A little before the sun moved behind the nearest mountain, I turned around. Enough. I cursed myself having realised the dangerous hubris that led me up the wrong path, having earlier taken a wrong left trail instead of the right right. I had started late at 11 am — the 12-odd km and 2,500 ft climb up to Kheerganga, I knew, was a mere day’s hike instead of what beginners and tour operators loftily call a trek. I hadn’t planned well, having had a local villager at Barshaini — where road ends and trail begins past the unappealing and monstrous hydel power plant — draw a rudimentary trail map on a chit. And, into the wilderness, I was walking solo. It’d have been all good had I not lost my way.

At Kheerganga, a rare phenomena taking place in the sky. (Photo: Shamik Bag)

At Kheerganga, a rare phenomena taking place in the sky. (Photo: Shamik Bag)Now while turning back after two hours of tangential walking through a trail that got increasingly shrubbery, blindsided too, by the occasional chocolate wrapper and empty cola bottles strewn around (must be those irresponsible Kheerganga "trekkers"), I hurried. The 9,700ft-high Kheerganga it can’t be in the looming dusk; I'll simply be happy if my headlamp returns me to the starting point, Barshaini, and further, to the hashish-addled, tourist-overrun world I wanted to leave behind in Himachal Pradesh’s Kasol.

Suddenly, in that trailless terrain richly camouflaged by mid-November’s fallen dried leaves, I tumbled, crashing at least 15 ft. Regaining my nerves, I tried crawling up, but fell each time. What’s happening? I rummaged through the leafy carpet to discover loose pebbles and gravel — I had stepped on to a landslide zone. Battered and bruised, and after dreadful minutes of trying, I held on to a steadfast branch of a fallen tree. Sweating, despite high Himachal’s November cold, my parched throat sought water, dry as they were from my yelling for help that never came. Somewhere, during those many tumbles and struggle to crawl up on all fours, the water bottle had fallen off the side perch of my backpack.

Prayer flags at Dzongri, on the way to Goecha La. (Photo: Shamik Bag)

Prayer flags at Dzongri, on the way to Goecha La. (Photo: Shamik Bag)Crawling back on to the trail, and getting cold, dark and desperate, I knew I had to bivouac. Ice melt trickling down between rocks from the upper reaches solved the water crisis; in my backpack I had two packets of Parle-G biscuits, dates and a compact sleeping bag; my pocket held a lighter. Water, food and fire sorted, my headlamp ferreted for a giant rock or a formidable tree trunk to protect my back during the emergency nightover in the mountainous forest. But then, I shuddered — almost every other local person I met earlier had a bear story to tell. Realising that my lithe frame or my meagre resources will be no match to a curious onrushing bear in the Himalayan dark, I dropped the idea of the bivouac and slowly trudged along in the twilight that felt ominously laden with unforeseeable dangers.

Darkness, though, has its benefits. In this case, it made the lights of Barshaini’s hydel power plant light up the distant horizon in a faint orange glow. The world of neon that I wanted to escape from was now my lodestar. I knew which way to head. But at a bend, suddenly a crashing sound of branches from the slopes above. I hid behind a tree, expecting the greedy bear to appear after all. The crashing sound again, intermittently. Impatient and fatalistic, I slowly crept up the bend and looked up fearfully — bang in the middle of the throw of my headlamp, with a sickle in hand working at cutting branches, stood an elderly Himachali man. Equally agape on seeing me, the man, who could have been god-sent to me, asked incredulously, “Arre, yahan kahan gaya (Where did you go)?” The taut tension releasing off me, I could only think of saying in my halting Hindi, “Kho gaya.” I got lost.

And therein lies the story — between the going, losing and finding one’s way is the nut graf of man’s foray into the wild.

Almost nothing explains this delicate equation better than high-altitude trekking.

Where the motorable road ends is the point from where one treads into oneself for trekking is as much about wandering into the mind as it is about exploring unknown physical heights. At any rate, it feeds into our unrest; at best, it exposes human fragility and vulnerability against the extremities of nature. One returns frost-bitten, calloused, hardened and often, wizened from the experience.

It is also a walk away from the inanities of our modern digitised lives, for trekking, in its true sense, also begins from where the radiating range of mobile cellular towers ends, thereby leaving behind the allure of banal Instagram Reels and Facebook Stories, digital marketplaces and free credit card deals. Trekking can make your mobile phone redundant, except, perhaps, for the use of its camera to freeze earth’s pristine reality. In the way, trekking — barring over-trampled routes like the Annapurna and Everest base camps in Nepal — is not hostage to shop-and-dine experiences and mass tourism’s many consumerist trappings, it is both archaic and anarchic.

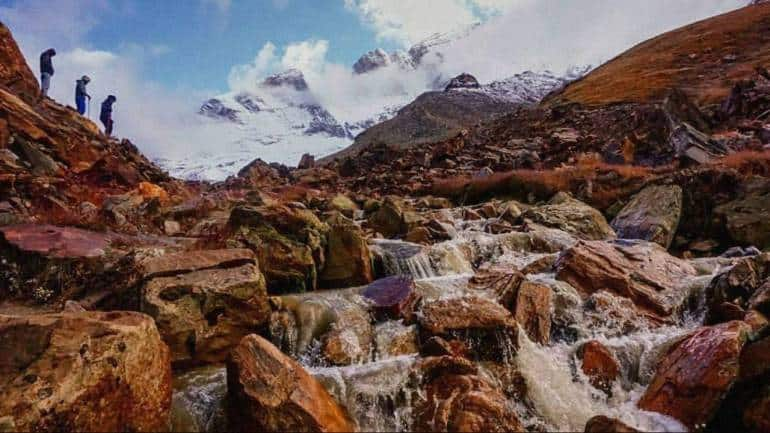

On the Kedar Tal trek, cloud mountain and snow melt water. (Photo: Shamik Bag)

On the Kedar Tal trek, cloud mountain and snow melt water. (Photo: Shamik Bag)The up-and-down and down-and-up of high-altitude trekking, a team member told me during a particularly strenuous 11-day trekking expedition to Sikkim’s 16,210 ft Goecha La at the foot of the world’s third-highest peak, Mount Khangchendzonga (aka Kangchenjunga), approximates the crests and troughs, fall and rise of life itself; the walk through relatively even valleys and plateaus reflecting life at a steady clip. Every gasp, every deep breath, every pounding of the heart on a near vertical incline could be conduit to a reintroduction with the self. Trekking, I’ve always felt, is about journeying in.

Near Goecha La, at a sub-zero balcony-like ledge near the bottom of the 21,950 ft Mount Pandim facing the unblemished, blinding whiteness of the Khangchendzonga, our ears suddenly buzzed with a tremendous grim sound rushing down while the ground beneath vibrated. We looked up the Pandim’s slope to make sure if the unseen avalanche was hurtling down towards us and our certain deaths. No, it was a safe distance away on the Khangchendzonga. On another occasion, from Sandakhpu, West Bengal’s highest point in the Darjeeling hills, we saw the first rays of the sun trigger the first plume off the Khangchendzonga summit. These pure moments of sound, rage, fury and beauty I would later come to recognise as a certain stillness in motion.

Near the Chaukhamba, during the Madhmaheshwar trek. (Photo: Shamik Bag)

Near the Chaukhamba, during the Madhmaheshwar trek. (Photo: Shamik Bag)While on the short but prodigiously steep climb from the tortuously beautiful Chopta village in Uttarakhand’s Garhwal to the Tungnath Temple and Chandrashila Peak at 12,110 ft, a senior priest of the temple attested to the philosophical stasis that one often encounters while on the move over high Himalayan trails. As I sat at a nook overlooking deep gorges leading to spectacular peaks, panting from the rigorous climb, the septuagenarian priest, deep creases on his forehead lined with sandalwood paste, trudged slowly up, a brawny horse following his every step. He was going up to the temple. I wondered why not on the horse. As long as he can, he’ll walk, the priest declared; the horse being there only when his legs give up. After all, it is an animal like us, the priest reasoned.

Up at the windswept Chandrashila summit, hundreds of framed photos of people young and old, plastic garlands, diyas and camphor sticks lay around, left behind by relatives of the deceased. It is a spot from where prayers of the bereaved travel afar. The photo frames, mostly cracked and misshapen in shape, it is said, go under the snow in winter only to resurface with the melting summer heat. In that eerie zone of spectral beauty my eyes travelled across the gorges to the mammoth icy wall of the Chaukhambha — the 23,419 ft peak where, amid the constant torrents of snow, storms and unforgiving churn of the elements, lay the undiscovered bodies of two mountaineers from Kolkata I knew through their trekker wives. Stillness within motion.

Near the Chaukhamba. (Photo: Shamik Bag)

Near the Chaukhamba. (Photo: Shamik Bag)Back on the Kheerganga route, I found a home. The elderly Himachali gentleman, who identified himself simply as Negi, would hear nothing of my attempt to go back to Barshaini. I had to stay back with him that night. We walked up to his log hut in the middle of the mountain. After a dal-roti dinner, along with fresh warm milk from his cows, Negi gave me his room and slept in the barn with his cattle. “Family room,” he laughed while countering my protests.

This was a week into November 8, 2016’s demonetisation move of the Indian government, which overnight invalidated Indian currency notes of high value, of which the farmer who lived off his land, had no clue of. Neither his son, who lived and worked in the plains, nor the news, had travelled up. I implored him to somehow get the repudiated Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes exchanged at the nearest bank. He laughed heartily before showing me his savings kept inside a small tin box in the kitchen: only a handful of hundred rupee notes were bundled within. All legal tender, still.

The Khangchendzonga plume. (Photo: Shamik Bag)

The Khangchendzonga plume. (Photo: Shamik Bag)I stayed back the next day and helped him water his apple trees and collect fodder for the cattle and dried branches for his fire. The following day, he led me to the correct Kheerganga trail. We sat together on a rock and took a photograph using the timer on my SLR camera. His eyes welled up when we hugged before I left. Inside his embrace, there was the warmth of home.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.