Birthdays are in equal parts celebratory but also inherently tinged with regret, for opportunities missed and mistakes made. All of which may well be weighing on Beijing as its Belt and Road Initiative marks its 10th anniversary this year. For the most part, it has been a success, coinciding with a coming of age for China’s financial and political importance on the global stage. But the next 10 years are unlikely to be as prosperous or smooth. The external geopolitical environment, combined with the nation’s domestic challenges, will make the BRI, as it is known, far less prominent than it has been.

Called the “project of the century” and “China’s Marshall Plan, but bolder,” the BRI’s vision was articulated during a speech in Kazakhstan in 2013 by President Xi Jinping. He evoked a golden era of trade and friendship between the Chinese and the rest of Central Asia, proclaiming that “a near neighbor is better than a distant relative.”

Xi repeated that sentiment in a follow-up speech in Jakarta later that year, reminding people of when Beijing had stepped up to assist in the aftermath of the Aceh tsunami in 2004. Highlighting China’s new age of benevolence and generosity, Xi’s pitch was to convince emerging Asian giants like Indonesia that siding with China made economic sense. The strategy paid off: to date 147 countries, worth about 40 percent of global GDP, have signed on to BRI projects or expressed interest in them.

Indonesia is one. This week, Jakarta announced the completion of its China-backed project — the Whoosh bullet train that will connect the capital to Bandung in West Java, reducing travel time from three hours to about 40 minutes. On paper, this is the ideal BRI project, but it has already been mired in delays and rising costs — highlighting the issues when Beijing’s money is attached to a deal.

To understand why China’s infrastructure program attracts controversy, it is worth understanding how it started: As a way to save its own economy during the tumultuous aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. The government put in place a multi-billion-dollar stimulus package and launched a massive infrastructure program, leading to a saturation of the market in the process. The BRI was seen as a solution to this “issue of excess capacity,” as the Council of Foreign Relations notes, and led to an “explosion in the number and location of new overseas foreign contracted projects signed by Chinese companies.”

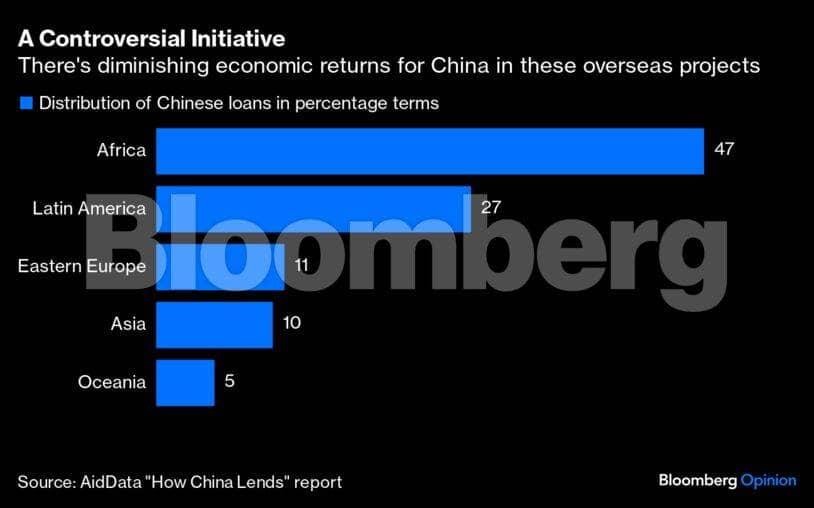

Africa, Asia and Latin America were among the biggest and primary destinations for these government loans, according to analysis by AidData, a research lab at the US-based William and Mary’s Global Research Institute. It was a marriage of transactions: These countries needed the funds and expertise Chinese companies could disburse, and Beijing needed a way to extend its economic and political influence overseas.

Very quickly, though, China’s largesse was deemed a debt trap — in particular by the US. Although this branding is not entirely fair, many of the projects Beijing had signed began to raise suspicion, particularly in South Asia, where countries like Sri Lanka and Pakistan had taken on huge debts and were struggling to pay them back. In return, strategic ports were either leased to, or developed in conjunction, with China, leading countries like India and the US to claim the goal all along was nefarious — a geo-strategic expansion plan backed by funding from the state.

AidData’s study points to strict contracts between Beijing and foreign governments, requiring the right to demand repayment at any time — suggesting that this could be used as leverage over countries to toe China’s line on political issues like Taiwan, for example.

That suspicion will thwart the long-term goals of the BRI, while China is also facing higher levels of competition for such projects from the US and its allies, who are offering alternative programs, albeit on a much smaller scale. Then there’s the actual commercial viability of these projects that a slowing China may think twice about as it tries to shore up its domestic economy. “There are fewer of those lower-hanging fruits, the big infrastructure projects that Chinese companies would lend money to and help build,” Jamus Lim, associate professor of economics at ESSEC Business School, Asia Pacific, told me. “There are diminishing economic returns from investing in projects overseas for the Chinese — and on the geopolitical side, the possibility of new governments coming in across Asia with regime changes in store, it is also harder to predict whether countries will be as welcoming to Chinese money in the future.”

Some of that skepticism is already evident. In the case of Indonesia’s bullet train, it isn’t clear when it will return a profit. And Jakarta is increasingly pushing back against Beijing, insisting that China Railway transfer its technology to Indonesia so it can produce the trains domestically. Meanwhile, Italy has considered abandoning the program.

Don’t expect any of this negative sentiment to overshadow the 10-year celebrations when Xi addresses his dignitaries and guests later this month. Instead, there will be the necessary congratulatory cheering over cake, cocktails and champagne. No matter how grand the event, it will be hard to ignore that Chinese funds for overseas investment have been drying up since 2018, and the focus on big infrastructure projects is unlikely to return. Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative era is by no means over, but it will have to find new ways to thrive.

Karishma Vaswani is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.Credit: BloombergDiscover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.