple sharing its data with Google or now X will not share its data because they are all creating a little wall. They all talk of universal ideas and values to humanities, but they are all creating their own little territories and this. So when they talk about inclusion, they are saying inclusion of what? Because they will not include other people's data, they won't share their data. So there is not real inclusion, right? So and that's what is an interesting thing. You see in India only one or two business houses are favoured over others because it is easier to work with one or two people rather than with people from all states, all people. So diversity is we are told that for India to be successful we have to be homogeneous. One business house, one way of thinking, one Delhi controlling everything. So it sounds very efficient, right? One God and this idea of one is very monotheistic. It's not an Indian way of looking.

How do you find these lessons in the Gita, in Ramayan, in Mahabharat? How do you sort of make these linkages? Maybe you can tell us a story that, you know, sort of illustrates this idea of diversity.

We have heard of a God called Vishnu. And Vishnu, we are told, is the preserver of the world. But how does he preserve the world? Depending on the context, he manifests in a different form. So he takes the form of Ram in Tretaya Yug. He takes the form of Krishna in Dwaparayug. So even God takes many forms to establish Dharma which means there is no one way in which you can live. Now, Ram comes from a royal family, comes from a privileged elite background. Krishna is from a cowherd community. So it's not the same thing as being born as a royal Prince, the eldest son of the royal family. And, therefore, you see the idea that one God has to manifest differently in different situations, historical situation.

So you have the idea of Vishnu as one who preserves the world, and wherever Vishnu goes, we are told Lakshmi follows. Lakshmi is the goddess of wealth and fortune. But Vishnu always manifests on earth in different forms, and these are the avatars. So he becomes a Ram in the Tretayug, he becomes Krishna in the Dwaparayug. Ram follows rules. Krishna breaks rules. Ram is from a royal family. Krishna is from a cowherd family. Thus God has to take many forms to establish Dharma. So it's not standardized. So some people will worship Ram, some people will worship Krishna, some people will say I will worship Vishnu. But Vishnu does not make sense unless you understand Shiva. And therefore you suddenly see even the gods are having different forms, different temples. Across India, there are different temples, there are different practices, different rituals. People are trying to standardize the temple practices, right? They are trying to standardize just as businesses try to standardize; they say that every market has to behave exactly the same way. When we want everybody to think in the same way. We want consumer economy to function in that way. It is basically we don't want to be Vishnu and when you don't want to be Vishnu, you will never attract Lakshmi. So this obsession with what you know, standardization and uniformity, which informs Western business practices and is now slowly percolating into Indian business practices is interesting. It's not going to work but well we can try.

You've talked about regulation as being akin to parenting, and thats how the nonviolent regulation sort of happens. Can you unpack that a little bit?

See there are two types of regulation this violent regulation and there is non violent regulation. What is violent regulation? Where the regulator is basically a henchmen who ensures you get your booty right and that is violent regulation. So all empires had it, the Holy Roman Empire had it, the Caliphate had it. You always have these henchmen managing the show ensuring that the king gets his booty.

Now non-violenct regulation is self management where you at a certain stage of life and remember the varna system and the ashram system in India where at a certain stage in life you give up. You know you the first part of your life, you make a lot of money, you become successful, you prove that you are capable of managing the show. But in the second part of your life you let go of everything. That is where your spiritual growth happens and then you become worthy of being an elder and a regulator for the next generation, which is not talked about nowadays, right?

Nowadays we want to be CEO till the day I die. And that is not what they are talking about. The CEO has to give up everything. He cannot enjoy the profits that he has earned. He has to become Digambara. And of course Digambara is a high idea, but you have to walk the path of the Digambara. Digambara means the one who has given up everything. You know it is good luck, gives up everything and he walks the path of the Digambara, lets go of everything and enables others because he is now got the knowledge with him. He passes on his knowledge with the next generation, so he gives up his wealth, he gives up his knowledge, he gives up his power, maybe his gender. Everything I am saying is speculation, but at least it makes us think differently. Because we now live in a world which seems to celebrate the Bakasur: Eat more, make more money, make more money without consequence, and that is a dangerous thing. And I would like to believe that Harappan civilization was not as violent civilization and you know, it really collapsed because the Sumerian civilization collapsed. Its trading partner was no longer (around), the demand supply gap shifted, but the cities collapse. The villages continued, the trade continued, but the cities collapse. But really the civilization does not collapse because we confuse cities with civilization. People still thrived, agriculture rose, livestock rose. So regulation came because somebody wanted to make money.

Now in a violent regulatory system only the king makes his booty and basically he is enslaved his people, which is what you find in ancient Egypt. But a non-violent ecosystem is saying that I have to regulate myself and only when I regulate myself can I regulate others. If a regulator does not regulate themselves, how can they regulate society? So spirituality and this whole idea of looking within I think was very essential to Harappa. That is why the old Jain model, not the new Jain models, the Jain models today don't talk about all these things, but some of the best ideas in business come from Jainism and Buddhism to a degree. I think Jainism is far more refined. Buddhism has ideas, but because the Buddhist monks were allowed to own property while Jain monks would not own property - this is a big foundational difference between Buddhism, Buddhist monks and Jain monks. I think this sort of makes you think differently, negotiate differently, manage conflict differently, and I think you have forgotten these ideas. And I try very hard in my books to make people aware of these ideas because they are very spellbound by the East India Company discourse. We only sort of wrap it in Indian clothes, but we are still following the East India discourse where we think regulation applies to others and not to yourself. That's how the East India Company functioned when they were plundering India, right? And that's how I think many regulators do.

Illustrations by Devdutt Pattanaik in 'Ahimsa: 100 Reflections on the Harappan Civilization' (2024).

Illustrations by Devdutt Pattanaik in 'Ahimsa: 100 Reflections on the Harappan Civilization' (2024).

Tell us why you draw. Do you think visually? It's an interesting contrast to have the words on the page and then have illustrations with little arrows to explain what they signify. Tell us how you approach the illustrations in your books.

I was a student of science, of medicine, and I realized that when you draw diagrams, you explain things better in physics, in chemistry, in biology. Then when you go to the corporate world, you see that when you do a PowerPoint presentation, good PowerPoint presentations have more images and less text. And I realized that that's how you communicate. I am interested in communicating. I don't want to be an author or an illustrator. I want to communicate ideas of mythology and how it can be applied to day-to-day life. That's my goal. I use writing but I found that to be insufficient. Therefore, illustrations become important, maps become important, tables become important, bullet points become important. They are all tools to help the reader understand complex subjects.

The illustrations you will see they are like very simple line diagrams, capturing only the essence. There is very little shading; I don't try to make it pretty, I try to make it accessible. That's why I don't use colour, I only use black and white. They are easy to produce. It takes about 10-15 minutes to do one illustration, and I mass-produce them like a factory. Because I want young people to get excited about Harappa and Rakhigarhi and Kalibangan and Lothal and the fluvial (river) trade, coastal trade, logistics. I want Indians to understand economics better, make money - not for themselves, but for people around them, because that's the Sanatan way...

The real Sanatan is where you make money for others, not for the self, and not the East India Company (way of) making money, but the Harappan way of making money, enabling, giving it to helping every ecosystem around you become Vaikunth. I think that's what I try to do in my work. Therefore mythology, writing, illustrations - all move towards the business space.

I am not interested in western models at all which are going to destroy the world and society. I am interested in Indian models, and I find them in Jainism, Buddhism, in Vishnu-Shiva traditions. I find that beautiful; the idea of Lakshmi coming into your home.

What do you expect or hope readers will take away from this book?

Understand how economics is related to spirituality. In Hinduism, Goddess Lakshmi is the auspicious goddess. And Mangalya is something that we all seek. We all want success in life. But Mangal, there is Labh and this Shubh Labh. Labh is profit, the East India Company model of making money, which is followed by most businessmen and most nation states. And then there is Shubh Labh - the traditional Indian way of making money which makes you rich, but then one day you realize wealth is not everything, wisdom is greater than wealth and you help others. As I said, you self-regulate in order to regulate the others. And I think that way of thinking is the takeaway.

This time, instead of talking about Ramayana and Mahabharat, Shiva, Vishnu, Harah, Hari, Lakshmi, Durga, I am talking about something totally different, but as I discovered, quintessentially Indian: the Harappan civilization and the cities of Rakhigarhi, the cities of Lothal, Dholavira and the trading practices which are very closely linked with spiritual traditions and mythology, which is what I want people to understand that Lakshmi is sacred even 4,500 years ago.

So a lot of the stories our forefathers told us about how to live and how to do business, you find that those can be relevant even today?

Yes, otherwise what have we achieved? We have got communism which is basically envious of rich people, and we have capitalism, which has a disdain for poor people. These are terrible western models, and we seem to be trapped between capitalism and communism... never look(ing) towards the Indian models... the beauty of Jainism... the beauty of Hinduism. Indra and Vishnu talk about wealth in very, very different ways. I think we are proud Hindus who don't read Hinduism...

I want people to see the Indian model of business which is based on yagya. I have written about it in my book 'Business Sutra'. I have written a lot in on leader culture. I have written a lot about it, but somehow people think of it as exotic.

But let's not forget that communism and capitalism are based on violence. They have caused global warming, climate change, social inequality and now young people are dying because they have been told to work hard and have inner strength, and we are celebrating this exploitation. This is exactly the East India Company model of making money and that is not healthy at all.

So, you need new ideas. Where are you going to get them? Not in capitalism, not in communism, not in the history of the East India Company or the plundering narratives of corporates, but a new way of thinking. Let's look at Jainism. Let's look at Buddhism. Let's look at Vaikuntha. Let's understand why is Vaikuntha different from Swarga. Let's look at the Harappan model.

Let's find new ways of looking at business. We should stop using the word ambition, which is really a code for greed. Just stop it. We are like children continuously obsessed with wealth and not enabling others to make wealth because enough is never enough because that's the capitalist way. The communist way is always revolting. These are foolish old ideas which have not worked in the last 100 years.

I think we need new ideas. And a great place to begin (looking for them) is India, and a great place to start is Devdutt Pattanaik's books. So read my books, think differently and have the courage to say Bakasur is not the right way to be (laughs).

Speaking of your books, what are you working on next?

I am actually working on Bakasura. Honestly!

I am writing a slightly more philosophical book about: Can we think differently about money and wealth? (About how) Lakshmi is joyful, wonderful, brilliant. And what is the difference between Labh and Shubh? Labh, I have written little bits about it, but I have noticed that the richest people in the country are extremely insecure and as long as they are insecure, they will never get out of the Bakasur trap.

So it's in the 21st century tradition of books about why capitalism has failed us?

And communism (has failed us). When you give only one side of the story, that is not the Indian way. Indian way has to look at both sides of the story. Because you see our linear thinking will always say capitalism failed us, oh then communism is better, socialism is better... both failed. I mean they are completely self-serving. This is a problem with the West.

You have to be, perhaps, a capitalist in the first part of your life and a communist in the second part of your life. In the early part of your life, you have ambition, you make money, you do grihasta ashram, you become a zillionaire, you become the Unicorn or whatever you want to be. But in the second part of your life, instead of being the predator, can you be the prey? Can you allow yourself to be consumed by others? Will you do that? Because that's what happens in nature. Will you be generous? Will you enable (others)?

People use words like I am a mentor. What does mentor mean? Unless you have the skin in the game, you allow yourself to be consumed, you take risks with the next generation, you allow the next generation to make mistakes and think differently and not just like you. Then I think something wonderful will happen. Because if you don't change, they won't change. If you just want to stay capitalist all your life till the day you die, then it's such a tragic life.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.