Last month, museums in France, Spain, and other countries organized special events to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death. Many people were less than enthused. For them, Picasso doesn’t need celebration because his raging misogyny offsets his achievements as an artist.

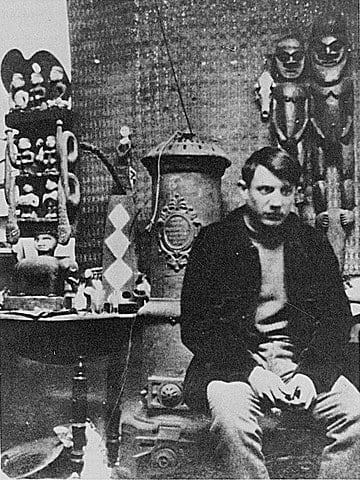

Pablo Picasso in 1908 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Pablo Picasso in 1908 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On the other hand, take Louis-Ferdinand Céline, an egregious anti-Semite. Philip Roth openly admitted to being influenced by the French writer’s exuberant style, going so far as to call him his Proust, “even if his anti-Semitism made him an abject, intolerable person”.

Picasso and Céline are hardly the only creative figures to be pilloried. Directors from Woody Allen to Roman Polanski, musicians from R. Kelly to Michael Jackson, and writers from Hemingway to Bukowski have all been accused of forms of abuse. Some have even been convicted.

Abuse apart, there are many instances of artists with execrable opinions. Philip Larkin held bigoted attitudes. T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf expressed anti-Semitic views. Morrissey and Eric Clapton delivered racist rants.

Should their work be shunned? Two recent books address this issue: Erich Hatala Matthes’s Drawing the Line and Claire Dederer’s Monsters. Matthes, a philosophy professor, takes a reasoned approach, and Dederer, a writer and critic, explores her thoughts in a series of personal essays.

As a starting point, Matthes writes, one could ask whether the moral failings of artists make their artworks worse. It’s worth keeping in mind that “moral complexity is part of what makes art so irresistible” by challenging accepted views and offering alternative perspectives.

An important consideration is whether the art condones or reflects troublesome predilections. (Those who can’t stand Woody Allen often mention that his Manhattan features a 42-year-old writer dating a 17-year-old girl.)

However, sorting artists into saintly and sinister and then assuming that their character will influence their art leads to a dead end. “We need to explain why what an artist expresses in their work must be linked with specifically good or bad aspects of their character,” he writes. Unpicking these strands can be impossible.

All the same, especially at a time of the Me-Too movement and cancel culture, “carrying on as if nothing has changed can seem like a way of ignoring victims”. We need to navigate the gap between what the art means to us and our knowledge of the actions of its creator.

Such ambivalence can be a virtue. It forces us to critically examine the effect of art on our lives, which is far better than moral grandstanding. As “ethical art consumers,” we make our own judgements rather than take a stand because it seems like the right thing to do.

While racist, misogynistic, and homophobic views should certainly be objected to, Matthes emphasizes that it’s an institutional response, not an individual one, that can make a difference. “It’s easy enough for those in positions of power in the art world to acquiesce to the cancelling of some representative artists,” he writes, “without making any significant alterations to who wields power in their organisations or how decisions are made”.

In other words, even when cancel culture chooses the right target, the bigger picture is ignored. The point is to build systems that offer accountability to help prevent future abuse.

Ultimately, Matthes concludes, it’s irrelevant whether we can or should separate the art from the artist. He urges us to engage deeply with the work instead. This can clarify conflicted feelings: you could still find the work compelling, or you could loathe the artist with “nostalgia for a work that once inspired but now repulses you”.

This subjective slant informs Claire Dederer’s Monsters, a series of interlinked essays. The book grew out of an earlier piece in The Paris Review which posed the question: what do we do with the art of monstrous men?

Re-watching films by Woody Allen and Roman Polanski, she says: “I wished someone would invent an online calculator [to] assess the heinousness of the crime versus the greatness of the art and spit out a verdict: you could or could not consume the work of this artist.” If only it was so simple.

Her book unpacks the question of separating the creator from the creation by delving into her own past life and work, and recounting discussions with friends and others. It’s part-memoir, part-investigation.

Dederer is unconvinced by critics who promote disinterested assessments. “Authority says the work shall remain untouched by the life… Authority sides with the male maker against the audience.” Such criticism believes in the myth of objectivity “unshaped by feeling, emotion, subjectivity”. In the real world, we are governed by emotion “around which we arrange language”.

Among her useful concepts is that of the stain: a dark aspect of an artist’s life that spreads to colour their work. “When someone says we ought to separate the art from the artist, they’re saying: remove the stain. Let the work be unstained. But that’s not how stains work.” This is also why we can recoil from work created long before an artist’s reviled act.

Our expectations of how artists should behave have given them much leeway. Dederer explores the shop-worn myth of the genius which owes much to Picasso and Hemingway, characters who were “muscular, unfettered, womanising, virile, cruel, sexual”.

To constrain their actions, some have felt, would be to constrain their art. Instead, “we reward this bad behaviour until it becomes synonymous with greatness”. Thankfully, such attitudes are coming under increasing scrutiny.

Not all of Dederer’s essays have the same impact; there’s a sense of straining to expand her original piece into a book-length work. Passages on Nabokov’s Lolita or Sylvia Plath, for example, add little to the debate.

Elsewhere, she ventures into the potentially interesting zone of whether women can be seen as “art monsters”. She notes that some, like Doris Lessing, have been chastised for abandoning their children in pursuit of their work. These and other examples expose sexist attitudes, but hardly fall into the same camp as the others discussed.

Why do people have such extreme reactions nowadays? For Matthes, the artists we love “embody certain ideals that attract us to them”. As fans, our attachment forms part of our identities and reveals something about who we are and what we aspire to. A betrayal of trust runs deep.

Dederer also explores this phenomenon. The result of living in “a biographical moment” is that knowledge about celebrities makes us feel we know them intimately. In an Internet age, this leaves us vulnerable in unfamiliar ways. “No wonder we don’t know how to behave in this new landscape, or even how to feel.” The result: fan obsession and its dark shadow, cancel culture.

Both emphasize a response born of thoughtful engagement. While Matthes points to the role of institutions, Dederer highlights a deeper systemic concern. “In late-stage capitalism,” she writes, individual choice becomes “irreparably soldered to consumer choice”. Ethical gestures are meaningless because they create the illusion of control which “makes us more trapped in the spectacle”.

Now, there’s a lot to be said for investigating how capitalism turns us into collaborators. However, introducing this notion at the tail-end of a book seems unwarranted, if not unearned.

Most flawed people – artists or otherwise – deserve empathy because at some level, we’re all works in progress. Ultimately, the decision whether to engage with their work or not should be personal, not universal. Much depends on the nature of the transgressions, the art, and our feelings. It’s clarity, not certainty, that’s worth striving for.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.