A hero doesn’t become a hero in a vacuum, does he? What is he without a compelling villain? That the world went to see Shah Rukh Khan in Pathaan and came out praising John Abraham as well goes to show Abraham strove hard to build his package. A ribbed body and action scenes aside, dialoguebaazi with the SRK was going to be a Gargantuan challenge. In Hindi cinema, more than the action scenes, it is the protagonist-antagonist dialoguebaazi, the nok-jhonk (repartee) that rings the loudest in a dark hall. And so, to essay Jim with conviction, Abraham rung up actor-cum-dialogue coach Vikas Kumar, with whom he’d previously worked in Parmanu: The Story of Pokhran (2018) and Satyameva Jayate (2018).

“I first met John during Parmanu, on which we were co-actors. For Pathaan, a lot of the work happened during the pandemic, so all the workshops had to be done on Zoom. John as Jim has a lot to speak in Pathaan. Our workshops helped him learn those lines by going over them repeatedly,” says Vikas Kumar, 45. The film got shot over different schedules, so, they had to work a few days ahead of every schedule, on the scenes that were to follow.

“There’s nothing really wrong with John’s Hindi, but, yes, like with many who are from Mumbai, the nasal sounds need some extra work. Since there’s a lot of dialoguebaazi in Pathaan, we had to explore different, most effective ways of saying those dialogues, of course, leaving enough scope for the director to make changes,” Kumar adds, “Sample this, ‘Thode daane zameen pe phenko, cheentiyaan apne aap chali aayengi. Ek bank account yahaan, ek SIM card wahaan…aur yeh raha, Pathaan himself’ or, ‘Jo patte milte hain unhi se baazi khelni padti hai…aur iss baazi mein saare ikke mere haath mein hain’. We would practise saying these lines with different pauses and stresses, changing the intonation, even the mood. There was always a choice between John playing Jim either absolutely cold or being cheeky and having fun. The attempt was to find a balance in different scenes.”

“With dialogues like these, there is always the temptation to sound ‘impactful’, but in attempting to do so, you risk ‘underlining’ too much or sounding very ‘promo’ like. On the other hand, in making it sound ‘natural’ or ‘conversational’, you may just lose the ‘punch’. My suggestion to John was to always keep in mind his backstory — Jim has the most plausible one in Pathaan. What Jim had suffered gave him enough justification to be vindictive towards his own people. If John didn’t play the ‘villain’, and entered every scene keeping in mind why he was doing what he was doing, there would be absolute conviction in his lines, no matter how he uttered them,” he says.

Abraham's practice sessions, however, were far from menacing. “John generally is very good at ‘innocent face’ comedy. He’s charming and funny at the same time. When he’d do Jim’s heavy-duty lines like that, he’d actually sound hilarious,” Kumar chuckles, recalling how on some days, he’d be Pathaan, and on other days, he’d be Rubai, and it would be “great fun to stare into John’s eyes (albeit over Zoom) and say, much like Pathaan does in the film, 'Tere liye ek chheh foot ka gaddha khod rakha hai. Uss mein letne ka position hai. Khud chalega ya ghaseet ke le jaoon?'”

The days of iconic character-defining dialogues with an afterlife might be passé. Think Hum jahan khade hote hain, line wahin se shuru hoti hai (Kaalia, 1981) or Kitne aadmi thhe? (Sholay, 1975) or Mogambo khush hua (Mr. India, 1987). The days of actors and villains speaking spasht (clear), if not shuddh (pure), bhasha (language) might be gone, too. But over the last decade, dialogue-coaching seems to becoming serious business in Bollywood. And Vikas Kumar’s Strictly Speaking is steering that ship, since 2008, with a core team comprising Film and Television Institute of India and National School of Drama alumni.

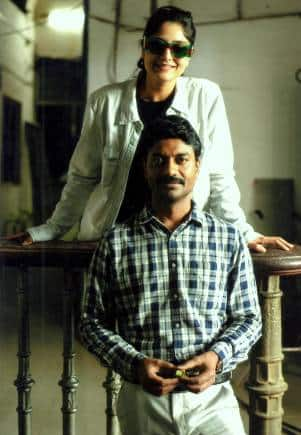

Vikas Kumar's ACP Khan with Sushmita Sen on the sets of the web-series 'Aarya'.

Vikas Kumar's ACP Khan with Sushmita Sen on the sets of the web-series 'Aarya'.

Kumar is better known to the world as ACP Khan from that Sushmita Sen-starrer popular web-series Aarya (Ram Madhvani Films), whose Season 3 arrives later this year. Casting directors have, for the longest time, copped out from casting Kumar in a role other than that of police personnel. CID, Powder, Khotey Sikkey, Ajji, Aarya — good cop, bad cop, he’s played them all. Besides a dialogue-coaching company, Kumar the actor also runs an indie films’ production company.

The boy from Bihar Sharif, in Nalanda district, about 70km away from Patna, had no precedent to follow, but many followed suit after him, giving his example to their parents, “if Vinay babu’s son can go to Bambai, why can’t we?” For him, the road to Bombay came via Barry John’s acting school, Imago, then in Noida. In the “expensive” Mumbai, “almost every TV associate found me ‘unfit’ for their serial. Anyway, I stuck on. And, organically started dialogue-coaching. That kept me busy and my kitchen-fire burning. Eventually, Powder happened,” says Kumar, 45, who’s been coaching the stars in Yash Raj Films' (YRF) movies but hasn’t acted in one YRF movie yet. He’s appeared in their TV series, though, Powder, and as the lead in Khotey Sikkey. And as destiny would have it, Kumar, who once said no to a dialogue-coaching gig on an SRK film because his hands were full only to find them empty in a few months, has today worked on another SRK film, a blockbuster at that.

His first project as a dialogue coach was on a Hollywood film, One Night with The King (2006), starring stalwarts like Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif. Since it was shot in Rajasthan with 40-odd actors from Mumbai, Kumar was tasked to ensure they didn’t sound “too Indian”. “I was told I had to ‘help with the dialogues’. Only when I landed on the set in Jodhpur was I given this badge that read: ‘Dialogue Coach’. Until then, none of us had even heard of the term,” he says.

There was a time in the Hindi film industry, when dialogue-coaching would have been an alien concept. Not only for the likes of Amitabh Bachchan and Shashi Kapoor, for whom Hindi may have been what was spoken at home, but equally adept were actors whose mother tongue was not Hindi, such as Amol Palekar and Jaya Bhaduri. “I think it has to do with your ‘roots’. These actors were all very ‘rooted’. They ‘belonged’ to a certain community or region, spoke their mother tongue. All actors seemed proficient in Hindi and Urdu, and dialogues in most films were spoken in Hindustani. I did try to research but am not aware if there were designated ‘dialogue coaches’ earlier. If there was ever a need for one, I guess writers stepped in. Bandit Queen (1994) is one film that used Bundelkhandi. I’m told a couple of people (including Tigmanshu Dhulia) from the crew chipped in. It obviously helps to have trained theatre actors, with enough exposure to different cultures, on the set,” adds Kumar.

Dialogue coaching has become more common over the last decade and a half, he says. He attributes one reason to the rising number of stories being based in India’s heartlands, “you’d need actors to give, at least, some sense of belonging to the region the film is set in, and for the entire cast to sound uniform. Makers, too, want their films to look and sound authentic, even as they cater to a Pan-India audience. Dangal, Tanu Weds Manu, Vikram Vedha, Ishqiya are a few examples.”

“Then there are actors who are from abroad, who need to work on their diction and the Hindi language. And many newcomers whose first language is not Hindi, who communicate in English at home. They need to shed that ‘angrezipan’ (Anglicism) in their Hindi. Or those with ‘mother-tongue influence’. For instance, a boy from Bihar would have a hard time using nuqtas,” adds Kumar.

A dialogue coach, essentially, works with an actor’s voice and speech to help him/her effectively communicate as the character s/he is playing. “If we narrow down the definition, a dialect coach helps with nuances of a specific dialect, say, add a regional ‘flavour’ (Bhopali in Ishqiya). A language coach would help with a whole new language (teaching Hindi to Malaysian actress Yeo Yann Yann in Vishal Bhardwaj’s segment Mumbai Dragon in the anthology Modern Love Mumbai, or to Alexandr Dyachenko in 7 Khoon Maaf). A diction coach would help with clarity or neutralising an accent (Katrina’s in Phone Bhoot, Kalki’s in Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara). There’s also a voice coach and a speech coach, though these terms come into use more when I’m working with sports commentators, news reporters or with beauty-pageant contestants. In the film industry, these terms are used interchangeably. On a film project, I end up helping with speaking and giving suggestions on dialogue delivery, too.”

The earning could range from, say, “Rs 1,000 for a workshop to Rs 15,000 or more, depending on the scale of the project, time and scope of work, who’s paying — an individual or a production house?” “Unfortunately, many working in film production do not really consider dialogue-coaching a specialist’s job or even that it’s important to an actor’s performance…though they are slowly coming around.”

Apart from Strictly Speaking, “I’m not aware of any other ‘company’ doing dialogue-coaching. There are a few individuals who work independently. I had started solo, too,” adds Kumar, who coaches in Hindi, English and basic Urdu, and his company has specialists in Kashmiri, Tamil, Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Punjabi, Haryanvi, Brijbhaasha, Bengali, Marathi. “When there’s a requirement outside of our scope, we facilitate, find the right person. For Pashto in Bard of Blood (2019), we zeroed in on a boy from Kabul.”

Among the stars he’s coached, Kumar counts Vidya Balan (Ishqiya, Shakuntala Devi), Katrina Kaif (Zero, Tiger Zinda Hai, Phone Bhoot), Kalki Koechlin (ZNMD), Naseeruddin Shah, Arshad, Adil Hussain (Ishqiya), Radhika Madan (Modern Love), Saif Ali Khan, Arjun Kapoor and Jacqueline Fernandez (Bhoot Police), Prithviraj Sukumaran (Aurangzeb), Dulquer Salmaan (The Zoya Factor).

“Ishqiya was my first full-blown Hindi film as dialogue coach. While I didn’t need to think twice when checking Vidya or Arshad or Adil Husain, I’d have had to be extremely cautious with Naseer saab. Because of his stature and how we can get in awe of him. Before a retake, he’d be in the mood of the scene or going over his lines but I’d to approach and check him for Bhopali dialect: ‘Sir, 'aise' nahin 'ese' (Sir, not the Hindi intonation for 'this way' but the Bhopali one)’, and I did that for two months of the shoot! I learnt a lot of tact and found a balance on when I should approach actors and when I should just let them be,” he says.

Kumar has had to coach actors at the oddest of places, too, from Vidya Balan’s car, as she was headed to a meeting, to a salon as Kalki Koechlin got her hair done for the Spain schedule of ZNMD.

There were times when Kumar had to stand his ground. For Tiger Zinda Hai’s dubbing, where Kumar and Katrina Kaif met for the first time, Kumar made a suggestion about saying the dialogue in a particular way, Katrina told him to only check for her pronunciation, not tell her how to say the dialogue. But over two sessions and a couple of days, Katrina insisted he read her lines to show her how it sounds best. “If you’re confident of your skill — and you really can’t fake it — then there’s no need to feel intimidated. Of course, you should put your point across in the right manner.” “I share a healthy working relationship with Katrina. If you’ve noticed her last few outings, I think her Hindi has improved,” adds Kumar, who’s currently coaching Telugu star Samantha Ruth Prabhu for Citadel and will start training Malayalam star Prithviraj Sukumaran on a Dharma Productions project.

Kumar’s own mother tongue is Magadhi, “but at home, we would mostly speak in Hindi with a spattering and lilt of Magadhi. With relatives or in our home village, we would switch fully to Magadhi.” “People tend to use ‘Bihari’ as a general term for the way people from Bihar speak,” he rues, adding, “You can’t expect everyone to know that there are, at least, four languages spoken there. In films, however, a character needs to ‘sound’ like he belongs to Bihar. The lilt or the usage of ‘hum’ instead of ‘main’ becomes more important than getting into hardcore Magadhi or Bhojpuri or Maithili,” says Kumar, who’d score high in Hindi and the Welham school choir would ensure he got the sounds right. Later, his theatre days would make him aware of the Urdu sounds.

So, as a Hindi language/diction coach what does he have to say about the imposition of Hindi as a national language? “As a country, we should celebrate our diversity. Not many people know or understand that Hindi is not our national language. It’s wrong to impose it on people. It’s only done by vested political interests to polarise (people) for electoral gains.”

It is not just in the language, Hindustani, which makes up our Hindi films, the syncretic ethos is what Kumar has grown up amid in Bihar, and that reflects in his indie-film production house, too. Khan and Kumar Media Pvt. Ltd is a collaboration between two school friends, Sharib Khan, a tech-entrepreneur in New York, and Kumar, who grew up on a regular dose of cinema. The company was launched in 2016, their first production began in 2019. Cinematographer Savita Singh’s debut directorial, Sonsi (Shadow Bird), which won the National Award for Cinematography (Non-Feature section) and qualified for the 2022 Academy Awards.

Vikas Kumar with co-actor Saloni Batra on the sets of Ashish Pant-directed independent film 'Uljhan/The Knot'.

Vikas Kumar with co-actor Saloni Batra on the sets of Ashish Pant-directed independent film 'Uljhan/The Knot'.

“Our projects are varied. Right now, we are producing short films (Born to See in English; Shera in Kumaoni) and documentaries (Die Before You Die; Har Saal Ki Bhaanti; Go Gary),” says Kumar, who was first seen in a Vikramaditya Motwane-edited short Shanu Taxi (2006), and has learnt from independent filmmakers Devashish Makhija (Ajji), Ashish Pant (Uljhan) and Aijaz Khan (Hamid), the latter he considers “an extremely important film in my career”, as for web-series, besides Aarya 3 (Disney+ Hotstar), he’s bullish about Kaala Paani (Posham Pa Pictures for Netflix). And, no, he doesn’t play a cop in that.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.