On July 13, the State Bank of India (SBI) issued a new series of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bonds. The issue was widely viewed as having performed poorly – the bank raised just about a third of what it had set out to do, despite offering a premium of 100 basis points over the interest rates on government securities (G-Secs). This has reportedly spooked several PSU banks that were planning to issue such bonds, compelling them to have second thoughts.

The subpar performance of SBI’s July bond issuance is puzzling because the bank had raised around Rs 3,700 crore through a similar issue at a premium of 66 basis points over the interest rate on G-Secs in the previous quarter. That issue was oversubscribed over two times, suggesting strong investor interest in such bonds as recently as March 2023. In the Rs 10,000 crore July issuance, the bank managed to raise only about 30 percent of the amount. The large size of SBI’s July issue and its long tenure are popularly believed to be responsible for its underperformance. We offer an alternative explanation for this outcome.

In 2020, a Reserve Bank of India (RBI) appointed administrator in Yes Bank’s restructuring process unilaterally decided to wipe out the holders of the AT1 bonds issued in 2016 and 2017 by the beleaguered bank, without writing down its equity shareholders. The administrator’s decision to prefer Yes Bank’s equity shareholders over its bondholders triggered a chain of reactions from the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) on the one hand and the courts on the other, which explain a general aversion towards AT1 bonds. To the extent that this aversion raises the cost of keeping Indian banks well-capitalised, this has fiscal implications for the government of India, the single largest shareholder of Indian public sector banks. More importantly, this aversion underscores the urgency with which the Supreme Court must decide the challenge to Yes Bank’s bond write-off, scheduled to come up for hearing on August 21.

Appetite for bonds

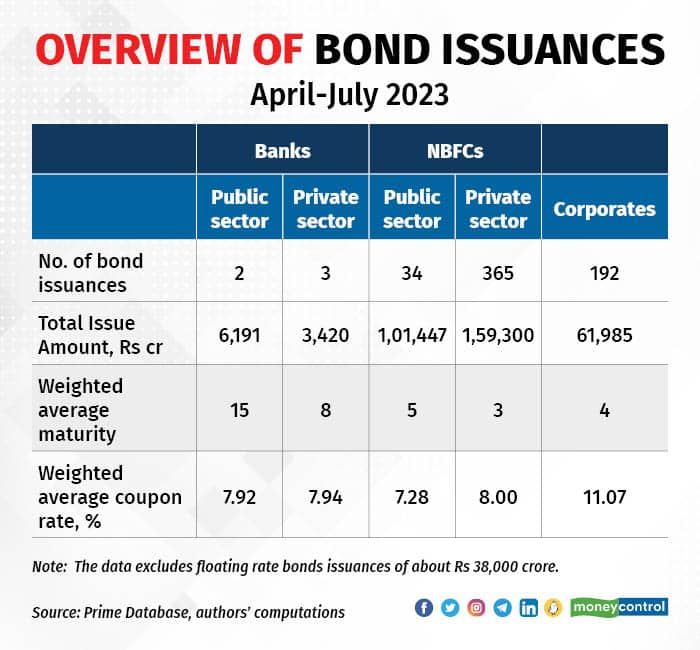

The success of any bond issue depends on a variety of factors — domestic and global macro-economic conditions, the financial health of the issuer, terms of the issue and investor appetite, and many of these are endogenous to one other. While it is hard to pin down a causal explanation for the underperformance of a bond issuance, an overview of the issuances in the current fiscal suggests that there is an appetite for the bonds of both PSU and non-PSU banks.

The above table dilutes the force of some of the reasons, such as large issue size and longer tenure, that were offered in the press to explain the bond issue’s poor performance. Public and private sector banks have made issues that are comparable to the SBI’s issue in size and maturity in the previous quarter, suggesting that there seems to be a prima facie appetite for large issue sizes with long maturity periods. Also, to be noted is the overall buoyancy in the bond market — over Rs 3.50 lakh crore worth of fresh bonds issued in the first four months of the year.

Regulatory Action Impact

AT1 bonds are contingent convertible bonds, which, unlike vanilla bonds, can be written down or converted into equity shares of the issuer, on the occurrence of pre-defined contingencies, generally linked to the issuer’s financial health. The decision to write off Yes Bank’s AT1 bonds in 2020 prompted SEBI to take several steps to protect investors from the risks inherent in such bonds.

A key step was capping the exposure that mutual funds could take to AT1 bonds and mandating that the bonds be valued by mutual funds at an effective maturity of 100 years. While all the AT1 bonds are ‘perpetual’ bonds de jure, they come with a call option at five years maturity. Banks have exercised this option in all such bonds issued so far, thus making them bonds of five years maturity, de facto. Valuing these bonds at a maturity of 100 years suppresses their valuations, making them unattractive for asset managers. This valuation rule kicked in from April 2023, providing one possible explanation for the undersubscription of SBI’s AT1 bond issuance of July.

Another step taken by SEBI was to restrict retail investors’ access to such bonds, by measures such as raising the minimum allotment value and minimum lot size for secondary trading in these bonds to Rs 1 crore. At about the same time, amidst an outcry over these bonds having been missold to investors, SEBI penalised Yes Bank and its private wealth management team for having sold such bonds to individual investors. These regulatory actions triggered by the AT1 bond write-off are likely to have affected both investor interest and the general distribution chain for selling such bonds.

Uncertainty Generated By Courts

The aversion created by the regulatory restrictions is amplified by the uncertainty created by courts in dealing with the challenge to the write-off. In 2021, some AT1 bondholders challenged the decision of Yes Bank’s administrator to force them to absorb the losses suffered by the bank before equity holders. While the Bombay High Court set aside the administrator’s decision at the beginning of this year, the victory was precariously perched on technicalities and short-lived. In this article, we had critiqued the High Court judgement for not questioning the fairness of the administrator’s decision which upended a cardinal principle of corporate finance of equity shareholders as the first loss absorbers without offering any reasons for doing so. A reasoned determination of this question was critical to the case at hand and for Indian banking generally. The RBI challenged the Bombay High Court’s decision in the Supreme Court and the matter is now awaiting a substantive hearing on merits.

A similar write-off was done in March 2023 by the Swiss National Bank (SNB) in Credit Suisse’s rescue plan, giving this issue a global dimension. The SNB’s decision triggered statements by the ECB and the Bank of England reassuring the public that they would not resort to such write off in restructuring banks in their own jurisdictions. We believe that this would have implications on the way the Indian Supreme Court would look at the decision of Yes Bank’s administrator, if it does decide to look into the merits of the decision.

The underwhelming performance of SBI’s AT1 bond issue is perhaps indicative of the new normal for subordinated bonds issued by banks and financial institutions. Banks may have to significantly increase the premium offered on these bonds, given the uncertainties associated with the loss absorption hierarchies. Meanwhile, it is imperative that the Supreme Court decide the legal challenge on the AT1 bond write-off on merits. Investors need to know what they are buying, and regulators need to know whether their discretion in bank restructuring exercises is unbound or bound by the need to explain extraordinary decisions that reverse the fundamental tenets of corporate finance.

Bhargavi Zaveri Shah is a doctoral student in law at the National University of Singapore. Harsh Vardhan is a management consultant and researcher based in Mumbai. He serves as an independent director on the board of Karur Vysya Bank. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.