Ajay Kumar (name changed) drives the ubiquitous kaali-peeli in India's financial capital, Mumbai. He says all he wants is cheaper food and fuel – a demand being heard everywhere ahead of the 2023-24 budget.

"Sirf do cheez chahiye: khud ke liye khana-peena, aur apni gaadi ke liye gas. Woh bas sasta ho jaye," is how Ajay Kumar phrases his wish list in Hindi.

Set to be presented in Parliament on February 1 by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, the Budget for 2023-24 is being preceded by the usual calls for easing the burden on low-income groups and the middle class. People are feeling the pain particularly badly after several years of high inflation.

Admittedly, headline retail inflation has eased sharply in the last few months, with the latest print for December at a one-year low of 5.72 percent. Food inflation also slumped to a one-year low of 4.19 percent last month.

Even so, Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has been above the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI) medium-term target of 4 percent for 39 consecutive months.

Fuel and food prices

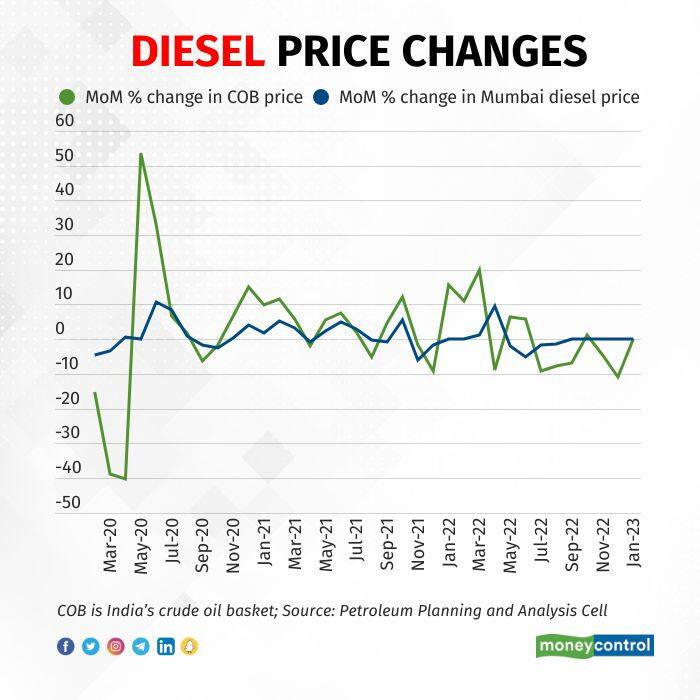

Ajay' livelihood depends on the taxi he drives. And domestic fuel prices have not moved in tandem with the price India pays for its crude imports.

While diesel prices did not increase month-on-month in the first half of 2020 as sharply as the price of India's crude oil basket, they have barely moved in the last half year or so.

The price of India's crude oil basket is down nearly 33 percent since June 2022. On the other hand, the price of diesel has fallen by only 3 percent. As such, the budget is being keenly watched for some relief the on the fuel front.

Like fuel, food prices have been increasing too, forcing the government to take several measures last year to keep a check on prices of staples such as cereals, edible oils, and pulses.

In 2022, food inflation, as measured by the CPI, averaged 6.8 percent, more than double the 3.1 percent it averaged in 2021.

Consider the case of the 68-year-old Kayani Bakery, known for its insistence on operating out of a single branch in the heart of Pune, and its wildly popular Shrewsbury biscuits, which now sell for Rs 600 per kg, up 50 percent in five years.

"Butter prices have increased. The shop had to be closed for 2-3 months early in the pandemic. They don't have an option but to increase the price of the biscuit," says the owner of a local kirana store at the opposite end of Pune, who buys the famed biscuits from Kayani and sells it to his neighbourhood customers with a mark-up of Rs 20 per half kg.

Inflation for milk products has averaged more than 8 percent since the middle of 2021.

More in the pocket

Any budget talk is incomplete without a demand for tax benefits.

The Centre introduced a new, voluntary income tax regime with lower tax rates in the budget for 2020-21. However, the downside of this optional regime is that it did away with exemptions and deductions available under the old system.

According to the government, the new, optional regime can lead to lower tax payments for certain individuals.

Going by Sitharaman's recent comments in an interview, the middle-class can expect little on the income tax front.

"I can understand the pressures of middle class. I identify myself with the middle class, so I know. But I also want to show the government's work in this area: no new tax has been levied on the middle class," the finance minister said on January 15.

Sitharaman went on to list the actions taken by the government to make the lives of the middle class easier: not taxing those with an annual salary of up to Rs 5 lakh, the introduction of metro trains in 27 cities to help commute, supply of drinking water to more than 111 lakh homes, and money to make 100 cities smart, among others.

"I haven't put money in the pocket of every middle class person, but all these facilities (are for the middle class). Yes, we can do more for the middle class. The size of India's middle class is becoming big. I quite recognise the problem. I am not saying that we have done all this and that's it. We are doing things to help the middle class and will continue to do more things," she added.

If the working-age middle class can expect little, others still have their hopes up.

"There needs to be something for senior citizens," says septuagenarian Rahul Singh (name changed), a retired doctor.

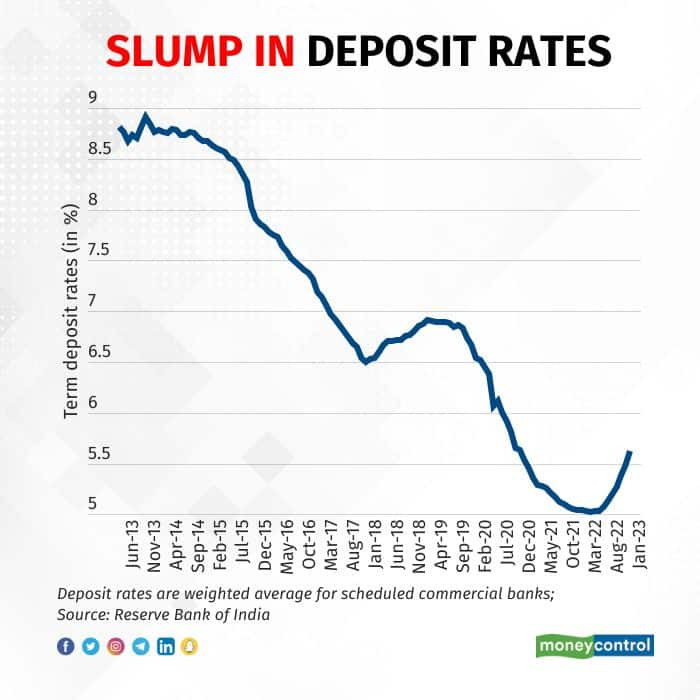

"Interest rates have been low over the last few years. If you are living on interest income, it is a big issue," Singh added.

The pandemic saw a big fall in interest rates as the RBI infused historic levels of liquidity to support the financial system. While that helped lower lending rates, it also led to lower interest rates on deposits – a key source of income for the retired.

According to data from the RBI, the weighted average interest rate on banks' term deposits had dropped to nearly 5 percent for much of the second half of 2021-22. For example, if a five-year, tax-saving fixed deposit carried an interest rate of 8.25 percent in late 2018, the same bank is now offering the same deposit at an interest rate of 7 percent.

The RBI's rate hikes since May 2022 have since led to an increase in deposit rates. But at a time of high inflation, the real rate of interest on these deposits will be close to zero, if not negative.

All in all, the Indian consumer has had it tough these last few years. And given that the revival of demand is crucial for private investment cycle to move up and boost growth, measures to help ease the price burden and boost disposable incomes can be beneficial for the individual as well as the economy in general.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.