Henry Kissinger called it “the economic equivalent of the Sputnik challenge.” Exactly 50 years ago today, the US found itself under economic assault after Arab nations weaponised oil, starting a petroleum embargo that brought the global economy to its knees.

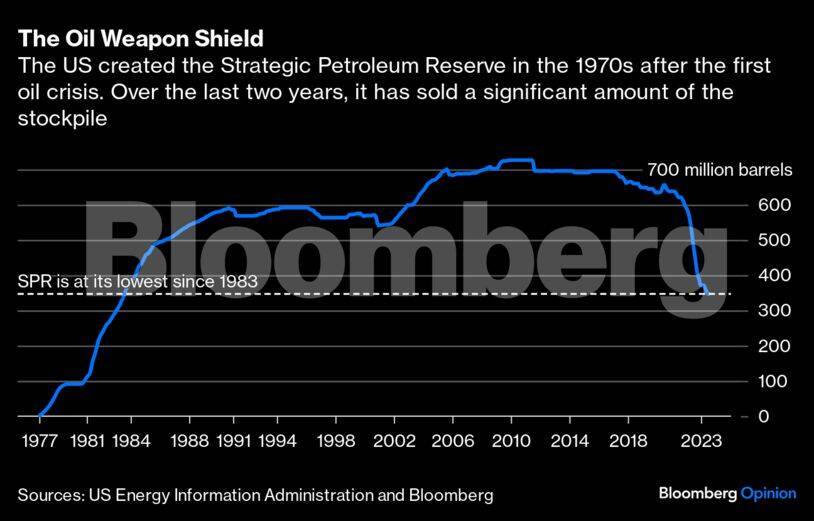

Kissinger, vowing America would never be blackmailed again, designed a shield against the oil weapon: the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. A stockpile containing hundreds of millions of barrels of crude, its function was to offset the impact of any future supply disruption, intentional or not. Half a century later, Washington has forgotten that lesson.

The SPR today contains less than half the crude it had at its peak just over a decade ago. At about 350 million barrels, it's at its lowest since 1983. To put what’s left into perspective, the US released about 270 million barrels over the last two years to cap oil prices. If the SPR is a revolver, it has a final round left in the chamber — and that’s it.

The ignorance could not come at a worst time. Despite the differences, the parallels between Octobers 2023 and 1973 are easy to draw. The risk of an Arab oil embargo is close to zero, but there’s a growing danger that oil supplies could be disrupted should the conflict spill over beyond Israel and Gaza, ensnaring Iran.

True, the US currently pumps enough crude and other oil liquids to satisfy domestic consumption, a key difference with the 1970s. Yet it’s equally exposed to global oil-price fluctuations. In the oil market, a disruption anywhere is a disruption everywhere. Energy independence is a nice political slogan — and an economic lie.

The SPR fulfils two roles. First, it deters hostile nations from threatening to use oil as a weapon; second, it’s a backstop if global supplies are curtailed. To accomplish both, it requires enough barrels. I don’t think what’s left today is enough. Many blame President Joe Biden for the shortfall, but the truth is that both US parties have played politics with the reserve. Congress has used the SPR as an ATM, selling barrels to raise cash to cover unrelated shortfalls in the American budget.

How large should the reserve be? There’s no magic number, but everyone seems to agree that the appropriate level is more than what’s set aside today. Naysayers may argue that US demand will ultimately fall as more drivers buy electric vehicles. They’ll eventually be proven correct — but not for the next decade, or even longer. A shield is therefore still needed. After talking to multiple current and former officials, including those who played a key role creating the reserve in the 1970s, something around 500 million barrels — or 40 percent more than today — sounds about right.

The Biden administration has promised to refill it, but perhaps not before 2025 — by which time its fate depends upon the outcome of next year’s presidential election. “The bottom line is we are going to replenish,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in July. So far, the administration, which has an eye on gasoline prices and their likely influence on voters, has bought back only a pittance.

Originally, the government promised to refill the SPR if oil dropped toward the low $70s-a-barrel level. But when prices fell in May, June and July, it bought only a few million barrels, procrastinating over a key national security issue. Ironically, money isn’t the most immediate problem.

Proceeds from previous sales, plus appropriations from Congress, pay for purchases. The 180 million barrels sold last year generated $17.2 billion, of which $12.5 billion was diverted to cancel several future SPR sales Congress had mandated for 2024 to 2028. That left $4.7 billion to replenish the reserve. So far, the Biden administration has used $450 million to buy just over six million barrels. The remaining $4.2 billion would buy about 50 million barrels extra.

The White House should pay attention to the energy market, but it shouldn’t treat the SPR like a hedge fund. Whether or not last year’s actions were a great trade, the US government isn’t in the business of buying low and selling high; its role is to buy insurance.

To lift the SPR to the 500 million barrels I see as optimal would require extra money from Congress. At current prices, buying 100 million barrels would cost $8.7 billion. That sounds like a lot — but it’s dwarfed by the more than $13 billion spent on the new aircraft carrier Gerald Ford, the vessel the administration has dispatched to the eastern Mediterranean.

Still, as someone once said, a billion here and a billion there and pretty soon you’re talking about real money. It needs to come from somewhere. Ultimately, that means higher taxes. I know that gasoline levies are the third rail of US politics. Still, that’s what’s needed. Washington hasn’t raised its federal gasoline taxes since 1993, under Democratic President Bill Clinton. It should increase them now to pay for a bigger SPR.

America consumes about 8.9 million barrels a day of gasoline, equal to some 375 million gallons. The federal tax has been fixed at 18.4 cents a gallon for 30 years, losing half of its value since then because it’s not indexed for inflation. Lifting the federal tax by exactly half the 5-cent increase approved by Republican President George HW Bush in 1990 would raise about $9.5 million a day, or about $3.4 billion a year. In less than three years, the US would have raised enough money to pay for refilling the SPR.

The policy would be a win-win-win: it would buy insurance against hostile nations, support the US domestic industry by buying crude from them and help fight the climate crisis by raising the cost of gasoline, denting demand. If not now, when?

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.Credit: BloombergDiscover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.