A few days ago, I was startled by the headline of a news report that popped up on my Twitter feed, that Johnny Depp would be directing a biopic called “Modi”. I clicked on the link and learnt that the planned film is on the life of the great early 20th-century painter Amedeo Modigliani, called “Modi” by his friends.

I am a huge fan of Modigliani’s art and have framed prints of two of his paintings on the walls of my home. His style is original and distinctive, portraits with elongated faces with no pupils in the eyes—when asked by one of his subjects, he said: “I'll paint your eyes when I see your soul.” And the story of his short tragic life—he died in 1920 of tubercular meningitis when he was only 35—is fascinating in a very morbid way.

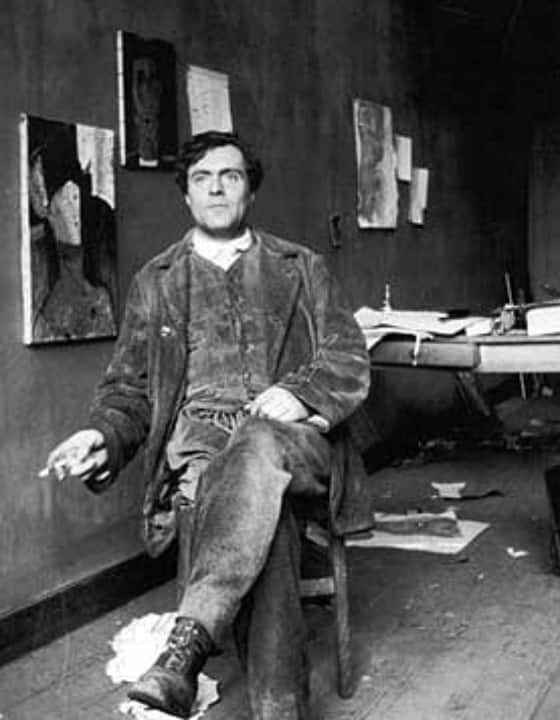

Amedeo Modigliani (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Amedeo Modigliani (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

An alcoholic and drug addict, he spent most of his adult life on the edge of utter penury. He could manage to have only one solo exhibition of his work in his lifetime and gave away many of his paintings to get meals at restaurants. In 2018, his Nu Couche (Reclining Nude) was sold for $157.2 million at a Sotheby’s auction.

His love life was wild—he fathered at least four children, all out of wedlock. In the last years of his life, he may have found stability with Jeanne Hebuterne, a young woman who was renounced by her devout Christian family for her relationship. They planned to marry, but then he died. The day after Modigliani passed away, Hebuterne, who was eight-months pregnant, jumped out of a fifth-floor window, killing herself and the unborn child.

It is of course pure coincidence, but Modigliani shares his name—Amedeo—with another bad-boy creative genius, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. “Amedeo” is the Italian derivation of the Latin “amadeus”, which means “beloved of God”.

Modigliani and Mozart are hardly alone among great creators in their reckless debauchery and defiance of societal norms of their times. Some years ago, my daughter introduced me to the paintings of the late 16th and early 17th-century Italian painter Caravaggio (real name: Michelangelo Merisi). Caravaggio was not only a stunning talent; he practically invented much of art as we know it today.

He painted Biblical themes, but represented the characters as contemporary people wearing contemporary clothes. For his models, he hired common people off the streets, often beggars and destitutes. This was an enormous philosophical move away from the European masters, including Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who painted classically good-looking people. Caravaggio’s Bible paintings are visceral and sometimes bloody; the Christian icons in his works are often shown as filthy and malnourished—an “unsettling realism”, to quote the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

He also transformed the way the light and the dark are depicted by painters. Using deep shadows and brilliant light, he brought a striking vividness to his portrayals. Most great European painters who came after him, from Rembrandt and Vermeer to the Impressionists, would be influenced by him.

Caravaggio's Judith and Holophernes Toulouse (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Caravaggio's Judith and Holophernes Toulouse (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

But the kindest way to describe Caravaggio as a person is to say that he was a thug. A violent drunk who got into fights all the time, he was convicted of murder, and spent the last years of his life as a fugitive from justice. He died, lonely and penniless, at the age of 38. Like Mozart, he was buried in an unmarked grave.

The life stories of these astonishingly talented people raise an obvious question: Is there any connection at all between art and the “morality” of the creator? Because many of the greatest creative people in history were certainly not nice people and brought nothing but grief to those who loved them.

Also read: Can you love the art but hate the artist?

The diaries of Leo Tolstoy, author of War and Peace and Anna Karenina, reveal that he was often driven mad by uncontrollable sexual desire—“Must have a woman”, “Terrible lust amounting to physical illness”, he wrote. He contracted venereal diseases and infected his wife. Picasso, compulsively promiscuous, destroyed the lives of several of his lovers. Dylan Thomas, one of the greatest British poets of the 20th century (“Do not go gentle into that good night/ Rage, rage against the dying of the light”) spent much of his adult life lying to friends to get some money out of them so that he could buy a few more drinks.

Victor Hugo, who enjoys demi-god status in his native France, preyed on his housemaids. Thomas Malory, who wrote Le Morte d’Arthur, which gave the world the stories of King Arthur and the knights of the round table, was what we in India call a “history sheeter”, who spent years in prison for theft, attempted murder and rape.

So should we bring our knowledge of what an artist or a writer was as a human being to bear on their work? The simple answer is: No. Art is a thing in itself and separate from the artist. In fact, art has neither any obligation to follow prevalent moral codes nor any need to have a “purpose”—betterment of society or whatever.

The creator is of course free to have a purpose, but he should also be free to not have any. Charles Dickens wrote many of his novels to expose the injustices and inequities in 19th century England, but more than 150 years later, the sheer pleasure that a reader gets when reading The Pickwick Papers or Great Expectations has nothing to do with Dickens’ reformist motives. This is what differentiates literature, which transcends geographies and time, from pamphleteering.

Robert M. Pirsig was a famously reclusive American philosopher who wrote only two books, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Lila: An Inquiry into Morals. Both straddled the divide between fiction and non-fiction and were huge international bestsellers. In Lila, Pirsig offers an interesting theory: “What’s at issue here isn’t just a clash of society and biology but a clash between two entirely different codes of morals in which society is the middle term. You have a society-vs-biology code of morals and you have an intellect-vs-society code of morals.” He suggests that the creative mind is not bound by rules of society that maintain peace and prevent chaos. After all, creativity, by definition, is about breaking rules.

What if the creators, like the ones I have mentioned, hurt innocent people? They should certainly be judged for their acts. But their works should be judged only for their quality and nothing else. Modigliani and Caravaggio may have led pathetic lives that sowed destruction all around them, but that has nothing to do with their paintings. They are wondrous things and have their own lives.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.