One day at Pune’s Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) library, while Amit Dutta was engrossed in a book on Western painters, a professor told him, “Amit, don’t read too much about paintings. Just look. Don’t get caught up in Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, or these theories — just see.” Dutta, smiled to himself, for he’d find the ideas more intriguing than the paintings themselves. However, over time, Dutta realised the value of that advice. “I began dividing my time in the library into two parts: during one half, I would consciously refrain from reading and simply immerse myself in the act of looking at paintings; during the other half, I would only read. This balance deepened my connection to art, teaching me to engage with it both intuitively and intellectually,” writes Himachal-based Dutta, 47, in an email.

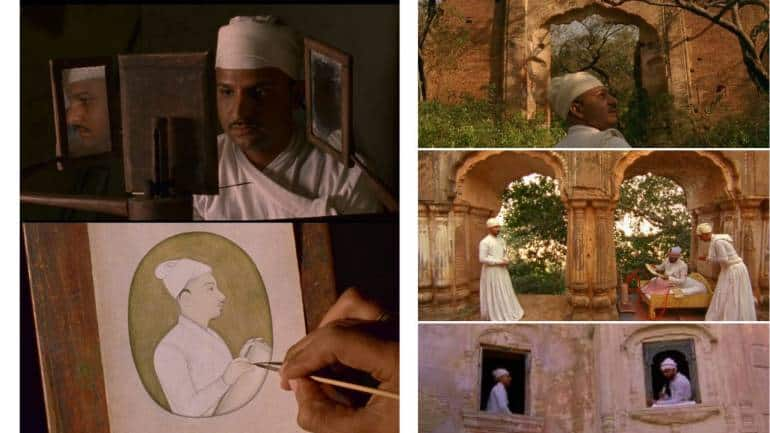

Amit Dutta, akin to the protagonist of his film The Unknown Craftsman, is a singular artist. The 40-plus films and six books old filmmaker is a prominent name in independent cinema on the international festival circuits but is still obscure back home, his films don’t release in theatres or OTTs. “The exhaustive breadth of Amit Dutta’s films refuses easy summation,” to quote Mani Kaul’s daughter Shambhavi Kaul. The breathtaking Kramasha (To Be Continued, 2007) presents a dreamy rendition of rural life in India. Nainsukh (2010), on the 18th-century miniature painter from Guler, marks Dutta’s turn towards research-based cinema and his first film on a painter. “Intrigued by the idea of making a camera-less film”, his latest, Phool ka Chhand (Rhythm of a Flower), co-written with Kuldeep Barve and illustrated by Allen Shaw, is a hand-drawn watercolour animation on Pandit Kumar Gandharva. It has its world premiere at International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) on February 5.

“They [his films] traverse genres, moving effortlessly from crafted scenario to spontaneous encounter, from mindful self-reflexivity to ghostly magic. Art — literature, music, and particularly painting — permeates Dutta’s work. It appears as the subject of his films, yet it is also absorbed into their very material as cinematography and soundscape — as cinema,” writes Kaul.

His films are paintings in live action or animation. With almost tactile imagery. His films have had a proclivity for the painter and the painted: from Nainsukh (18th century Pahari painter from Guler); three shorts Gita Govinda, Field-Trip, and Scenes from a Sketchbook; Jangarh: Film-One (on Gond tribal artist Jangarh Singh Shyam); The Seventh Walk (on artist Paramjit Singh); The Museum of Imagination, A Portrait in Absentia (on art historian BN Goswamy, an authority on Pahari art); to Lal Bhi Udhaas Ho Sakta Hai (Even Red Can be Sad) on modernist painter Ram Kumar. Did Dutta study painting before making films? Growing up in Jammu, he was exposed to discussions about Basohli paintings but hadn’t studied or seen them extensively because they weren’t widely available. A young Dutta would be, instead, fascinated with children’s books like Chandamama and their captivating illustrations. His real exposure to painting happened at the FTII library, where he spent countless hours studying paintings.

Dutta’s approach to sound design has been intuitive, too, rooted in a simple yet profound principle: “the role of sound is to suggest what lies beyond the frame, to evoke the unseen. Film inherently points to something larger, a vast, interconnected phenomenon that cannot be fully captured visually. Sound becomes the bridge to that immensity, hinting at the infinite and grounding the audience in the expansiveness of the experience,” he adds.

In this final installment of a two-part interview, Dutta deliberates on his practice, cinematic influences, David Lynch and his advice to younger indie filmmakers. Edited excerpts:

ALSO READ: ‘Kumar Gandharva was not just a musical genius but also a profound scholar & thinker’: Amit DuttaYou graduated from FTII Pune and taught at National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad. Does formal education help in becoming a filmmaker?Everything helps; if you go to a film school, it is a unique experience, and if you don’t, that is also unique. Formal film education, especially at national institutes, offers a distinctive environment for growth. I have tremendous gratitude for FTII and the vision that led to the creation of such [public] institutions. While it might appear formal from the outside, it is, in fact, quite an informal, instinctive school.

There’s a famous saying that cinema cannot be taught but can be learnt. In the end, filmmaking is an intensely personal journey, but the environment of a film school fosters the discipline and curiosity to explore that journey. It’s a safe space to fail, experiment, push boundaries without fear, refine your voice, and develop the courage to express yourself authentically.

I read Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game (1943) while studying at FTII, and it had a deep impact on me — I think it formed the basis of my thinking. In the novel, scholars in the province of Castalia engage in an intricate intellectual pursuit, where the game’s sign language and grammar form a highly developed system, drawing upon multiple sciences and arts. It weaves together mathematics, music, philosophy, and art into a grand, symbolic structure. This idea of interconnected knowledge stayed with me, shaping how I approach my films’ subjects.

My work often feels like my own private Glass Bead Game, where different disciplines — history, music, visual art, and written word — interact in an ongoing dialogue. But, like Joseph Knecht, the novel’s protagonist, I also struggle with the question of whether this pursuit has any tangible value beyond its own intricate beauty. Is it enough for knowledge to simply exist in its refined form, or must it have a direct impact on the world? That tension is something I constantly grapple with.

At the same time, my work is deeply rooted in vernacular knowledge systems — ways of thinking and knowing that are tied to the land, culture, and people. These aren’t just abstract ideas but lived, embodied experiences shaped by their environment. Whether it’s Nainsukh, the 18th-century miniature painter from Guler, or Kumar Gandharva, the 20th-century classical vocalist, I am drawn to subjects that reflect this deep connection between thought and place.

But it’s not just about the subjects themselves — it’s also about the form they take. Each project feels like an invitation, not just to tell a story, but to engage with an entire way of seeing and understanding the world. In that sense, my films are not just part of a Glass Bead Game of interconnected ideas but also an exploration of knowledge that is instinctual, felt, and inseparable from the world it comes from.

You’ve said you want your films to move in a direction like Alain Resnais’ films did. What about his style/films is striking?Alain Resnais’ control over form and his extraordinary clarity of mind in exploring the most abstract, almost inarticulable realms, is something I greatly admire. While I appreciate most of his films, My American Uncle (1980) is my favourite. What I deeply admire about this film is its innovative approach to blending fiction, non-fiction, and the creative essay. The film explores human behaviour, psychology, and the interplay between biological instincts and societal influences. Through this approach, Resnais creates a layered experience, where the personal stories of the characters become a canvas for larger philosophical and scientific questions. His ability to maintain emotional depth while engaging with complex intellectual ideas is remarkable. This seamless integration of narrative and abstraction, of fiction and essay, is what I find most inspiring and something I strive to explore in my own work. It was interesting to read Olaf Möller’s piece for Rotterdam, where he described Phool ka Chhand as a ‘creative essay’. I was quite pleased to see this, as it resonated with what I had hoped to achieve.

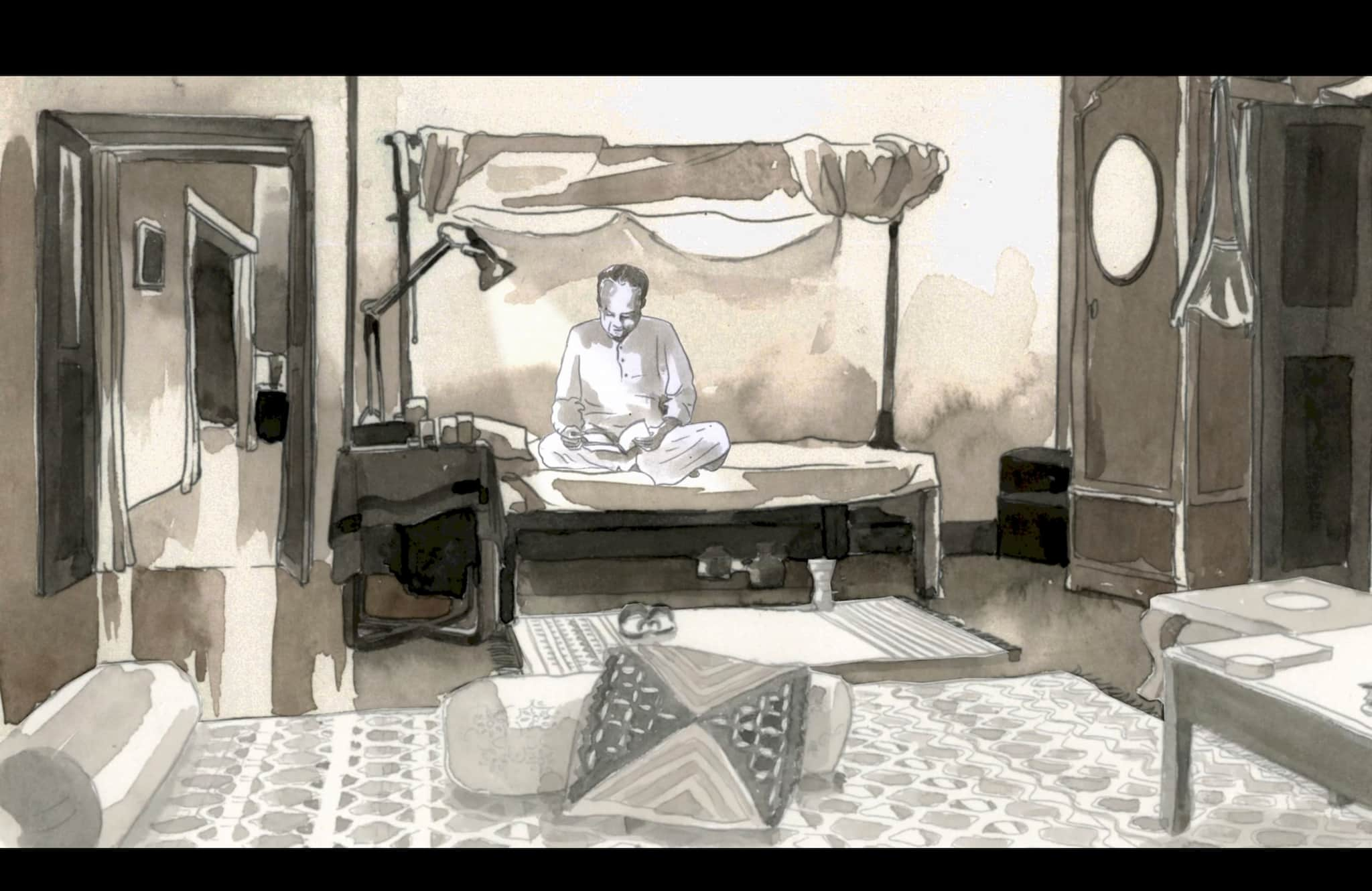

Pandit Kumar Gandharva in a still from 'Phool ka Chhand' ('Rhythm of a Song').Sergei Parajanov, Robert Bresson, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani — what common thread connects these filmmakers which inspires you?

Pandit Kumar Gandharva in a still from 'Phool ka Chhand' ('Rhythm of a Song').Sergei Parajanov, Robert Bresson, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani — what common thread connects these filmmakers which inspires you?If I were to reflect, one thread that connects filmmakers like Sergei Parajanov, Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani is their ability to engage deeply with the collective consciousness while maintaining an intensely personal, maverick approach. They work within traditions, whether cultural, historical, or artistic, yet transform those traditions into something entirely their own. This interplay fascinates me — the way they balance the instinctive and the intellectual, the folk and the classical. Parajanov’s imagery, for example, feels like the instinct of a folk artist who draws from centuries of myth and tradition, yet his craft reflects the rigour and discipline of a classical master. Similarly, Bresson’s meticulous minimalism transforms spiritual and moral dilemmas into something universally resonant, all while being deeply personal. For me, this intersection of tradition and individuality feels enriching. It’s about acknowledging the collective history and roots that shape us while also daring to articulate something personal and unique. It’s the “best of both worlds,” as you put it: a place where deeply rooted traditions become fertile ground for maverick innovation.

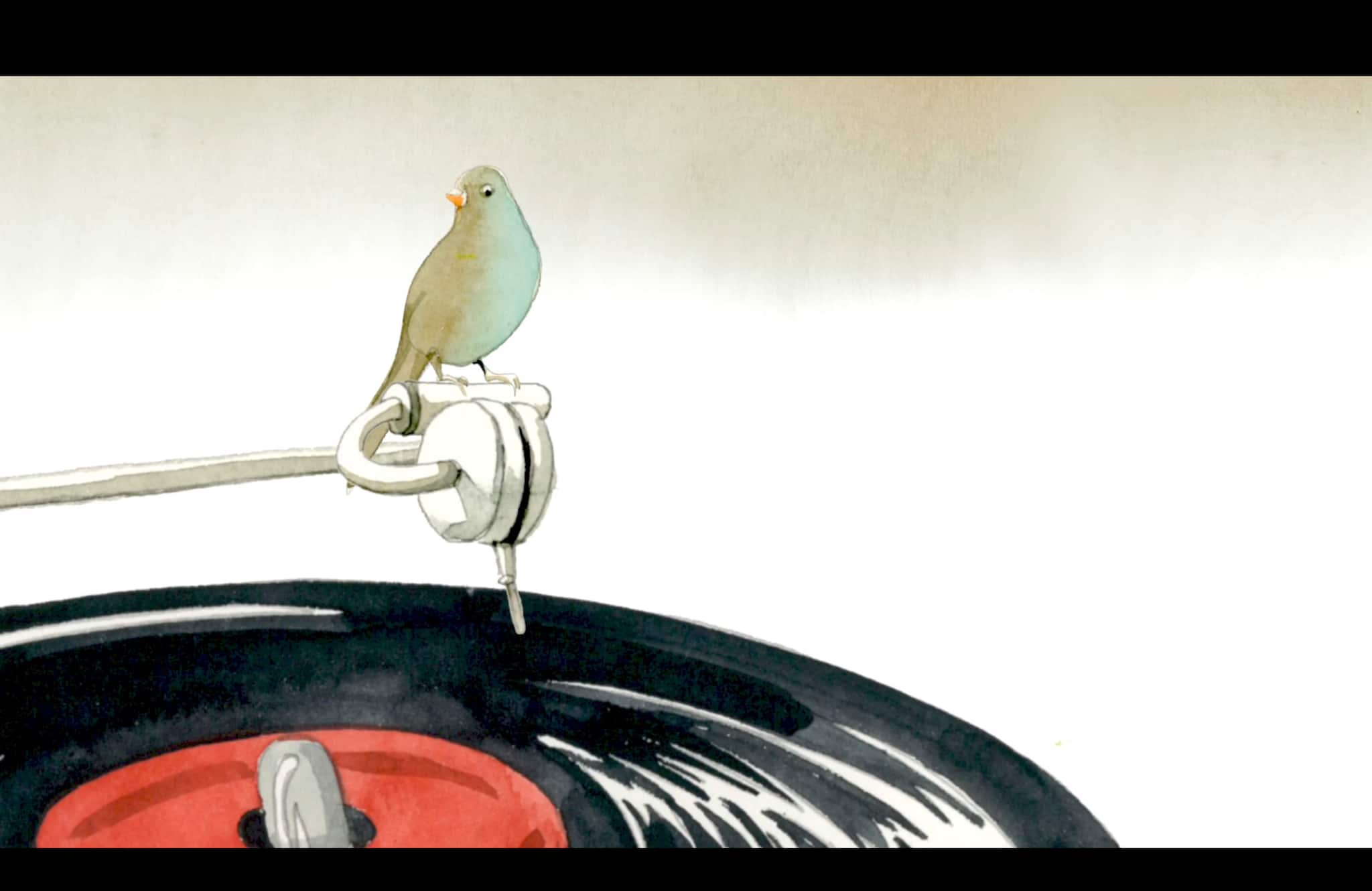

A still from 'Phool ka Chhand' ('Rhythm of a Song').A bird, like a stylus, sits on a tonearm to play a vinyl record in Phool ka Chhand. In your films, there’s ‘a fixation on everyday objects displaced from their quotidian functionality’, like the works of Surrealist artists. One such, David Lynch, died last month. Any film of his that you like? Lynch also said that solitude and meditation can help calm the mind and increase creativity; solitude — being a recluse, away from the noise/industry — has informed your creative output, too.

A still from 'Phool ka Chhand' ('Rhythm of a Song').A bird, like a stylus, sits on a tonearm to play a vinyl record in Phool ka Chhand. In your films, there’s ‘a fixation on everyday objects displaced from their quotidian functionality’, like the works of Surrealist artists. One such, David Lynch, died last month. Any film of his that you like? Lynch also said that solitude and meditation can help calm the mind and increase creativity; solitude — being a recluse, away from the noise/industry — has informed your creative output, too.The David Lynch film that has left the deepest imprint on me is The Straight Story (1999). I still hold it as one of his finest films. Perhaps, in making it, Lynch wanted to reach into the quiet depths of himself — and what emerged was profoundly beautiful.

As for meditation, it has been a thread running through my life since childhood. Initially, I was drawn to it for a practical purpose: I wanted to improve my concentration for competitive chess in school. Someone suggested Zen meditation, so I bought a book and began practicing. I must have been 12 or 13 at the time. Since then, I’ve rarely abandoned it — perhaps, only for a few years during my time at FTII, though even then, Zen remained a quiet undercurrent in my life.

Now, for many years, meditation has been a daily ritual, a sacred space I return to without fail. My only desire as I grow older is to expand this practice, to devote more time to stillness. When the time comes and death arrives, I hope to embrace it not as an end, but as an infinite meditation — a merging into the boundless quiet.

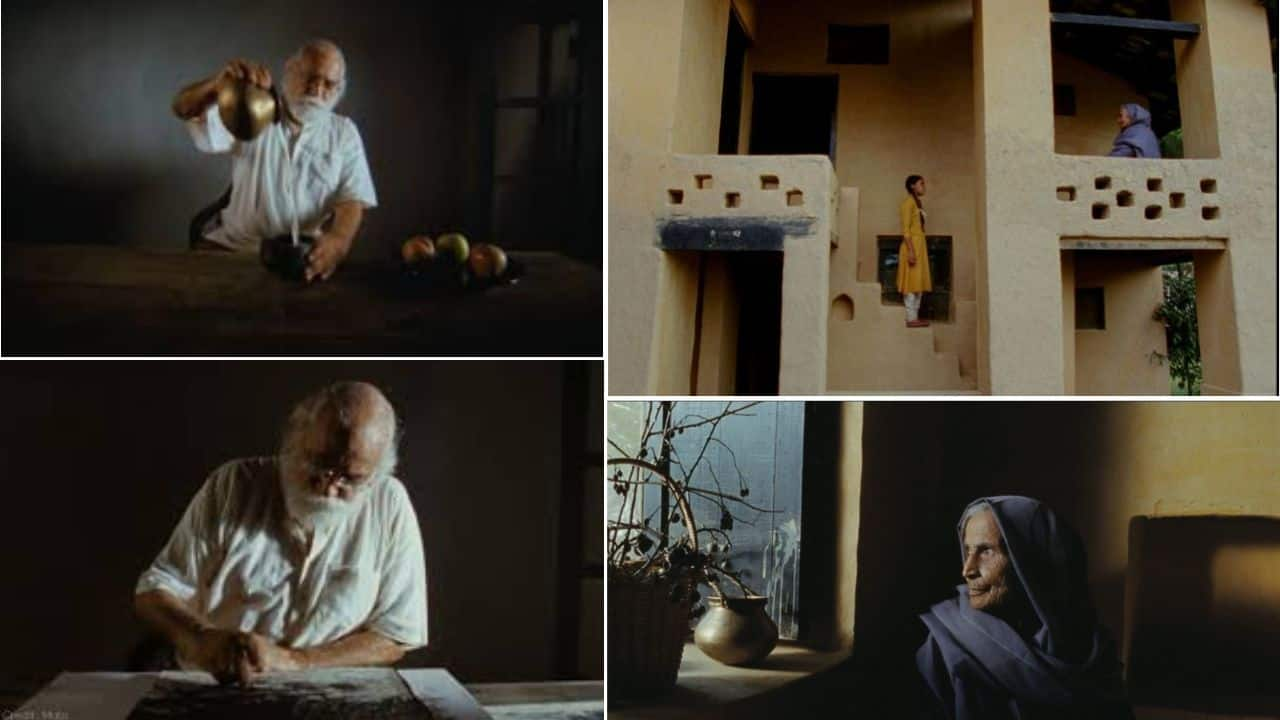

Stills from the film 'Nainsukh' (2010), directed by Amit Dutta.Many of your films have been both ethnography and biography, do you see it as an artist’s responsibility to document one’s culture in their work, and is that a historical act? Do you see cinema as a medium to educate/instruct?

Stills from the film 'Nainsukh' (2010), directed by Amit Dutta.Many of your films have been both ethnography and biography, do you see it as an artist’s responsibility to document one’s culture in their work, and is that a historical act? Do you see cinema as a medium to educate/instruct?As I analyse my own interests — not entirely consciously designed — they seem to be driven by an impulse deeply rooted in the human civilisational urge to create and find beauty amid chaos and violence. That impulse moves me more than anything else.

For instance, when Nadir Shah attacked Delhi and there was violence everywhere, it is said that the great Persian scholar Tek Chand Bahar saw an opportunity amidst the destruction. He reportedly added new words to the dictionary he was compiling by asking the invading Iranian soldiers for their meanings. This story — the human capacity to seek and preserve knowledge and beauty even in the darkest times — profoundly moves me.

I don’t believe that cinema should aim to educate, instruct, or entertain. Cinema exists for its own sake — a medium through which we can explore beauty and truth, or at least engage deeply with these ideas. What I’ve realised over time is that this aspect of cinema — the ability to reach for something transcendent — seems to emerge most clearly in low-budget films made with personal initiative and without external expectations.

Your films lie outside the commerce vs arthouse binary. How do you define your cinema? Who do you make films for: yourself or do you seek an audience subconsciously?It’s difficult for me to define my cinema fully, as I haven’t yet grasped the complete sense of my own instincts. However, one thing I’m absolutely clear about is that I don’t want my work to be a reaction to anything outside of myself. It should be an authentic quest, even if it’s not always original in the conventional sense — it must be true to who I am.

Yes, I do care about my audience, but in a quiet, sincere way. I’ve never been disappointed by the response I’ve received. I’m content and happy with what I’ve experienced. While financial struggles and the lack of resources make me a bit anxious at times, I believe the trade-off is worth it.

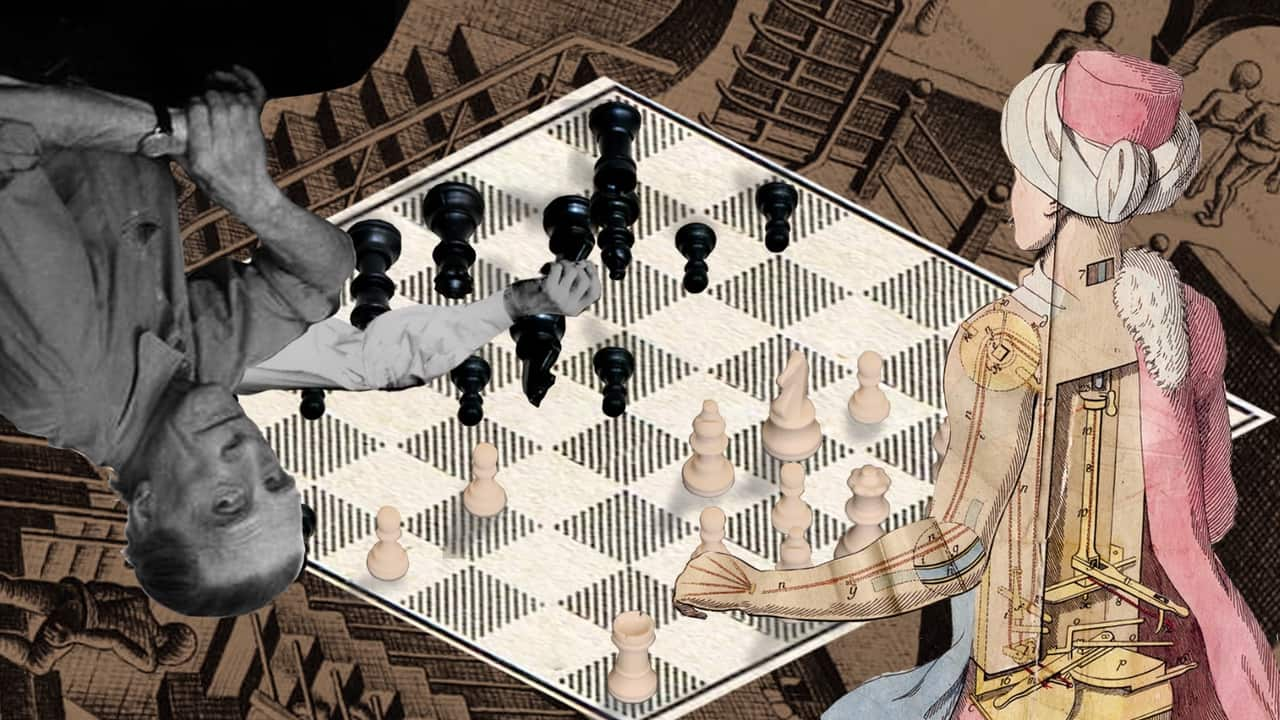

'Wittgenstein Plays Chess with Marcel Duchamp, or How Not to Do Philosophy', (2020), directed by Amit Dutta.You’ve made two animation films in a row: Wittgenstein Plays Chess with Marcel Duchamp, or How Not to Do Philosophy (2020) and Phool ka Chhand/Rhythm of a Flower (2024). For filmmakers working on paltry budgets and with small/no crew, is animation a boon?

'Wittgenstein Plays Chess with Marcel Duchamp, or How Not to Do Philosophy', (2020), directed by Amit Dutta.You’ve made two animation films in a row: Wittgenstein Plays Chess with Marcel Duchamp, or How Not to Do Philosophy (2020) and Phool ka Chhand/Rhythm of a Flower (2024). For filmmakers working on paltry budgets and with small/no crew, is animation a boon?Absolutely! I have made over 15 animation films, starting with my student projects at FTII, including my diploma film, which featured animation. I even created a short animation film in 2005. Animation gradually became a significant part of my work. However, it’s important to dispel the notion that traditional animation is cheap — it’s actually very expensive, often more so than live action, and far more time-consuming. I don’t use traditional animation techniques but rely on something very basic. The focus is on the idea and structure of the thought, not the animation technique. These are, in essence, ‘dynamised illustrations’, making the films feasible within a low budget. This style of animation can be a wonderful tool to bridge the gap between limited resources and boundless creative consciousness, making it possible to create something meaningful and resonant. But to be honest, working with a low budget and a small or non-existent crew is not necessarily a problem — it can even be liberating. I also feel that even if one has access to substantial resources, films should still be made with a sense of austerity and focus. For example, if someone receives a grant to write a book, they wouldn’t rush out to buy a pen made of gold; it’s the words and the emotions behind them that truly matter. The same principle applies to filmmaking — it’s the vision, and the passion that count, not the scale of the production.

A still from the film 'Jangarh: Film-One', by Amit Dutta.Is that the advice you, as a prolific filmmaker yourself, would give to younger indie filmmakers who find it difficult to make their second film?

A still from the film 'Jangarh: Film-One', by Amit Dutta.Is that the advice you, as a prolific filmmaker yourself, would give to younger indie filmmakers who find it difficult to make their second film?When I think about the challenges younger filmmakers face in making their films, I often find myself reflecting on my own journey. The best advice, perhaps, is the kind one gives to oneself and truly follows. In that spirit, I’ve come to realise that filmmaking is not just about directing — it’s about understanding every aspect of the craft. Learning to shoot, edit, and work with sound on my own has been invaluable. It allows for a kind of independence that keeps the process honest, even when resources are scarce. Filmmaking, in this sense, feels like writing with a pen: intimate, solitary, and deeply personal.

There’s something powerful about creating in anonymity. It’s not always easy — family and friends might not fully grasp the need to commit to this path without guarantees of success. Their support is essential, even if they don’t completely understand the process. For me, low-to-no-budget filmmaking has been liberating. It pushes you to explore platforms like film festivals, YouTube, or Vimeo, just to see if your work resonates with anyone at all. But even if it doesn’t, there’s value in simply making the film. It becomes a ritual, a quiet act of faith, like the boy in [Andrei] Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice (1986), who waters a seemingly lifeless tree every day, without any immediate reward.

The gaps between films can be long and daunting, but I’ve come to see them as opportunities rather than setbacks. They’re moments to redirect energy — towards writing, painting, or even something seemingly unrelated, like running a business or opening a bookstore. It’s important not to drain oneself by attaching too much ego to a single film or spending too much energy chasing validation. A film should exist independently of its maker, and the filmmaker must move forward, carrying lessons but not burdens, into the next project.

I often think about the kind of support and discipline one can find in institutions like FTII, but also about the importance of maintaining an independent mindset, even within such spaces. At the end of the day, filmmaking feels like a quiet conversation with oneself — full of doubts, revelations, and small victories. And, perhaps, that’s where its true beauty lies.

Stills from the film 'The Seventh Walk', by Amit Dutta.You seem to prefer solitary watching of films on laptops than collectively in theatre. The OTTs should have been a blessing for indie filmmakers like you but those have been co-opted by the ‘industry’ and commerce. How does a cash-strapped indie filmmaker survive in India?

Stills from the film 'The Seventh Walk', by Amit Dutta.You seem to prefer solitary watching of films on laptops than collectively in theatre. The OTTs should have been a blessing for indie filmmakers like you but those have been co-opted by the ‘industry’ and commerce. How does a cash-strapped indie filmmaker survive in India?These things matter a lot, and I believe that when thinkers / journalists like you begin asking these questions, the issue is already being addressed. Nonetheless, I do get emails and requests from aspiring filmmakers, many of them from families concerned about financial stability. But what do I say to them? There is no system to point to. It’s all quite random, a matter of luck. The avenues are not only limited — they barely exist. OTTs could have been a blessing for independent filmmakers, but frankly, I never even considered them. My films are not made for entertainment; they might even bore some viewers. I need the freedom to make what might be irrelevant boring films for some, and I don’t think OTT platforms would always support that. In fact, when one of my editors was working on trailers for my films — he was excellent at his job — the trailers often made the films seem more exciting than they actually were. I asked him not to make the trailers more thrilling than the films themselves because I didn’t want to lure an audience in just to disappoint them. I believe that the kind of films I make should be sought out, not thrust upon people. They should be found by those who are willing to engage with them deeply, not through flashy marketing or forced attention. This is the freedom I value in my work.

A still from the film 'The Unknown Craftsman', by Amit Dutta.With the closure of Films Division and PSBT (Public Service Broadcasting Trust) not existing in its erstwhile form, do indie filmmakers now have to look offshore for institutional / financial support?

A still from the film 'The Unknown Craftsman', by Amit Dutta.With the closure of Films Division and PSBT (Public Service Broadcasting Trust) not existing in its erstwhile form, do indie filmmakers now have to look offshore for institutional / financial support?There was a time when institutions like FTII, NFDC, Film Division, PSBT, and Doordarshan faced criticism — some called out their bureaucracy, others questioned their funding and perceived inefficiency. Yet, these very institutions nurtured some of the finest films and filmmakers in our country’s history. Over time, I believe people will come to understand just how vital these organisations are for the cultural and social health of our society. They serve a purpose far beyond cinema; they are pillars of our collective artistic and cultural identity. I deeply hope they regain their former strength because their role is irreplaceable.

Filmmakers, of course, cannot create or sustain such structures themselves. They will naturally go wherever opportunities or support exist — and so they should. My exposure to these avenues, however, is limited. What I do feel strongly about, though, is that true and sustained support for our cinema must come from within. It must arise from those who are genuinely invested in our stories and cultural identity, not just as artistic expressions but as vital components of our shared legacy.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.