The 77th Cannes film Festival is about many firsts for Indian independent cinema. If Payal Kapadia has made history with her film All We Imagine As Light, vying for the top prize Palme d’Or, and putting India back in the main competition after 30 years since Shaji N Karun’s Swaham (1994), her Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) batchmate Maisam Ali’s personal film on Ladakh, In Retreat, has achieved the feat of being the first ever Indian film to be selected in Cannes Film Festival’s sidebar segment, ACID (Association for the Diffusion of Independent Cinema). The parallel category has existed since 1992, like the other sidebar categories Director’s Fortnight and Critics Week. Some of the early films of Claire Denis have been shown at ACID.

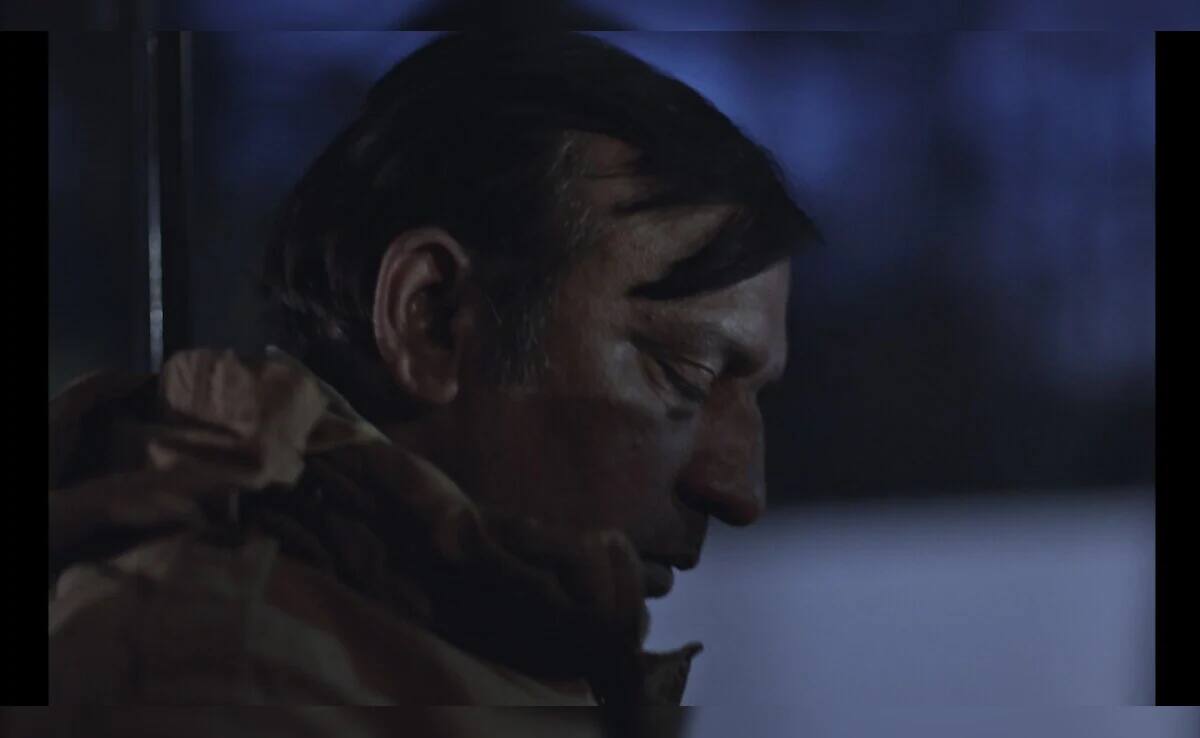

Harish Khanna in a still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions/Barycenter Films)

Harish Khanna in a still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions/Barycenter Films)

Kapadia and Ali also belong to the infamous batch of FTII that carried out the institute’s longest student protest, over 139 days in 2015, against the “political” appointment of Gajendra Chauhan as the institute’s new chairperson. The two batchmates were also divided on the protest. While Kapadia was at the forefront of the protest, even charge-sheeted for it, Ali had a “mixed response” towards it.

“During the FTII protest, I was doing dialogue project for my thesis film. While the student community eventually helped me, they first told me to stop the project. I said, you can’t tell me to stop my film because the protest was happening. For the dialogue exercise, we had to create our own set for the first time, call actors, arrange logistics, all those things take time, so I couldn’t cancel. I had a mixed feeling about the protest. Of course, in spirit and solidarity, I was with the protest because heads of educational institutions should be selected on the basis of merit not by political leanings. But I also felt the protest was going on for a long time, and I come from a normal middle-class family and we have to finish our courses, go out and work to earn money. I felt that a lot of people shouldn’t behave like privileged kids about classes being cancelled. But, then, all movements have these kinds of inner criticisms, in the larger spirit, of course, I was with the student’s protest,” says Maisam Ali, 35, for whom it was a dream to get into this “magical place called FTII where people are talking about dreams, stories and images” when he was pursuing engineering at Delhi College of Engineering and was clueless about his future.

“You also realise that filmmaking is something very serious. It has to be studied and you have to invest your time,” says Ali, who was accepted into FTII in 2012-13, where the discourse on “realism, not realistic cinema” drew him to cinema. That’s where he pored over Yasujirō Ozu’s Asian and Buddhist way of life in cinema and poetic, mundane, simple, humanistic filmmaking, much like Abbas Kiarostami’s Iranian films. That’s where he was gripped by Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), “a film trying to capture time, an insurmountable task”. Kiarostami’s films taught him how he can cut the viewer’s touristic gaze of his native place by mining for stories in the depths of his own soul and experiences. And that’s where he realised that cinema doesn’t always need villains and grand narratives, “that we can tell our small stories and it also matters”.

Taking from Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s verse If I were Another on the Road, Ali has made a personal film, a slow burn, showing Ladakh in a way never seen before. Ali does away with linear narrative and begins the film in medias res, his protagonist is an inside-out flâneur, observing without, reflecting within.

The shooting during the “blue hour” lends the film a visual grammar much like Achal Mishra’s third film Ri, but Mishra’s gaze, for a good part, unlike Ali’s, remains of an outsider struck by the colossal, sublime beauty of the place. Ali, the local, wanted to show Ladakh as he has seen it up close, through mid-shots and big close-ups, foregoing the wide-angle panoramic shots of the gargantuan mountains for the narrow by-lanes and alleys, congested marketplace, crowded buses, construction sites, migrant workers and rowdy youth, showing that which is not beautiful, while eliciting questions of us versus them, of home, belonging, journey and disconnect. Ali, in his protagonist Harish Khanna, aided by cinematographer Ashok Meena’s adept lensing, achieves a Raskolnikov-like interiority and stream of consciousness. The crime of Ali’s nameless protagonist, who arrives for his brother’s funeral one day too late, was that he “went away” and his punishment is that he can “never return” even though he does physically. The sense of an ending becomes him.

Ali, the Iran-born Ladakhi filmmaker, talks about home, FTII, and his debut feature, co-produced by Varsha Productions, Barycenter Films and Salt for Sugar Films, at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival. Edited excerpts:

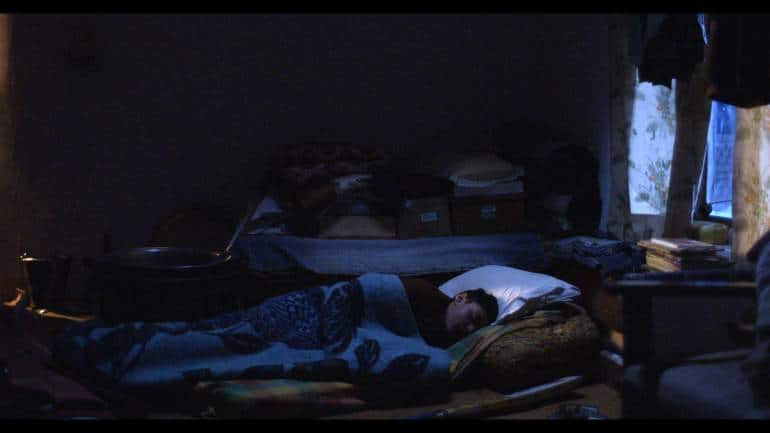

A still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions/Barycenter Films)

A still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions/Barycenter Films)

FTII is where you came into your own, creatively. Did you also become more of a political being there?

It’s a good question because what happens when you go to FTII, you start to look within, as with any sort of artistic practice, you have to look within. I’m not a hardcore political guy but questions of identity and belonging do assail me.

Personally, my preference is to not make films about a social issue or make a political essay, no kind of messaging, I just like to make something which is honest to me. I don’t like that kind of ‘boxing’ — social/political issue-based film — because, as an artist, all we want to be is free. The space for arthouse cinema is shrinking everywhere. Even film festivals, the place where personal works are given a chance, are also becoming very, very difficult to get into. We have to fight for our space, because art cinema is a huge part of the history of world cinema. So, I’m really thankful that Cannes’ ACID section gives spaces to such films.

You grew up in Iran and then moved to Ladakh?

It was a common thing in the 1980s (for people to move out for work and return). My father is a physician, so he went to work in Iran and I was born there. I lived there for just seven-eight years. After that, we moved back to Ladakh, and later, I moved out for studies and work. My parents are from Ladakh only and we are Ladakhi Muslims. But some newspapers have described me as an Iranian Indian filmmaker, that is problematic because I’m an Indian filmmaker.

Yes, I can connect with the smaller aspects of Iran’s culture because I’m also Shia Muslim. To give you an example, in one scene in Kiarostami’s film Where is My Friend’s House? (1987), when the boy wants to go give the notebook to his friend and asks his mother for permission, who doesn’t understand, and he climbs up when the grandmother says, remove your shoes, it will become najis (dirty/impure). It has a religious connotation, and it’s very relatable. In that small scene, you realise that it is a religious, orthodox society. I also had similar upbringing.

Where is home?

Like most of the people in today’s world, I don’t know where is home. But if I have to say, when I hear stories about my great-grandfathers, who were traders, who used to travel with horses and camels for trans-Himalayan trade, that landscape where they used to travel, stop, have picnics and sing, that is like a home…a fantastical kind of a home for me.

The film’s title In Retreat has a dual meaning of both going away from something, a withdrawal and a break, time away from daily life; while the Urdu title is Be-qayaam (without stay/a place to rest/for solace)?

Yes, yes, rightly as you pointed out, In Retreat has the meanings of rest and restlessness. My film is about being there and not being there. Is the person actually there, was it all a dream? What a nightmare and what a sad story of somebody if this is his last memory of the place. Dreamy and nightmarish at the same time. So, In Retreat has this double meaning, where he’s trying to belong, and trying to have solace, find rest but at the same time, it’s also without stay, rest or solace.

A still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions/Barycenter Films)

A still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions/Barycenter Films)

Could you describe the childhood incident which influenced the plot of this film?

I was around 12-13 years old when I saw a glimpse of somebody similar to the protagonist of my film, or, perhaps, I just heard about him, that such and such person has come back in this family. The family was not welcoming of him, because it so happens in small towns that when people go away and return, they are not part of the community any more, they are treated like outsiders, because they were not there during the tough times, didn’t take care of the parents/ family, etc. This was a middle-aged person who’d returned from London, I thought there is a sadness about him. Maybe, I thought, he is a distant version of myself in some ways. Also, the landscape, the parts where I have shot, old parts of the town Leh is an interesting place comprising a lot of ruins and those kinds of texture where you might bump into a person like that who has been away for a very long time and has come from a far place.

Why did you have Hindi as a language of the film? Your protagonist (Harish Khanna) speaks in Hindi, with brief spattering of Ladakhi, despite hailing from there.

Yes, he’s from there, but he’s also not from there. And, maybe, he also doesn’t want to give away that he’s from there.

I chose Hindi because I am so disconnected with my own language, I can’t think, speak or write poetry in Ladakhi, because I was not in Ladakh for some period. A lot of people in Ladakh speak in Hindi. I don’t have that one strong language to call my own. Growing up, I couldn’t understand or relate to the songs, which had difficult vocabulary.

Your film has a distinct visual grammar. The cinematographer Ashok Meena is also ex-FTII, was he an obvious choice?

Ashok was from outside, for him it was a beautiful place, he was interested in taking a wide shot, but I was not interested in that. It was important for me to not have touristic images of Ladakh. I was radical. I wanted to look at the landscape and this character in the landscape objectively. I wanted to shoot in the night. I didn’t want to show any kind of beauty. My visuals had to be personal. I’d go to pockets of places where I have some memories. I wanted to show something very interior, experiential to myself. Ashok had also worked before there in that area. He was making his own documentary there. And there will be a certain standard that FTII cinematographers bring.

The music used is also not the music of the land, not Ladakhi music but Western Classical. How come?

Like the imagery, the music of Ladakh can also become touristy, and I don’t have that kind of a relationship with the music. Early on, I’d have listened to Hindi songs, and later, music from all over the world. I could neither connect to that kind of [Ladakhi] music nor find something suitable. The classical music used is a piece covered by Bach, not his original, the same piece has been redone by Glenn Gould, I felt the music of the piece echoed the film’s mood.

Harish Khanna in a still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions, Barycenter Films)

Harish Khanna in a still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions, Barycenter Films)

Harish doesn’t look like he’s from Ladakh, were you trying to break a stereotype by casting him?

I wanted to cast Robin Das, who’s from NSD (National School of Drama, Delhi), but he’s in his 70s and we were shooting during COVID. My seniors suggested Harish. I like the way he is. The character required a certain kind of interiority, loneliness, vulnerability. Harish is a very good cinema actor, an interior actor. His being is quite close to the character.

There are a lot of people, a lot of Muslim families in Ladakh, the Buddhist families, they all look different. It happens with me also when I go home, people don’t believe me that I’m from there. It is again about ‘boxing’ things, that you’re from Ladakh, so you have to look a certain way.

In the modern world, we are all displaced. And because I also come from a place which has a very strong landscape, when you go to some other place, you don’t feel at home anywhere. And after living in the city, you can’t be at home in a town either. The insider-outsider question is as philosophical as it is political.

Recently, Sonam Wangchuk went on a hunger strike, protesting with thousands of locals, demanding statehood for Ladakh. The same Ladakhis who were elated in 2019 after becoming a Union Territory are now disillusioned. Where do you stand on that?

We have been demanding for Union Territory for a long time, but the idea was to have a UT with (own) legislature, we wanted the governance should be in the hands of the people who are living there, that is very important and that was largely there when we were part of J&K also, the Hill Council and a lot of councilors, so decisions were made by local people over there. Right now, the problem is, people are not able to take decisions for themselves. So, it is a very valid demand, that should be the case and, hopefully, that would be the case.

A still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions, Barycenter Films)

A still from 'In Retreat'. (Image courtesy Varsha Productions, Barycenter Films)

In today’s time, as a Muslim and a Ladakhi Muslim, do you feel twice removed from mainland India?

India is a very beautiful country, but yes, of course I feel removed, I’m not the main character anywhere. I always have the feeling that I’m on the periphery, the outsider. But, in my case, that is because of my own unique situation and past as well and I take it in a very positive sense because I get to see things from a different perspective, like in cinema, you take shots from different angles. It helps to understand each other’s point of view. Ultimately, art is about that, sharing a connection.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.