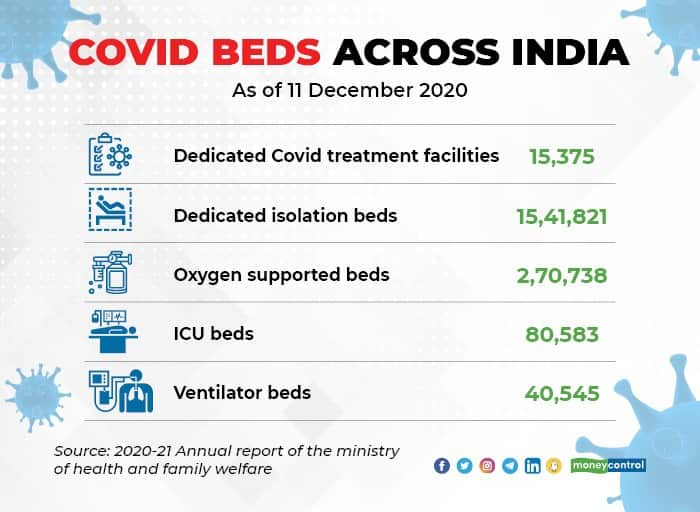

As the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic was ebbing late last year, India had a little more than 1.5 million isolation beds across 15,375 dedicated treatment facilities for a population of 1.38 billion. That translates to a skosh over 1 bed per 1,000 people. Just 18% of these were oxygen supported beds, according to the 2020-21 annual report of the ministry of health and family welfare.

Each of these dedicated facilities had about 5.2 intensive care unit (ICU) beds on average. In all, there were a total of 80,583 ICU beds for Covid patients, and about half of these were ventilator beds. These numbers were no doubt small yet seemed adequate as the transmission of the virus was relatively slow.

Shortage Exposed By Pandemic

As the number of cases continued to decline in January 2021 and the number of patients requiring hospitalisation fell, many of these dedicated Covid facilities were discontinued or closed down. Among the ones discontinued were the 10,000-bed facility at the campus of Radha Saomi Satsang Beas in Chhattarpur, near the Delhi-Haryana border and the 1,000-bed facility run by the Defence Research and Development Organisation in Delhi Cantonment. Both ceased operations in February.

Ergo, when the country was ravaged by an aggressive second wave this March-April, there were fewer beds for Covid patients, not just in Delhi, which has been under the spotlight for the misery that people were forced to endure, but also in many other parts of the country including Mumbai. The virus has now made its way into the rural areas, where healthcare infrastructure is mostly rudimentary, hospital beds short and the nearest ICU bed at least a few hours away. The toll might be heavy if the virus moves unhindered deeper into rural India.

The Crisis in Delhi

Delhi has taken some corrective steps in the past few days; the number of hospital beds has increased as more private hospitals were drafted as Covid hospitals and the two temporary facilities re-opened. Yet, the demand for beds, and especially ICU beds, continues to outstrip supply.

Oxygen, oxygen cylinders and concentrators continue to be in shortage, although the acute crisis has been addressed. Hospitals are crippled by a shortage of doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers, and that has taken its toll.

Beds in some prestigious public hospitals such as the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and Ram Manohar Lohia continue to be inaccessible to the masses as they are said to be reserved for politicians, bureaucrats, members of the judiciary, other well-connected people and their families.

Mumbai has fared better on adding Covid care beds. It has also flattened the curve after a few weeks of struggle, aided by the lockdown.

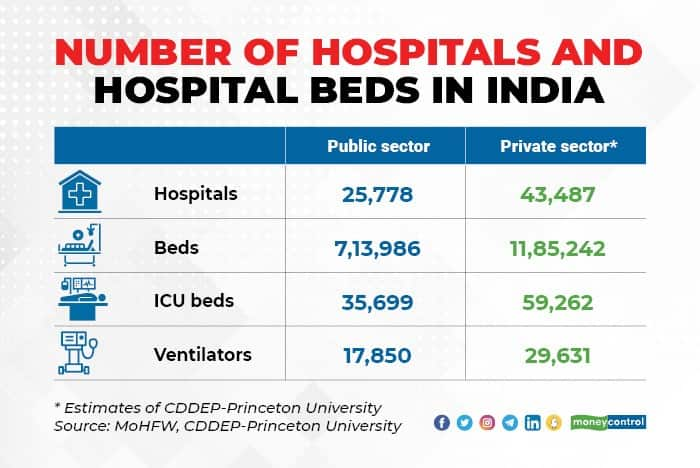

The second wave of the pandemic has once again exposed the inadequacy and unpreparedness of India’s healthcare infrastructure to deal with pandemics. India had just about 7,13,986 hospital beds across 25,778 hospitals in the government sector before the pandemic began, the health and family welfare ministry estimates.

The number does not include beds in the primary healthcare centres, most of which are in rural areas and are used to address more routine health problems. It must be stated here that the health ministry has been lax in updating the data on hospital and beds in the government sector. The data on hospitals and hospital beds has not been updated since December 2018 for several states and since December 2015 in a few instances such as Delhi, Karnataka and West Bengal.

Worse, there are no accurate estimates of the number of hospital beds available in the private sector. The Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy (CDDEP), an independent think tank, and Princeton University had estimated that number at 43,487 hospitals and 1,185,242 beds in a study in April 2020. This might be an underestimation, given the proliferation of nursing homes and small-to-medium sized hospitals across the country.

However, if the estimates of the health ministry and CDDEP-Princeton University are taken as accurate, India had just about 13.76 beds per 10,000 people when the country was hit by the first wave of the Covid-19 infection. In the government sector, it was just about 5.2 beds per 10,000 people. The study has estimated the total number of hospitals at 69,265 hospitals with 1,899,228 beds across the country. Not all these hospitals were available to Covid patients during the first wave or now.

Critical care beds are scarce. Of the estimated hospital beds in the country, just about 5% were placed in the intensive care units. Just about half of the ICU beds were attached to ventilators. The health ministry estimated that there were about 35,700 ICU beds in the government hospitals of which 17,850 were ventilator beds.

That translates to about 25.87 ICU beds per one million people in the government sector. That’s woefully short given that ICU beds in the private sector are beyond the means of a sizeable proportion of the population. The CDDEP-Princeton University estimated the number of ICU beds in the private sector at about 59,260. Thus, the public and the private sector together have about 68.8 ICU beds per one million people.

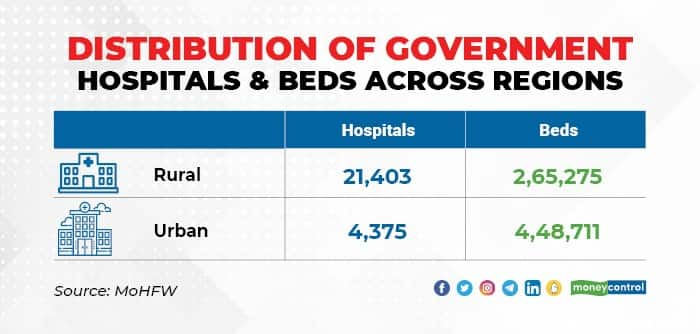

The uneven spread of hospitals and beds is another problem that people have to deal with. Though a larger proportion of government hospitals are in rural areas, urban areas have a larger share of beds. The government hospitals in rural areas are small and have 12.4 beds on average compared to 102.6 beds in the hospitals in urban areas.

This is also a pointer to under-investment in hospitals in rural areas, which forces people to travel long distances to find treatment even for diseases that should ideally be treated locally. City hospitals are better equipped with diagnostics, laboratories, life-saving equipment, doctors and specialists.

There is also a disparity in the spread of public hospitals across states, and that’s an outcome of the priorities of successive state governments. India’s most populous state Uttar Pradesh has the largest number of hospitals but had fewer hospital beds than less populous states such as West Bengal and Tamil Nadu. Likewise, Bihar had just about as many beds as a far less populous Haryana and Assam had about 50% more beds than these two states. Kerala had far more beds than much Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

The pandemic has underscored the need to urgently invest in the public sector healthcare infrastructure. The current wave of the pandemic is set to extract a huge toll due to the inadequacies of the healthcare infrastructure.

There might be a third wave in the not too distant future. However, urgent measures taken now by the Union and state governments to upgrade the quality of healthcare infrastructure and hospital care can limit the damage inflicted by it.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.