Lipika Singh Darai met the maverick Indian New Wave filmmaker Mani Kaul at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, when he was taking a workshop for the direction students. She was not in his class. But he happened to watch her design her diploma in the 5.1 sound studio. A fascinated Kaul later heard her singing and asked her to record an in-house singing session. Through music, and food, their friendship started. Kaul, whose films are known for sound design, then, asked her to design the sound for his feature film, which was supposed to be produced by Anurag Kashyap, Darai had heard at the time. It was a huge responsibility for the fresh film-school graduate. She was both excited and nervous. The preparatory mode entailed long discussions over phone and a few sessions of ambience recordings. “He [Mani Kaul] was the first one to tell me: even if your music teacher is no more, just go for what you are looking for. That’s how the first film (the short A Tree a Man a Sea, 2012, on her music teacher) took place, but he was no more to watch it. He would have been really happy to see me how I have evolved as a person,” says Bhubaneswar-based Darai, 40, who was trained in Hindustani classical music for seven years by the late Prafulla Kumar Das. The inability to pursue vocals/singing professionally made her take up sound recording, so that she could at least be around musicians. That led her to FTII.

When Darai was asked during her FTII entrance what sound she likes the most? The sound of rain was her prompt response. She’d graduate from FTII in 2010, specialising in sound recording and designing, which was then called the Audiography course. She was the only woman student in her sound batch of 10 students.

In 2010, she won her first National Award, for Best Audiography (Non-Feature Film), for her then senior (now Marathi filmmaker) Umesh Vinayak Kulkarni’s Hindi/Marathi short film Gaarud (2008), which had premiered at 2010 IFFR’s Tiger Awards Short Film Competition. Over the years, Darai has transitioned from being a sound recordist to an indie filmmaker and editor in her own right. Darai would go on to win three more National Awards: Silver Lotus Award for Best Debut of a Director (A Tree a Man a Sea, 2013); Best Non-Feature Film Best Narration / Voice-Over (Kankee O Saapo, 2014); and Best Educational Film Award (The Waterfall, 2017).

Darai, who belongs to the indigenous Ho community of Odisha, returned to the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) for the second time as a filmmaker after Night and Fear in 2023, the second film in her series of personal essays or letters or the filmmaker’s imaginary conversations with her late grand aunt, that began with Kankee O Saapo (Dragonfly and Snake, 2014). This week, she premiered the final film in the unintentional trilogy, B and S, at the Short and Mid-length segment of the festival. This short film has been produced by Delhi-based Rough Edges (founded by Ridhima Mehra and Tulika Srivastava, who previously ran the show at the Public Service Broadcasting Trust or PSBT). Darai’s B and S works as a double bill, a companion piece to Ektara Collective’s Ek Jagah Apni (A Place of Our Own, 2022), in which, too, two trans friends struggle to look for a home in a transphobic city. However, the epistolary film, B and S, is not about the friends’ struggle with their trans identity. It is an imaginary conversation of the filmmaker with her grand aunt, where she tells the story of B (Biraja) and S (Saisha), who appear, sharing their memories, negotiating the meaning of transness, love, loss, friendship, building a home together as friends, and violence. A teak tree and a little parrot help Darai intertwine these narratives.

Edited excerpts from an interview:

You return to IFFR after two years. What does the festival mean to you?

The festival has nurtured me. It focuses more on what it stands for, to build a thriving ever evolving art community and support independent voices across the globe. Along with the screenings, they have many talk and mentorship sessions. At one such mentoring sessions, Hayet Benkara motivated me immensely the last time around. She was proud of my body of work and advised some pertinent things at the right time when I was hesitant to take a few steps in terms of filmmaking and life. Then, I tried to take some conscious steps to connect to the wider filmmaking community by applying for Hubert Bals Fund (HBF), BAFTA Breakthrough and so on…

In what way being a BAFTA Breakthrough India 2023 participant help?

Because of BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts; its Breakthrough India programme celebrates new-age talents), some people came to know about me in the UK, and someone reached out to me who approached me and did the initial music sketches for Birdwoman, which will be my first feature fiction film (in Odia language).

Four National Awards — how important are awards to you?

Personally, I don’t chase or desire awards or recognition. I often run away from these things. If you put me on a platform and a number of people are watching me for a felicitation or award, I get very anxious. However, especially the National Film Awards have helped me position myself as a filmmaker in the eyes of the audience or those who watch or read about my work. They’ve added to my profile, which helps funding bodies or those who hire me to have more confidence in my work. Because of my debut director award, people in Odisha began to know about my work and started referring to me as a filmmaker. My [Adivasi] Ho community identity also came to the foreground, which was a positive outcome. Then, with my first letter — though it’s not a very conventional short film — because it received a National Award, people could more easily consider it a film with a certain level of seriousness.

In India, the National Awards used to be taken very seriously at one point, so people would take you seriously. Unfortunately, though, over time, the National Awards has been losing its worth.

A still from 'B and S'.

A still from 'B and S'.

These personal essays/letters mark a departure from your previous films/documentaries (some stories around witches, The Waterfall, etc.). Did you intend it as a trilogy?

It is a very natural and impromptu process. The letters just appeared one by one, first in my mind, and then they were written through images and sound. I think there will be many more letters in the future. The first letter was in 2014 (Kankee O Saapo), so this kind of expression has always been close to me. With commissioned films, though, you have to choose a style, which also serves the purpose of the film. That’s why my other films are different from the letters.

How much of B and S is autobiographical? Throw some light on its LGBTQIA+ theme.

Actually, B (Biraja) is my dear friend and we have been friends for the last five years or so. She’s younger to me by 10-12 years. I have seen her get really suffocated in this city where she lived, in Bhubaneswar, where I live right now. I’ve also seen how she would struggle through the desire of, at least, getting a close friend, a lover, some compassion and also the safety of home and a city, how she found S (Saisha) and how they found trust in each other. They were really desperate to have a home, a safe space for them where no one would question them. They shifted to Delhi to make their first home. They are not lovers, they are friends. And I have seen them build and convert that house into a home, fight over small things, talk about deeper questions and conflicts and resolve them, get angry with each other but also care for each other. The tenderness of these kinds of friendships really touches my heart.

At this moment, when we are going through such crises in the world, people are homeless, people are really struggling for belongingness, homes are being taken away, people are migrating from place to place, wars happening, you just wake up in the morning and think how to just calm down and be centred. These are the times when you forget to talk about tenderness. I thought before this friendship fades away because of the roughness of the world, I should just record it and keep it in my letter so that it will be safe there. Their identity as trans woman is there but it wasn’t the core of the film. I don’t believe that one needs to be stuck with one gender identity. There should be enough freedom to explore and understand oneself. And so, this expression is really important for me, even as a heterosexual woman.

A still from 'B and S'.

A still from 'B and S'.

Tell us about growing up with your grand aunt and your conversations with her.

That makes me smile whenever I think about my grand aunt. She passed away in 2013. Because my father had a banking job, I lived in various cities. We lived in Baripada, a small town, for eight years. My maternal uncle’s house was 50km away where my grand aunt also lived. She didn’t marry and lived alone. When I was an infant, I spent a lot of time with her and my grandmother, since my mother used to work in the city, five hours away from the village. So, they really took care of me. That’s how I was very connected to her, and to the ethos of the Adivasi household. She gave me all the Ho community learnings. After my grandfather left, she really was one of the pillars of the house. A lifelong friend to my grandmother. I spent most of my time with her, taking the sheeps and goats to the paddy fields; we are from a farming background. She taught me about nature, trees, river, ponds, how to communicate with people and trees, birds and animals. I felt that she was born to just love me. That kind of love and affection you hardly get to see anymore, even from your very close friend, partner or even your children. She used to tell me that when I move cities or marry a boy, I’d forget her. I’d laught it off but I did forget her a little when I shifted out. I used to think, you can’t forget people for love is a continuous feeling, but now I understand that love can be a choice and you can forget someone.

What came first: the images or the story?

The images came first, and then the letters were written. For the first two letters, the footage was originally meant for other purposes and other films [project City as a Studio]. After some time, the letters were constructed. With B and S, it’s a bit different, though. Much before shooting the film, I had the images of B and S, along with other characters like the sea, the parrot, and the tree, in my mind. That multiple images run simultaneously signal my thought process, which works across multiple timelines. The divided screens will also continue to appear in the letters. It started with two folds, much like how you fold a paper letter. But now, it’s evolving through many folds and has become a primary structural element in these film essays.

A still from 'B and S'.

A still from 'B and S'.

Trees and the sea are recurring motifs in your films. Tell us about the idea behind the cutout parrot in this one.

I was always close to nature as a child and my grand aunt really lit that spark if connect with nature for me. I started communicating with the natural world around me. I have an earthen parrot in my study, where I read, make films, edit films, talk to my friends. I have a connection with the non-living bird on the table. I always think the parrot is listening in to us and would tell visiting guests come, ‘this is a recorder, this parrot is recording everything. So, please be careful when you are speaking.’ In the film, Biraja has done those doodles, the lines and drawings and the origami has been done by Saisha. Something that you do with your hands and you are so connected with that psychologically and emotionally. And that helped me narrate the film, the love-relationship connection, the fluidity of it. I’m very conscious of the presence of the sea since my childhood. And my music teacher lived just next to the sea and would always tell me stories about sea and trees. In my maternal uncle’s village, I spent a lot of time under the shadow of a twin mango tree, neem tree and bamboo bushes. In the cities too, I’d always look for a house overlooking a tree. Right now, there’s a teak tree next to my house and we have a six-year-old friendship, a number of birds, squirrels, civet cat, rats, snakes come to it.

Ambient sounds play a great role in propelling your films.

I grew up close to nature, the rain sound, rustling of trees, the sound of nature drives me crazy. It is very melancholic to me. Sometimes when it rains, I cry. I become very emotional. Everything gets drenched and there’s this beautiful tenderness in the earth when it rains that softens my heart. I used to sing quite often. I had learnt singing, I trained in sound recording. I listen intently and use the sound in design in a very informed and creative way. For me, everything comes together with one distinct memory of an image or a sound. Image, sound, different timelines…everything is together. And silence has this loudest sound to it. It’s very difficult to work with silence, to have silence in your life or in a film or in a relationship or in any kind of connection. Silence can give you a lot to listen to in the ambience and surrounding, it is a very good practice. It gives me a lot of joy and it gives the film or a story a lot of natural and ethereal canvas. I love to listen to it carefully and catch the feeling of it, how tender or aggressive or melancholic it is.

A still from 'B and S'.

A still from 'B and S'.

You are doing cinematography for the first time on a film of yours.

Yes, that’s true, because it’s a very, very personal essay and I didn’t want any outside intervention. It was a courageous decision on my part because I was not confident about it. While I did a bit of camera in all my films, I would just take the camera and shoot a little bit and most of the parameters were set by the DOP. But when you shoot a certain story from the beginning till end, it’s a very different kind of relationship with the story and a very different kind of responsibility on you. The previous essays/letters were shot by my ex-husband. So, in them, people are not talking, they are emoting. I used available light. The intensity of light would accentuate their skin and their emotion on face. And I used such camera angles to see the body in fragments. It’s like the way you read a letter and imagine someone’s face, the film essay is structured like a letter.

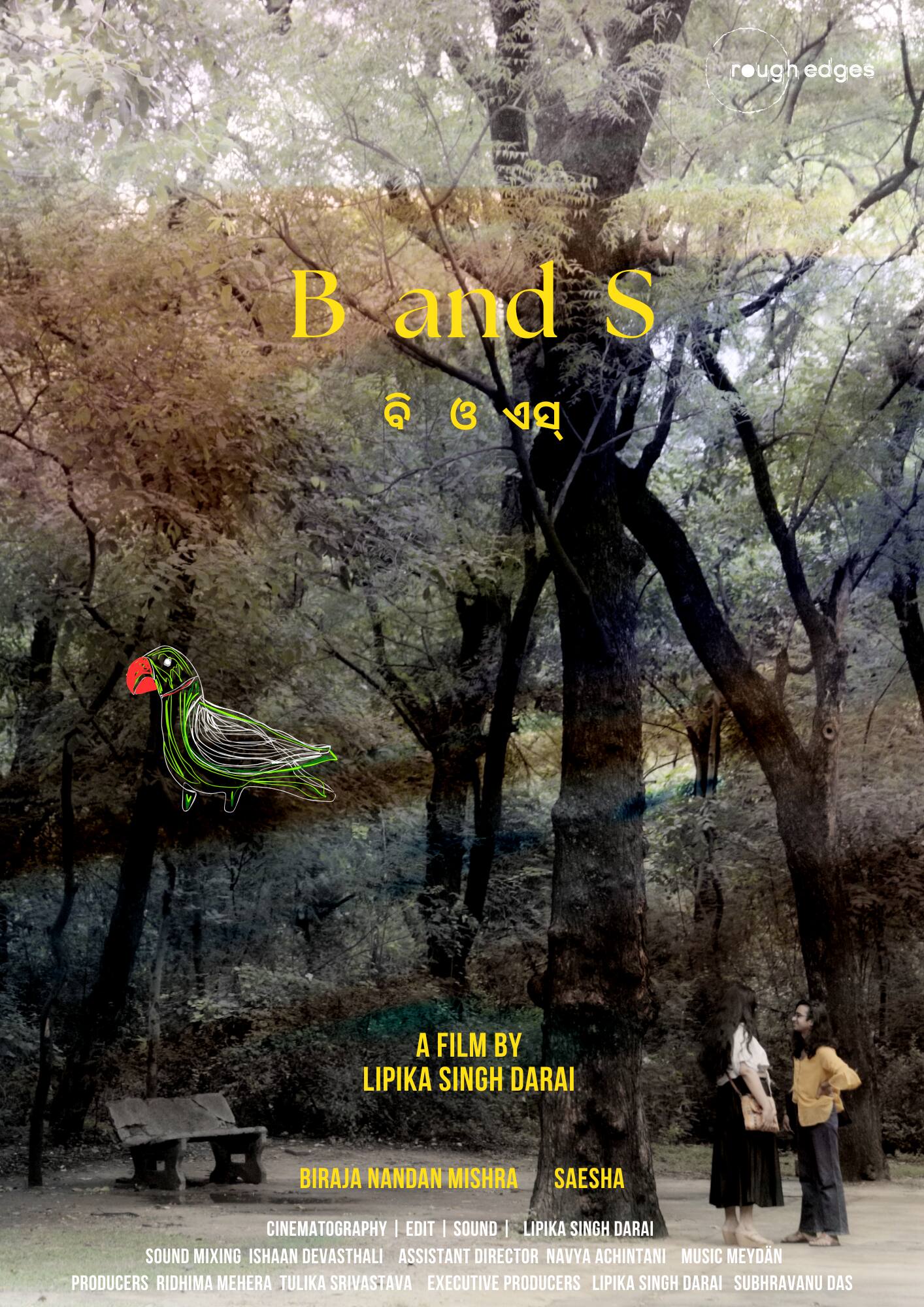

The poster of 'B and S'.

The poster of 'B and S'.

Tell us about your debut fiction feature Birdwoman which you are developing with the Hubert Bals Script and Project Development Fund 2023, the same fund that Payal Kapadia had received for her feature All We Imagine as Light.

In 2017, I thought I should make Birdwoman, because flying was a continuous thing in my dreams. I’m a lucid dreamer, I can dream multiple dreams at a time. I’ve also mentioned it in the film B and S. At some point, after making stories around witches and other films, I thought I had a story in my head and I thought this would be well portrayed in a fiction film. Three producers almost came on board. But something or the other happened and the film didn’t happen. I was really disheartened but I’m so happy that it didn’t work out that time and finally I could revive that film which is very close to me and I had a chance to develop it with Hubert Bals Fund. It is about a woman who feels that she can physically fly but she has never done it. But the film is about love, sexuality, understanding your own body, what does love mean, what is the intensity of love, lust and desire. I got a lot of time and recognition because of the fund.

Initially the form of the film was very narrative, but I understood that I’m not a linear narrative person, that is not me, the form and style is evolving, it’s a continuous process. There are many dreams and layers, many landscapes of dreams, and a mythical bird, it’s a magic realism film. This will be my first feature-length fiction film, I have mostly been making documentaries. From the pool of around 760 scripts, 10 got selected [for the Hubert Bals Fund] after much analysis and debate over your story. It’s a very competitive fund but I feel that many prominent filmmakers across the world have got it when they have started out. So, I feel really elated.

You’ve said you express yourself better in Odia instead of your mother tongue, Ho language (which is not yet part of the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution). Do you ever feel the urge to explore the community/language through your films?

Yeah, of course, I express myself better in Odia, not even in English, since it’s not my primary language. I speak and think in Odia, my schooling was in that language. I never got a chance to learn or the opportunity to speak much Ho when I was with my grandaunt and grandmother in the village. My parents spoke, but they didn’t get to teach us because Adivasis (tribal people) are looked down upon and when you speak in this language, people would ask: ‘Oh, you are Adivasi. Which Adivasi? Which community?’ My parents tried to hide it up to certain extent. My generation people are away from the villages, living in the cities, and that’s why they do not get proper exposure to the culture and the language and the ethos of their communities. And when you do not have that, it is very difficult to make a film around it. Besides, people who don’t respect the Adivasi communities tell me to archive them. Why? I don’t like that thing. So, I am very careful that when I do a film, I should understand it properly, it should be close to me. I’m waiting for the correct time when I’d know my purpose.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.