One of the biggest complaints from Budget 2022 has been the absence of any breaks—tax or otherwise—for the common Indian. When asked about this in the post-budget press conference on February 1, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman even apologised, saying "there are times when tax can be cut and there are times when the public will have to wait".

But who truly needs a break from the government?

According to the National Statistical Office's first revised estimate for FY21, India's per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was Rs 1,46,087 in nominal terms, down 2.4 percent from FY20. When measured in real terms, the per capita GDP was a mere Rs 1,00,032, down 7.6 percent from FY20.

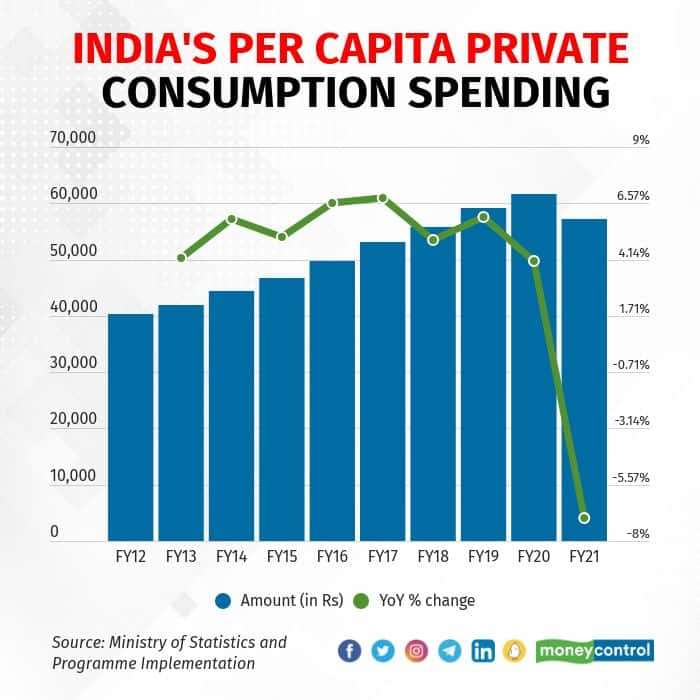

But it is perhaps more instructive to look at the average Indian's spending power. The real per capita private final consumption expenditure fell 7 percent in FY21 to Rs 57,279. This amounts to less than Rs 5,000 per month of private consumption expenditure per person.

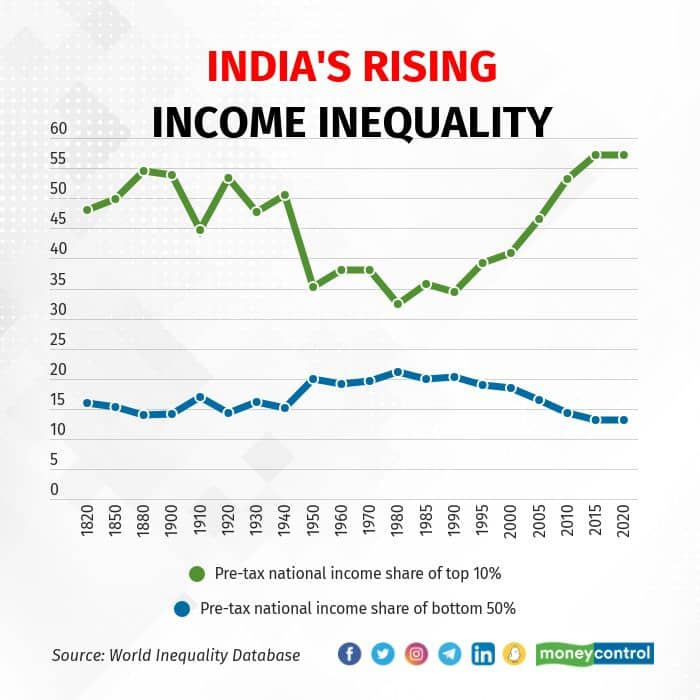

That inequality is high in India is not news. According to the recently updated World Inequality Database, India's current income inequality levels are the highest in 200 years, with the top 10 percent of Indians having a 57.1 percent share in the pre-tax national income in 2020. Meanwhile, the bottom 50 percent accounted for just 13.1 percent of the pre-tax national income.

Despite these inequalities, private final consumption expenditure is expected to grow 6.9 percent in FY22. Who is responsible for this growth? Cue the K-shaped economic recovery hypothesis and India's famed middle class. Or perhaps even the "new middle class".

The Harun India Wealth Report 2020 defined the Indian middle-class household as one with annual earnings of more than Rs 2.5 lakh and a net worth of a maximum of Rs 7 crore. It estimated that 5.64 crore families fell in this category. However, the report also mentioned a category it called the "new middle class". These households, estimated to number around 6.33 lakh, have a minimum annual earning of Rs 50 lakh and a net worth of at least Rs 7 crore.

So just who really requires the government's support? The new middle class, undeniably, does not. Those in the upper echelons of Harun's middle-class category don't either.

Those who do, however they may be defined, have plenty of reason to complain. For instance, five key items—food and fertiliser subsidy and allocations for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, PM-Kisan, and midday school meals—have seen their allocation for FY23 nearly halved from what was spent in FY21. Compared to the revised estimate for FY22, the allocation for these five items is down by a quarter.

Yes, the budget did not provide any tax breaks or other sops to the middle class. And yes, the middle class and the classes above it are responsible for much of India's consumption and growth. But amid all the capex brouhaha, the pursuit of growth, and the benefits that may accrue in the medium to long term, a class of Indians could fall dangerously behind in these worst of times.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.