Book Extract

Excerpted with permission from the publishers Shattered Lands : Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia Sam Dalrymple, published by Harper Collins India.

*****

Proxy Wars

The 1960s saw the ties that had once linked Arabia to South Asia largely disappear. But in India, Pakistan and Burma, where the new borders crossed land rather than sea, it was not so easy to forget the links that previously united the region.

Throughout their first decade of independence, all three countries had taken much closer trajectories than is often appreciated. Each aspired to democratic socialism, each economy was dominated by military spending and each faced the challenge of rehabilitating the millions displaced in the violent 1940s. All three countries were also keen to avoid being pulled into the global Cold War, receiving arms from the US to battle revolutionary communism, while also preaching socialism and establishing close relations with the USSR and China. In 1955 India, Pakistan and Burma collaborated with Indonesia and Ceylon to organise the Bandung Conference – a grand meeting of Asian and African countries – and promote anti-colonialism and non-alignment on a global scale.

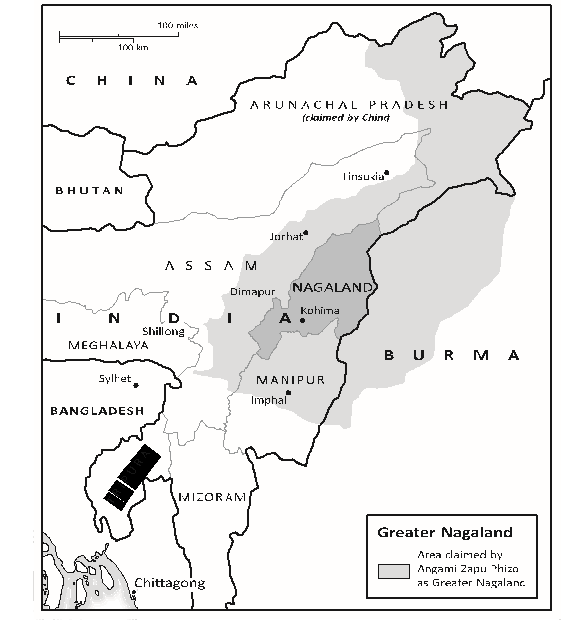

As the 1960s progressed, however, the threat of communist overthrow waned and the tentative alliance between India, Pakistan and Burma started to fall apart.1 Three ethnic communities – the Nagas, the Mizos and the East Bengalis – had been seeking independence from their respective nations for over a decade, and in their attempts to shift the borders of the Radcliffe Line, each would become embroiled in a proxy war between India and Pakistan.

In 1971 the Bengalis of East Pakistan would succeed in forging a new nation state called Bangladesh. But at the start of the 1960s it was the Naga liberation struggle, spearheaded by the half-paralysed former insurance salesman Angami Zapu Phizo, which looked most likely to succeed.

By the 1960s Angami Zapu Phizo was a bitter man, horrified at the way Nagaland had become part of the Indian Union yet nearby Sikkim and Bhutan had escaped merely through their respective monarchs signing protectorate treaties with India after independence. ‘Had Nagaland been a Kingdom,’ he later said, ‘her personality would have been recognised internationally, as happened in case of the tiny Kingdoms of Bhutan and Sikkim, in the further northeast of India.

But Nagaland has always been a land of tribal democracies without the leadership of a single person like a King or a Prince.’ Phizo opposed the moderate line of other Naga politicians, who sought regional autonomy within the Indian Union, and instead lobbied on both sides of the Indo-Burmese border for outright Naga independence. Rustomji, adviser to the governor of Assam, recorded that what struck me about Phizo was his extraordinary thoroughness and pertinacity. He was around with neatly typed, systematically serialised copies of all documents relevant to the Naga problem and he gave the impression of carrying, single-handed, in his little briefcase, the destinies of the Naga people.

In 1951 Phizo set about collecting a range of ‘thumbprints and signatures’, and then publicly announced that 99.99 per cent of Nagas had voted for independence. It remains unclear how this ‘plebiscite’ was carried out and who had taken part, but when Nehru heard the news he considered Phizo’s demands to be an ‘absurd … fairy tale’. Rebuffed by Nehru, Phizo announced the Nagas would perform a Gandhian ‘satyagraha’ and ‘face bullets without retaliation’, if that was what it took to reunite them with the ‘400,000 [Nagas] … on the Burmese side’ of the Patkai Hills.

Indian official Jaipal Singh met the Naga leader afterwards and tried to persuade him against ‘any further fragmentation of India in the form of a new Pakistan’. But Phizo was unmoved, and a journalist who observed the meeting noted ‘the fires of [his] dedicated eyes’.

In 1953 Phizo had crossed into Burma, from where he planned to take his proposals to the United Nations, but a Burmese border police patrol discovered him and detained him in Monywa.10 Indian authorities pressured the Burmese to extend his detention, and Nehru used the opportunity to visit the Naga Hills with U Nu, his Burmese counterpart. The two prime ministers found themselves rebuffed, however, and when they arrived to give a public address, the public simply walked away and ‘bared their bottoms as they went’.

From this point on it was a gradual slide into open Naga rebellion. Upon his release, Phizo formed a parallel government and, in the words of one Indian official, ‘began planning for armed resistance’. By 1954 murders were being reported across the region, targeting both the Indian Army and Naga politicians. This culminated on 22 March 1956, when Phizo formally declared Nagaland an independent state. Moderate Naga leaders who opposed Phizo’s use of violence were found dead in mysterious circumstances.

Most explanations of the Naga revolt view Phizo’s movement through the lens of secessionism but it is perhaps more useful to see it as an attempt to undo the partition of India and Burma and reunite the Nagas on both sides. As his own family members claimed at the time, ‘The Naga revolt against India was due to this accident of geography whereby an ethnic community was slashed into various bits by artificial frontier lines.’

As the administration in the Naga Hills collapsed, an Indian general requested permission to ‘machine-gun hostiles using aircraft’ in the same way the British had during the Quit India protests. Nehru refused, and his army instead took to creating irregular militias of Naga volunteers to suppress Phizo’s movement.15 Nonetheless, it was a watershed: ‘Nowhere else in the country, not even in Kashmir, had the army been sent in to quell a rebellion launched by those who were formally citizens of the state.’16 India, people would soon learn, could be much harsher in crushing rebellions than even her colonial predecessor. On 16 December 1957 Phizo was smuggled to the East Pakistani border, hidden inside a human coffin with one hundred thousand rupees in cash.

‘I remember looking down to the plain covered by a layer of winter mist,’ he later told his biographer. The sun was not yet above the horizon, but I looked on the promise of safety. We waited until cowdust-time, as the people of the plains call dusk, to make the final crossing of the border. Praise God we have survived, I told those with me as we gathered in prayer.

Safely across the border, Phizo and his companions set out for Dacca to meet Pakistan’s defence minister Ayub Khan. With a waxed moustache not unlike the surrealist artist Salvador Dalí’s, Ayub Khan had commanded a battalion in the Assam Regiment before Partition and had worked closely with the Nagas during the Second World War. If anyone in Pakistan was likely to be sympathetic, thought

Phizo, it was him. But the Naga leader was in for a ‘great shock’ when Ayub detained him inside a Dacca police compound and sent ‘astonishingly unreliable intelligence officers’ to interrogate him.19 Phizo probably assumed he was going to be deported back to India or handed to the Indian authorities but instead the intelligence officers tried to persuade him that Assam – including the Naga Hills – rightfully belonged to Pakistan. Pakistan, it seems, was convinced that Indian subterfuge lay behind the political restlessness in East Pakistan and decided to keep hold of Phizo, as a threat. The peace established by Liaquat and Nehru still held, but cooperation was giving way on both sides. Phizo had become a pawn in a much larger struggle. A South Asian cold war was afoot.

**********

Sam Dalrymple Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia Harper Collins India, 2025. Hb. Pp.536

A history of modern South Asia told through five partitions that reshaped it.

As recently as 1928, a vast swathe of Asia--India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal, Bhutan, Yemen, Oman, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait--were bound together under a single imperial banner, an entity known officially as the 'Indian Empire', or more simply as the Raj.

It was the British Empire's crown jewel, a vast dominion stretching from the Red Sea to the jungles of Southeast Asia, home to a quarter of the world's population and encompassing the largest Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Zoroastrian communities on the planet. Its people used the Indian rupee, were issued passports stamped 'Indian Empire', and were guarded by armies garrisoned forts from the Bab el-Mandab to the Himalayas.

And then, in the space of just fifty years, the Indian Empire shattered. Five partitions tore it apart, carving out new nations, redrawing maps, and leaving behind a legacy of war, exile and division.

Shattered Lands, for the first time, presents the whole story of how the Indian Empire was unmade. How a single, sprawling dominion became twelve modern nations. How maps were redrawn in boardrooms and on battlefields, by politicians in London and revolutionaries in Delhi, by kings in remote palaces and soldiers in trenches.

Its legacies include civil wars in Burma and Sri Lanka, ongoing insurgencies in Kashmir, Baluchistan, Northeast India, and the Rohingya genocide. It is a history of ambition and betrayal, of forgotten wars and unlikely alliances, of borders carved with ink and fire. And, above all, it is the story of how the map of modern Asia was made.

Sam Dalrymple's stunning narrative is based on deep archival research, previously untranslated private memoirs, and interviews in English, Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Punjabi, Konyak, Arabic and Burmese. From portraits of the key political players to accounts of those swept up in these wars and mass migrations, Shattered Lands is vivid, compelling, thought-provoking history at its best.

Sam Dalrymple is a Delhi-raised Scottish historian, film-maker and multimedia producer. He graduated from Oxford University as a Persian and Sanskrit scholar. In 2018, he co-founded Project Dastaan, a peace-building initiative that reconnects refugees displaced by the 1947 Partition of India. His debut film, Child of Empire, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2022 and his animated series, Lost Migrations, sold out at the British Film Institute the same year. His work has been published in the New York Times, Spectator and featured in TIME, The New Yorker and The Economist. He is a columnist for Architectural Digest and, in 2025, Travel & Leisure named him ‘Champion of the Travel Narrative'. Shattered Lands is his first book.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.