In a scene from Zee5’s Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai, a senior counsel for the accused tells an irate client: “It happens sometimes. I’m not god.” It’s a statement that de-romanticizes the image of the lawyer as a person capable of shaping destiny. Lawyers are nothing but interpreters, people who make sense of a map, as opposed to imposing upon us a new geography of life. For in the context of a judicial case, the letter of the law exists already and exacts a kind of literature to follow and uphold. Lawyers merely make sense of it, by poeticizing what can be and what can’t. But in a country perennially pained by the crawling pace of its judicial systems and crippling historic baggage, the lawyer is everything from hero to prophet and cunning manipulator of fate.

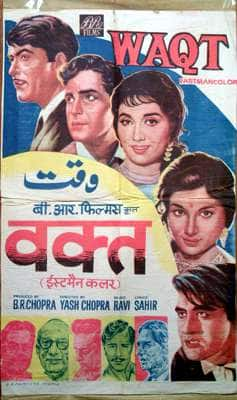

Also read: Manoj Bajpayee: ‘Our job as actors is to find life’s complexities and portray them’Early portrayals of lawyers show truth-seeking individuals carving for the country a moral centre. It’s the kind of naivety that a young independent India expectedly emerged from. From Sunil Dutt in Waqt, to a young Nargis in Awaara, lawyers fought battles to do right by people in the shadow of infantile, yet-to-be-corrupted systems. The judiciary’s infallibility isn’t even a consideration here because courtrooms are temples. No prayer or provocation goes unanswered and it’s a streak that continued until the emergency – that historic deathblow to the very idea of institutional autonomy.

(Image via Wikimedia Commons)

(Image via Wikimedia Commons)In Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh (1980), Naseeruddin Shah plays a lawyer who discovers the conceit that systemic oppression perpetrates in the name of wide access to justice. The courts here are merely places where historic wrongs go to be stripped of their guises. By this point, the post-emergency disillusionment had set in, with writers contemplating what justice even meant if it could not accommodate intuition and empathy. Almost a decade later, Sunny Deol’s washed-up, disillusioned Govind roared his scream of disapproval. “Tariq pe Tariq” became a synonym for just how casually, and imperceptibly, India had drifted off from its intended path. The days of heady moralism gave way to disgruntled lawyers questioning the rulebooks they worked with and under.

via GIPHYThe dreamy '90s obscured much of the country’s courtroom struggles as social and political issues made way for wanton fantasies about love, sex and carnal jeopardy. Not until Jolly LLB in 2013, did we return to courtroom in full, with the lawyer transported to the hinterland, his small-town dreams of making it big, a convenient detour from his usual moral composure. He would do anything to become like the city folk up until, as is common to Hindi cinema, he has an epiphany. Lawyers have since the emergence of cable television news become fairly high-profile celebrities, cultural axioms of everything that is good and bad about our judiciary. At their worst they are everywhere, making victory signs to the press and cornering media bytes by saying mundane things. At their best, they are invisible, quietly dragging one of the many crores of unheard cases, past some sort of finish line. In Pink, for example, a retired lawman returns to fight one last case for women who can use the help.

Also read: Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai review: Manoj Bajpayee is magnificent in this raw, harrowing tale of justiceFollowing a protagonist who must deal with the concept of right and wrong on a daily basis makes for a thrilling moral puzzle. In Disney+Hotstar’s Criminal Justice, Pankaj Tripathi plays a sweet, soft-mannered man of quirky means, who likes a challenge. In Amazon Prime’s Guilty Minds, young, restless lawyers chase cases with the intention of boosting their social status. In the latter, episodic cases continually shift the line of virtue, blurring and rewriting it with each passing moment. Lawyers also make for an unvarnished front row seat to the many things that ail a societal setup – from gendered prejudice to crony corruption. Furthermore, in a country of a billion people, it’s hard to make people care for ‘a’ death. It’s probably where lawyers must also become poets; argue in death for the sanctity of that which isn’t guaranteed in life – equality.

Southern cinema has produced its own thoughtful portrayals of lawyers of late. Tamil Cinema’s usual excesses were sidestepped in the relatively sombre but moving Jai Bhim. Suriya plays the role of a dogged lawyer attempting to get marginalized tribals justice. There is a hint of the upper-caste saviour complex here but none of it eats into the drama and emotion. Typical of its whimsy, Malayalam cinema has assigned lawyers trickier assignments. In Vaashi, a practicing couple lose themselves to arguing competing sides of the same case. In mischievous and thrilling Mukundan Unni Associates, a down-on-his-luck lawyer learns to cravenly invent some of his own. It’s roguish but also, weirdly, life-affirming.

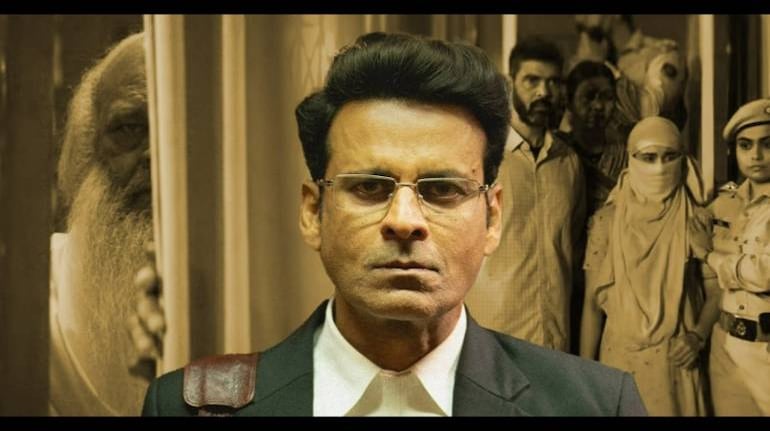

Courtroom dramas won’t ever go out of vogue because to a country stifled by procedural red-tape, the fast-tracked catharsis of cinematic summaries always feels like relief. Manoj Bajpayee’s portrayal of P.C. Solanki, the small-town lawyer who stood up to a Godman and his cult of followers, is flawed but also ultimately rescued by the maverick performance of the actor. He is awkward, scared and at certain points, emphatically human. Bajpayee’s turn is somewhat hampered by his straight-faced righteousness, but it does, through fear and vulnerability, still nudge the needle. This version of the lawyer is without the charisma of a Bachchan (Pink) or the unyielding body language of an Arshad Warsi (Jolly LLB). He wants to win, but without the cost of having to pay for the fight. In some sense, it might just echo the times.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.