"Indore could, in this reimagining, become a much more liveable and attractive city than Delhi, Bombay or Calcutta," Ramachandra Guha writes a quarter of the way through his latest book, 'Speaking With Nature: The Origins of Indian Environmentalism'. "This reimagining", to put it in context, comprises Raj-era botanist-cum-town planner Patrick Geddes's recommendations to remake the erstwhile Holkar princely state (present-day Indore) as a haven where the dichotomies of human vs nature, urban vs rural dissolve to create a sustainable yet progressive township.

A Scottish national, Geddes is one of 10 people—Indians and foreigners—who in some way opined on India's development vs environment concerns at some point in their careers, and whose environmentalist thought Guha pays homage to in the book. The 10 people featured in the book include some well-known examples like Verrier Elwin, Mirabehn and Rabindranath Tagore (and his hugely successful classes-in-the-mango-grove experiment) and some less known ones like Patrick Geddes who came to India for an exhibition in late 1914, only to find that the exhibits he wanted to showcase were drowned on their way to Chennai by a German destroyer at the start of the first World War.

Madeleine Slade (Mirabehn) with Mahatma Gandhi in 1931. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Madeleine Slade (Mirabehn) with Mahatma Gandhi in 1931. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Guha writes that Geddes "spent the winter and spring in India" from 1915-24. Sometime during this period, he explains, Geddes spent a year in the princely state of Holkar (modern-day Indore) and made suggestions for building a shrine that could be reflected in the waters of the Narmada river that runs through the city; for supplementing the city's thriving cotton trade with silk production that could be the business domain of women; for parks—including a Zenana Park, as a measure to reduce the high instance of tuberculosis in enclosed women's quarters then—and for building a nature reserve of sorts on one edge of the city. The hope was, as the opening quote suggests, to build a livable, breathable, sustainable city. (Indore features again in the book, in the chapter on Albert Howard who studied traditional Indian farming and composting techniques and described it to the world as the Indore method.)

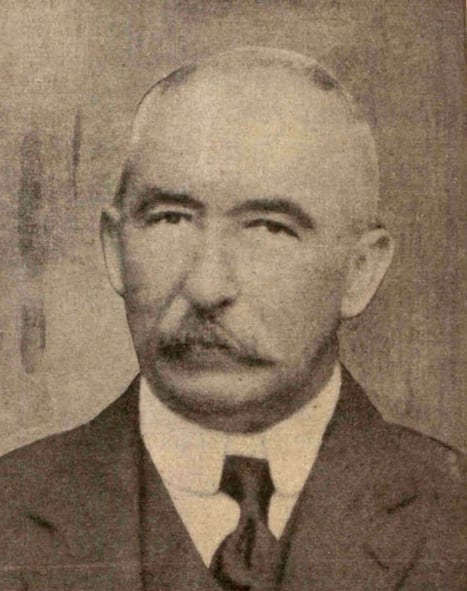

Albert Howard. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Albert Howard. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

On the surface, the central idea of the book—10 thinkers who thought deeply about India's ecological future—sounds promising. But 'Speaking With Nature: The Origins of Indian Environmentalism' is a difficult book to reconcile in at least three ways.

One, the 10 "environmentalists" featured here are really poet, freedom fighter, educationist, botanist/town planner, agriculturalist, priest-turned-anthropologist and tribal rights activist, Union minister, scientist or freelance journalist, who also have a point of view on the importance of ecology and its conservation in India. They are not all people who devoted their lives to building sustainable solutions in or for India, though most did the best work of their lives in India. They are also not always people who could shape policy in any meaningful way to conserve nature. The subtitle of Guha's book—'The Origins of Indian Environmentalism'—is also confusing. It could suggest, for example, that ecological thought or at least focused ecological concern begins in India only in the 19th century with Tagore or that present-day environmentalists can somehow trace the roots of their movements and ideas back to these "origins".

Two, Guha doesn't seem to be very interested in the impact—lasting or otherwise—of the ecological thought(s) and schemes of these environmentalists. There is almost too much of what they each wrote and said, compared with what they did or the impact they had—if any—on India and Indian ecology, in this book. There are some brief exceptions, however. Like the section on "Gandhian economist" JC Kumarappa who went up against Jawaharlal Nehru to campaign for rural revival in the earliest five-year Plans. (Guha explains how and where most of these thinkers met M.K. Gandhi or were influenced by him, though there isn't a complete chapter on Gandhi's environmentalism in this book.)

Third, there isn't an overarching narrative or takeaway, except to learn about 10 people who thought about human-nature interactions at different points in time, in different parts of the country. Each of the chapters takes a longish biographical route to set up the environmentalist thought of the person in focus. The result is that we see how their individual thinking on nature may have developed in response to their times and experiences, but there isn't that much space left to examine how these thoughts translated into actions (other than writing letters, essays, reports) or impact or even inspiration to future green activists.

Ramachandra Guha at the IIC in Delhi in November 2024. (Image credit: Moneycontrol)

Ramachandra Guha at the IIC in Delhi in November 2024. (Image credit: Moneycontrol)

In a conversation with Moneycontrol, Guha said that the book is not meant to inspire policy or impact on the ground, but to document the thinking of people who "went against the grain", "warned us" about the effects of environmental degradation in the pursuit of industrialization and that perhaps the examples of these 10 people could inspire young Indians today. He also explained some of the thinking behind picking these 10 individuals over others like the famous ornithologist Dr Salim Ali or the architect of the Green Revolution in India M.S. Swaminathan. Edited excerpts from the conversation at the India International Centre, where Guha was staying ahead of the Delhi launch of the book in November 2024:

What do you want people to take away from the book?

It's a work of history, so they should read it for what it tells us about the past, about individuals who had interesting ideas. It is not about their life, it is about their ideas. So, people (featured are those) who worked on forest, wilderness, urban planning, conservation of water, biodiversity and also the importance of social justice in thinking about the environment.

The environment is sometimes misrepresented as an elite concern. It's about beautiful trees and endangered species like the tiger. (It's) not me, but the protagonist of this book, starting with Rabindranath Tagore in the 19th century, argue that care, love, protection of the environment is vital for human survival. And several of them argue—which is evident today in Delhi because of air pollution—that when environmental degradation or environmental abuse takes place, it affects the poor most. It's the working class, the slum dwellers, the commuters who face the cost of a problem that has not been tackled by successive governments.

What I'm trying to show through this book is that there was an array of some very interesting individuals working in India, some Indians, some Western, who warned us against a particular pattern of economic growth that would destroy not just the environment but also human lives. But having said that, this book is about 10 remarkable thinkers.

The work of a historian is to acquaint their readers with something new, interesting, unusual, thought-provoking; but not to advocate, not to prescribe, not to tell them. Unlike other historians, I don't believe that I can offer you or any other reader a lesson. You can draw your own lessons from what you read.

You write that some of these thinkers' ideas were maybe presented to policymakers at the time, but they didn't really pan out in terms of policy.

Yeah, they were present in the public. Sometimes (presented) to policymakers, but generally to the public. Like my writings are also presented to the public.

So, how did you see this: ideas that were presented but didn't actually make an impact...

The job of a historian is not to decide policy. This book is to document thinkers who went against the grain. There was a consensus that India had to follow the European and American model of industrialization, go down certain path. There was a consensus among all our politicians, left wing and right wing, and that remains till today... that environment is a secondary concern and a peripheral concern. It (the point of the book) is to show people who argued otherwise, demonstrated otherwise.

The work of a writer like me is not to prescribe. It is to tell the truth as they see it, and to talk about the dangers of following particular policies. But they are not in politics, they are not godmen, they can't offer miracle cures. They can awaken your consciousness. They can show you things that shall we say, bureaucrats, civil servants, intellectuals who only want to be close to the Prime Minister and hence hide the truth from him and everyone else, will not show.

So, like me, the 10 people in this book are independent writers trying to document how society and nature is changing, and to document that with rigor, with seriousness and honesty.

You write about JC Kumarappa in the book. Now, he went up against Nehru several times and had a different idea of what should and shouldn't be included in the earliest five-year Plans. But let me play the devil's advocate here and ask that if it didn't play out like Kumarappa argued, then what is the point of remembering that history?

Because we still confronting that problem (environmental degradation, and the pitting of conservation against economic progress) in a more acute way, perhaps.

Firstly, the point of remembering is that history is not only about winners. History is not only about kings. It is about ordinary people. History could be about the losers too, you know, because maybe the losers were right. Today, Gandhi may have lost in saying that Muslims and Sikhs and Christians have equal rights apparently. But we know what the neglect of Gandhi's vision will mean for us if we go forward with it, we will become like Bangladesh or Sri Lanka.

Your question presupposes that it is only worth writing about people who are famous, people who are successful, people who are powerful. I will give an example of cricket. Isn't the story of Vinod Kambli as interesting as Sachin Tendulkar? What hurdles did someone from a particular background face? I mean, Sachin Tendulkar is a Brahmin, Vinod Kambli is from a Dalit/OBC caste. Sachin's father is a professor. Vinod Kambli's father is a construction worker. Now, these are all important to understand the diversity of human life. The uncritical celebration of success is itself a problem. I myself have always looked at forgotten stories of unusual people who are interesting, remarkable, courageous, farsighted, independent-minded and may not have succeeded—that's fine. that's fine.

To take forward your analogy of Vinod Kambli and Sachin Tendulkar. That is not a zero-sum game. You could be interested in Vinod Kambli as well as in Sachin Tendulkar. However, in the case of policy, it either happened or it didn't. You can either ban bullock carts on Delhi roads like Nehru did briefly or you can ban cars, which is what Kumarappa suggested as a counter.

No, no, no, not at all, not at all. If you've reflected deeper on Kumarappa's question—Nehru did many remarkable things, which I have written about in other books. Without Nehru, India would not have been united; without Nehru, India would not have been a democracy; without Nehru, Indian Muslim would not have had equal rights; without Nehru, women would not have had equal rights—but Nehru had a blind spot when it came to development. If Nehru or people around Nehru had pondered that question, does a lorry or motor car own the Delhi road or does the bullock cart own the Delhi road?

Supposing you had pondered that question, and you looked around the world as a sensitive economist: Nehru as Prime Minister is all powerful, he thinks he knows everything, and Kumarappa is a troublemaking activist. Could there be a middle ground between them? Could there be a kind of a compromise solution that works its way through the simple juxtaposition of a motor car versus bullock cart? Yes (there is a middle ground). I give take an example: The Delhi Metro system, which should have been begun in 1950, not in 2000. Europe had metros, America didn't. In India unfortunately, from Nehru onwards till today, it's only the motor car, and the motor car is responsible for climate change. Without the motor car, there would be no climate change. The motor car is a terrible thing in terms of its mass use, because of what all it does to the environment.

Someone in the Planning Commission, overhearing this debate between Nehru and Kumarappa, may have said: this Gandhian is a radical naysayer. He wants to live simply. He is living in his village. But (what about) the people who want to come to the city, to commute in Delhi... But should the motorcar have full power to crush the bullock cart? Let's see what Paris is doing, what Moscow is doing, maybe that's a good way of taking people across Delhi, right? This is really good example, if you look back, you will see why the metro was needed. Now fortunately, but belatedly, we are also taking the metro to the other cities. Bangalore is building it. But again, if you look at the debate in Bangalore today... they will say we will build an underground tunnel through the whole of Bangalore. I think this ridiculous juxtaposition actually may force you to think deeply and come up with something which is pragmatic, learning from the activist, learning from someone you think is an extremist, but (someone) who is posing a real question: Is the individual motorcar really a temporary solution or is it a long-term solution for people and for the environment? Actually, that could be something a young reader could take away from this.

My new book, SPEAKING WITH NATURE, releases today. It is available here: https://t.co/RcGrplSgKpand in bookstores. It features ten remarkable individuals who, long before the climate crisis, wrote with passion and insight about environmental sustainability and social justice. pic.twitter.com/zhydyY3Ba1

Ramachandra Guha (@Ram_Guha) October 10, 2024

Why these 10? There could have been a whole chapter on Gandhi or maybe an entire book on Gandhi...

Well, I have written two books on Gandhi which are 1,800 pages combined. I may write about Gandhi later also. I have an epigraph on Gandhi (in this book) which tells you where he stands, and it has two Gandhians: JC Kumarappa and Mirabehn are both Gandhi's close disciples who are taking his ideas forward in the environmental domain. Just as Nehru may have taken it forward in the domain of Hindu-Muslim harmony and Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay may have taken it forward in the domain of women's equality. These two are taking Gandhi's ideas forward in this domain in a more systematic way than Gandhi could do because Gandhi had so much else to do. So that's why I didn't include Gandhi.

Now, I gave a talk in Bangalore when the book was released (in October), about some other people I could have included, for example, Salim Ali. But eventually I decided to include M. Krishnan. The reason: First of all, each of these 10 people are interesting, unusual, remarkable. Each of them are working in different areas: on cities, on farming, on agriculture. They are working in different parts of India. So they cover a wide geographical and ecological range of issues.

Now, I thought of (not including) Dr Salim Ali for various reasons... There could be others, too. (Another person I could have included, but ultimately didin't). There was an irrigation engineer who warned against large dams in river waters in the 1930s and '40s in Bengal. But a book has to be manageable. No book can be definitive. I mean this book is 400 pages now. 'India after Gandhi' is 900 pages long. My two-volume Gandhi biography is 1,800 pages long. Those are not definitive, because there are still things that other people can say (about Gandhi). Every work of history takes a conversation forward, takes our understanding of the past forward. It will spark a debate like the conversation we are having now, like when you write reviews, and then other scholars who are maybe younger than me, more energetic than me will take it still further. So this is the first history of early Indian environmentalists, but it's not the last. There will be a second and a third and a fourth and a fifth. That's true everywhere. 'India After Gandhi' was the first history of post-independence India. But there have been other books since that have taken my argument forward, that have nuanced them, that have suggested that I was mistaken in making, say, this point about the bullock cart and motor cars, right? That is the job of a historian; to carry a conversation further, not to close it. So eventually some principle of inclusion and exclusion will be there and the only way to justify your inclusions, the only way the inclusions will be justified, is if I am able to persuade the reader that these 10 people are interesting, unusual and they are saying things a) that they never heard of, b) they are saying that them in a compelling way, and finally c) what they are saying, how they are saying it, somehow relates to me in 2024, even if they are saying it in 1924.

So that is my hope for this book: it's not the last word and it's not a guide to our present problems. It's a deepening of our understanding of the past and an appreciation of the work of some very remarkable, unusual, neglected individuals.

You've written a book about the Chipko movement earlier—you mention it in the introduction to this book as well. To take a little bit of a leap here, would you say a movement like that could be possible today? If yes, why aren't we seeing more of these?

I think that's a very good question. There are protest going on. It's not like there are no protests against environmental abuse. But the government comes down with a very hard hand. Governments, not just today but for the last 20 years, are much more brutal in suppressing dissent of this kind than the governments of the past. Chipko happened in the early 1970s, the Narmada movement happened 1980s. I was a witness to them both, and demonstrations, dharnas, arguments, debates were possible.

Environmental dissenters are called anti-nationals. I have to say that the media goes along with this narrative. The media has demonized environmentalists in the most awful way across the world. And partly it's just ignorance. They don't understand the complexity of the problem. The young today, and I mean people not just in our large metros but even in our smaller metros, are much more aware of the environmental and social crises that India faces today, than people my generation; we were really totally enchanted by steel mills and large dams and our first nuclear bomb in India.

Apart from the repression, another reason why social movements have become more difficult may be because of that instrument that all of us carry: the smartphone. In the old days, if you wanted to protest peacefully, you had to come to the streets. Now you think you post a picture on Instagram, you sign a petition—it is all important—but these things... nonetheless, given that the young today are much more aware, much more conscious, really gives me some hope. That is something. So how will this awareness translate into social movements, how will it percolate in the corridors of power... that question you raise I can't answer.

Ramachandra Guha (Image credit: Moneycontrol)

Ramachandra Guha (Image credit: Moneycontrol)

Tell us about the research that went into the book. Apart from ecology, you are also coming in from the political economic perspective in a way.

That comes from my training as a historian and sociologist. The research for this book is like the research for any other work... it is based on documents and letters and reports and newspaper accounts spread across many different archives all across the world. Less than 5 percent of the material used here is available on the Internet... It's the private papers of these individuals. It's technical scientific documents that are not easy to get in India, so I travelled abroad, not abroad.

So it is based on materials not in the public domain which have been synthesized and sifted through by me and presented in a way in which... I integrated environment and society. There is economics, there's a little bit of technology, there is caste, there is gender and there is on the other hand the forest, soil, et cetera, et cetera.

Were there any findings that were surprising to you?

Well, I've been working for so long... but some aspects were surprising. For example, Tagore—his environmentalism was so deep, so profound, so multilayered...

But we know that he started Santiniketan

Yeah, but we have a vague idea. We know him more for his poetry, songs. His influencing Gandhi, and we know him for Santiniketan but we don't really understand how much the environment was integrated into his educational philosophy. That Tagore was such a serious and thoughtful environmentalist whose ideas are still relevant was something I vaguely understood, but not (did not fully appreciate) till I started researching.

It is the details. You know, with Patrick Geddes, the town planner. His arguments, his plans were so visible and why they were neglected. Patrick Geddes is really interesting because most environmentally oriented thinkers at that time followed the Gandhian tradition of saying the problems are in the countryside, not in the city. And Geddes was saying no, one day they will be in the city too, because India may currently live largely in the villages but there will come a time when you will become an urban culture, and will have to cope with water, clean air, transportation, energy, housing... And that is the importance of his work.

To repeat what I said, like any work I have written, it's based on extensive research in documentary and private collections where you have to ferret it out stuff and then you of course make sense of it, you present it in a certain way based on your understanding.

Were you tempted to include people like MS Swaminathan and his Green Revolution?

That's a good point. Salim Ali could have been one person who could have been included, and I didn't include him because M. Krishna was more interesting, more diverse. M.S. Swaminathan see, again, the choice would have been between Swaminathan and Albert Howard. But like I said about 15 minutes ago, this book is an intervention and a debate and I hope to take it a few steps further, but other people will take it even further. So one of the hopes I have for every book I write, is that to provoke and inspire younger scholars to write books on aspects that I may have ignored or underplayed.

I have written about 10 individuals. If a young scholar interested in these debates wants to write a whole book on Salim Ali, it would be eminently worth it. Extraordinary figure who, though he only had a BSc, basically become a world-class ornithologist and inspired a whole generation of bird scientists all over India and the world. Who was also played a role in conservation policy; the Bharatpur sanctuary and so on and the Bombay Natural History Society, making it a very important scientific research organization. So whole book on Salim Ali will take this debate further. A whole book on MS Swaminathan will take this debate further. He is a very interesting man. Since you mentioned Swaminathan, I don't mention him by name, but I start the chapter on Albert and Gabrielle Howard by saying that the Green Revolution saved India. That in the 1960s, because of the famine and the scarcities, India was on the brink of starvation. I say that: "Within its own terms the new agricultural strategy was a success. India was now on the way to becoming self-sufficient in food. This economic security would also assure its political independence... By the early 1980s, however, there were visible signs that this economic and political benefit (of the Green Revolution) had come at an ecological cost" and the impact of chemical agriculture and so on.

Now why Swaminathan is very interesting is that he played an important role in the Green Revolution which made India self-sufficient (in food) but then he realized that there were problems with the strategy, and he spent the last two or three decades of his life advocating green villages. That is quite remarkable because normally people—particularly successful, powerful men—don't rethink what brought them success.

Both Swaminathan and Salim Ali deserve really good biographies because they are both extraordinary people. Their thinking was very insightful, but also flawed. And a biography has to be written taking (this into account)—like when I write about Gandhi, I also write about his flaws. Swaminathan died last year and Salim Ali died 37 years ago. So there's a kind of gharana of Swaminathan-influenced scientists and a gharana or Salim Ali-influenced scientist. Not a debunking biography, but both the books would take forward what I am trying to do, and I would love to see them.

You write about the role of the British in scaling up the exploitation of natural resources in the subcontinent. Now, there's been an effort to throw off the colonial yoke for the past 76 years. Why do you think it's so difficult for us to move away from this?

First of all, the British brought in modern industrialization based on high uses of energy and capital and concentration of scale to India. But that same form of industrialization was followed in Germany, in United States, in Russia, in Japan and in China. There is a perception that industrialization along this model makes countries powerful and famous. We have thrown up the British yoke. We are politically free—that's how Nehru and his colleagues or the planners are thinking—but to consolidate this political freedom, we have to beat them at their own game; we have to build larger factories, bigger cities, more fancy cars and so on. And that imitative model was also the model of the Soviet Union which was socialist and not capitalist. But the great Lenin, he greatly admired Henry Ford. He thought, 'Wow, I will do it. But when I do it, it will be better.'

So it's not so much the British per say, but this template of Western industrialization which has just ravished the world. And we can't afford to do it, because our population density is higher, our ecology is more fragile. These (10) thinkers are saying that you have to forge your own path that will work for you. And we, the ruling elite is captive to this fantasy that to beat America or England at their own game, we have to, you know, follow this path.

Can the chapters be read out of the order in which you put them?

Yes, absolutely, absolutely. As long as you read the introduction. Though, of course, there's a certain logic to the way I placed them. One thing I'll say, and this connects to this question and earlier question you posed, when you write about multiple individuals, different readers will find different individuals compelling. I mean I wrote a book on seven foreigners who fought for India's freedom. There again, you have the same thing.

It's not in chronological order...

It starts with Tagore and ends with M Krishnan who died in 1996; so, it is broadly chronological. I don't say this in the book, (but) it starts with three Indians, then it comes to five Westerners who worked in India, and then it ends with two Indians, so there is also that kind of symmetry.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.